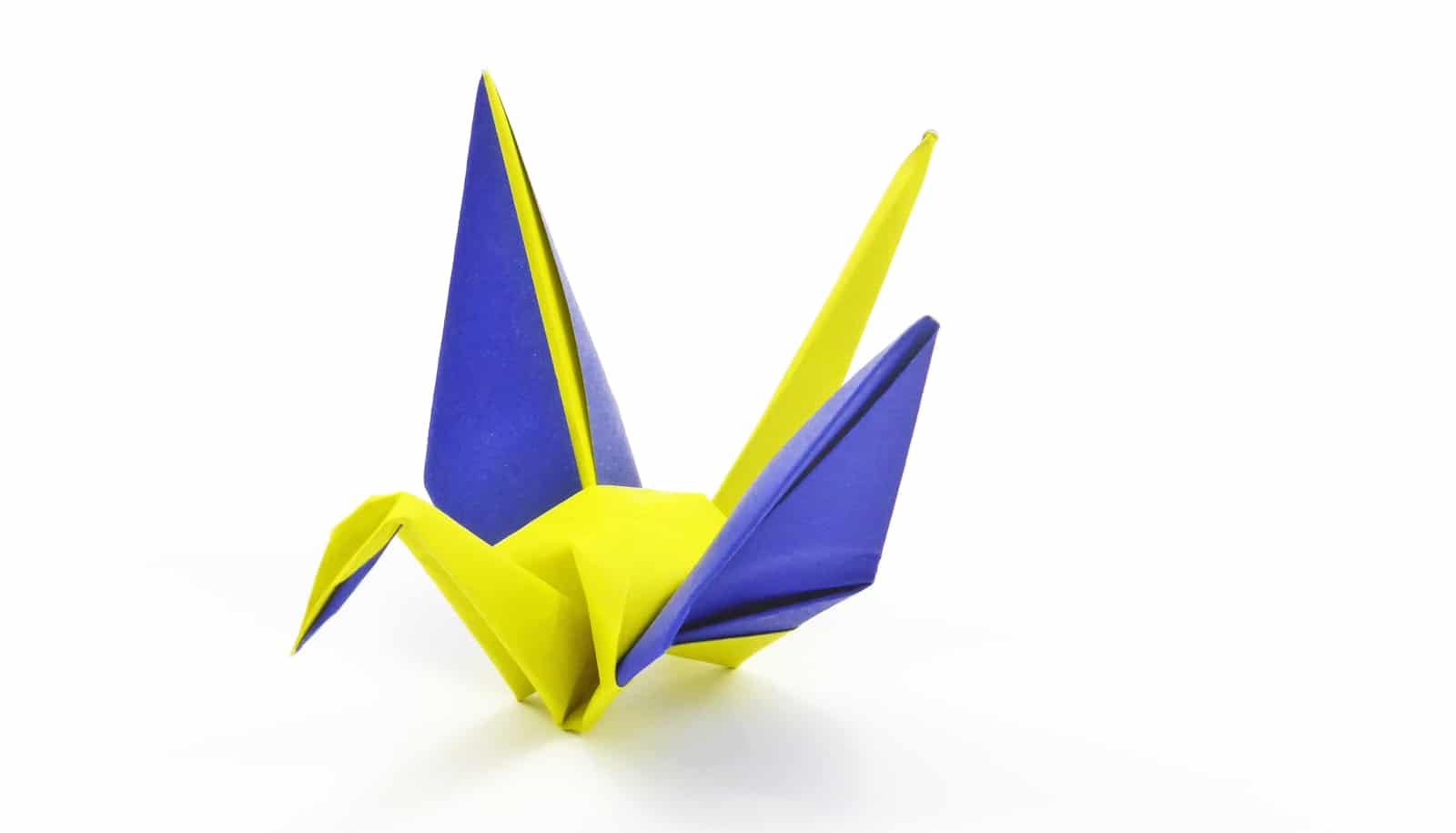

A micromachine that resembles a tiny origami bird flaps its wings and bends its neck as if by magic.

Researchers assembled the micromachine from materials that contain small nanomagnets. They can program these nanomagnets to assume a particular magnetic orientation. When the programmed nanomagnets are then exposed to a magnetic field, specific forces act on them. If these magnets are located in flexible components, the forces acting on them cause the components to move.

For the construction of the microrobot, the researchers fabricated arrays of cobalt magnets on thin sheets of silicon nitride. The bird constructed from this material could then perform various movements, such as flapping, hovering, turning, or side-slipping. The researchers report the work in the journal Nature.

