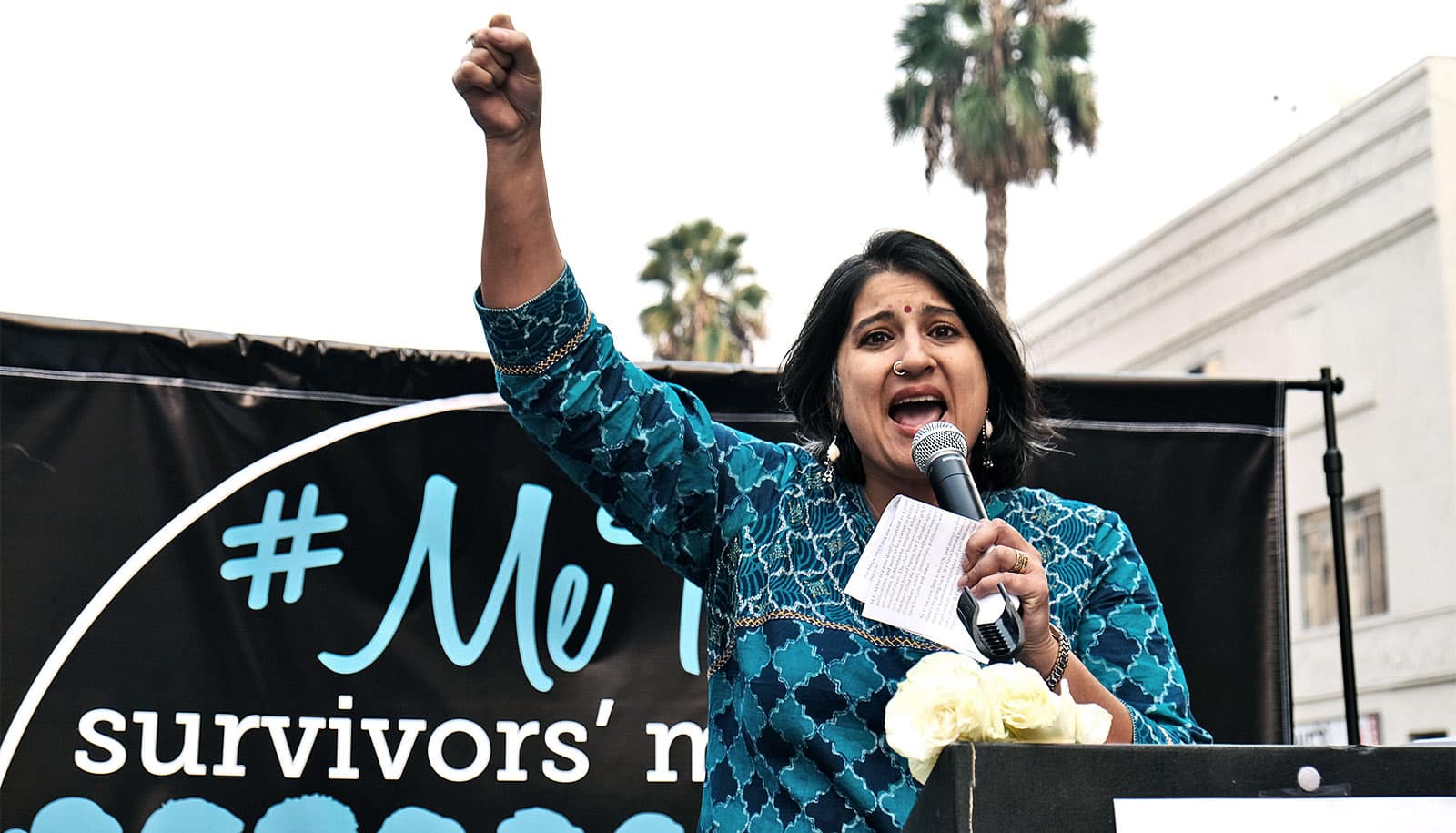

Media coverage of the #MeToo movement often portrays accusers as sympathetic, but with less power and agency than their alleged perpetrators, according to new research.

The #MeToo movement has encouraged women to share their personal