(Credit: PSI/ETH Zurich via GIPHY)

“The movements performed by the microrobot take place within milliseconds,” says Laura Heyderman, head of the Laboratory for Multiscale Materials Experiments at Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) and professor for mesoscopic systems at ETH Zurich.

“But programming of the nanomagnets only takes a few nanoseconds. This makes it possible to program the different movements one after the other. This means that the tiny microbird can first flap its wings, then slip to the side and afterwards flap again. “If needed, the bird could also hover in between,” says Heyderman.

This novel concept is an important step towards micro- and nanorobots that not only store information to give a particular action, but also can be reprogrammed to carry out different tasks.

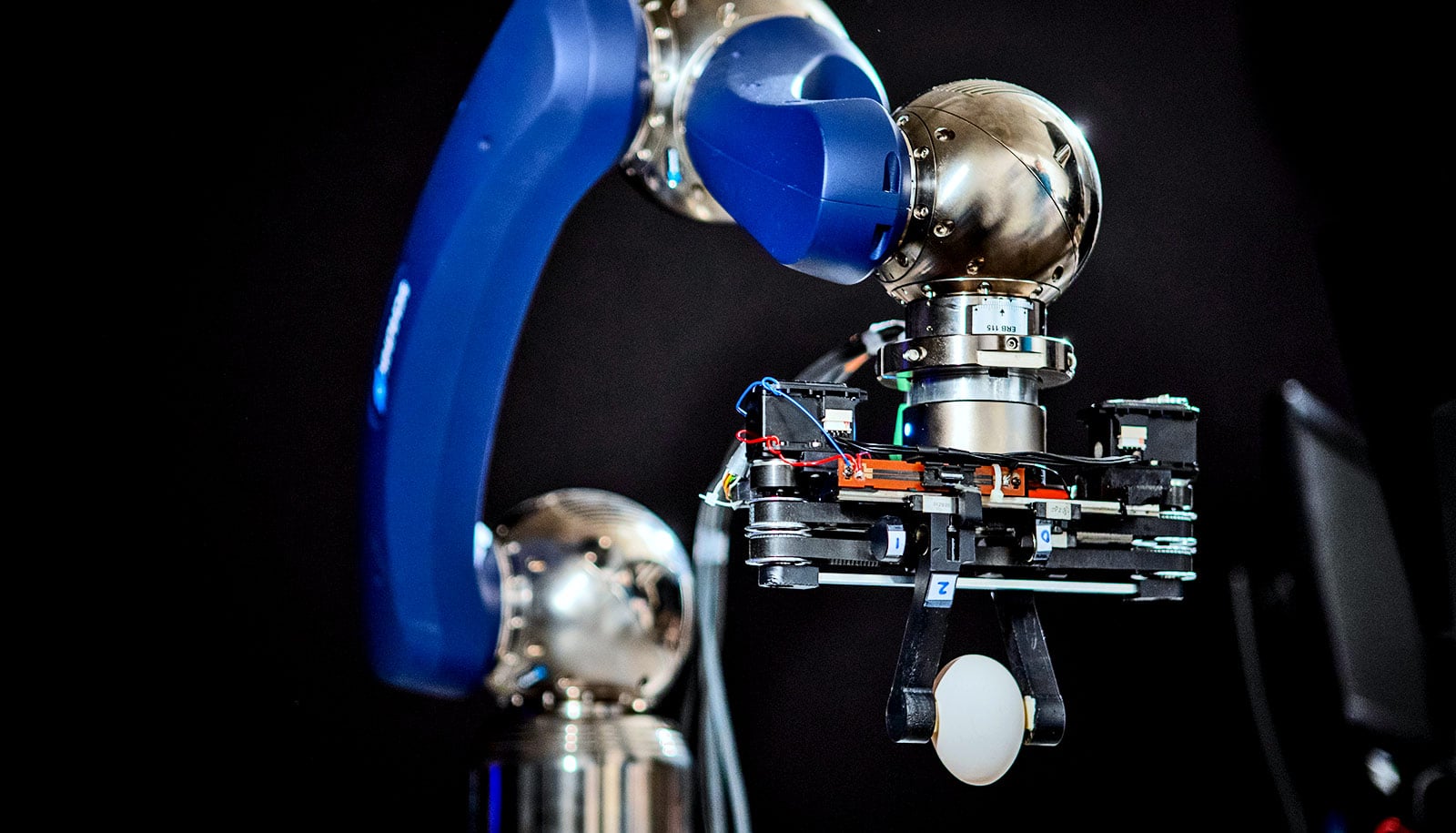

“It is conceivable that, in the future, an autonomous micromachine will navigate through human blood vessels and perform biomedical tasks such as killing cancer cells,” explains Bradley Nelson of the Institute of Robotics and Intelligent Systems at ETH Zurich. Other application areas are also conceivable, such as flexible microelectronics or microlenses that change their optical properties.

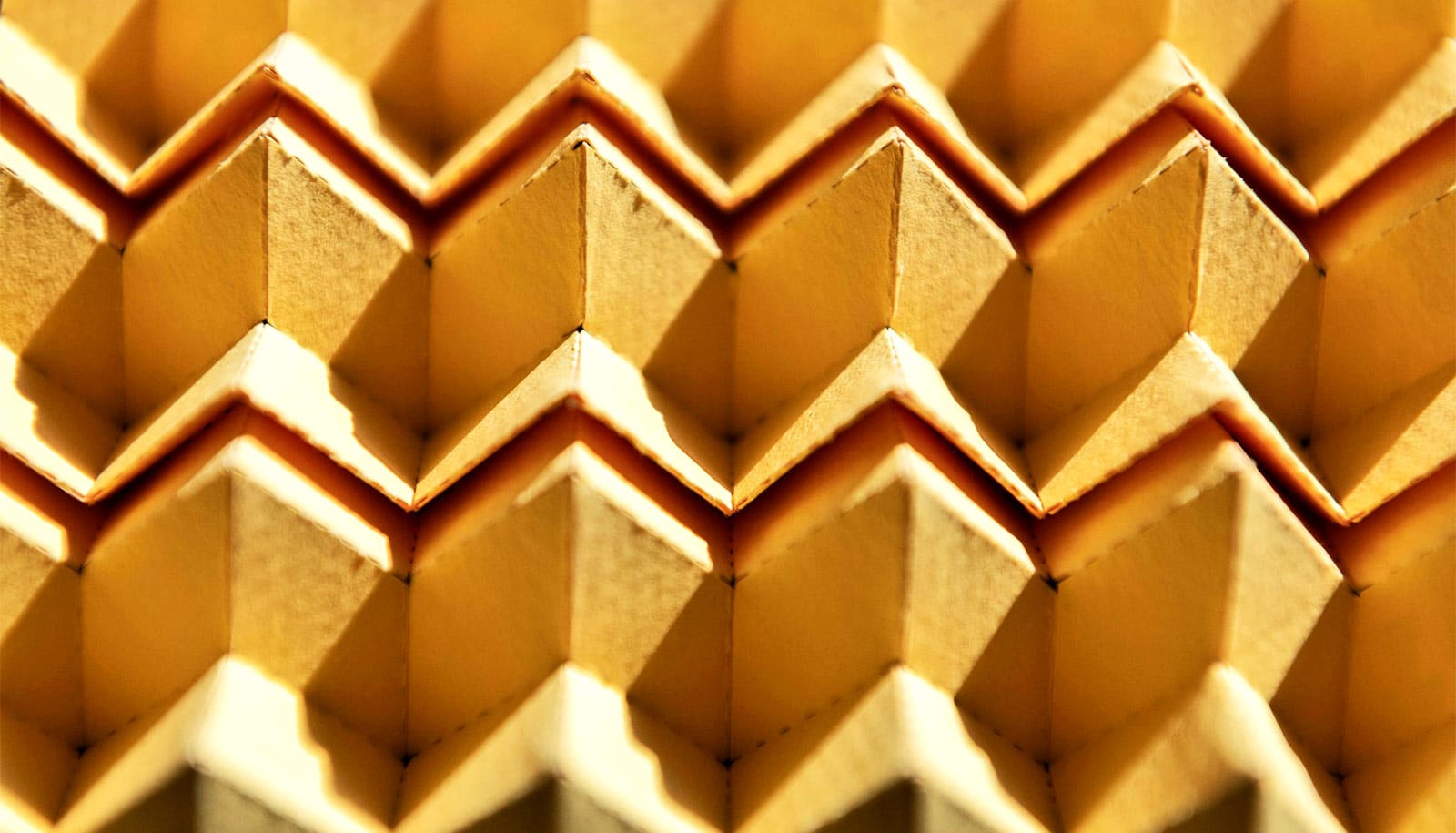

In addition, applications are possible in which the characteristics of surfaces change. “For example, they could be used to create surfaces that can either be wetted by water or repel water,” says Jizhai Cui, an engineer and researcher in the Mesoscopic Systems Lab.

Source: ETH Zurich via PSI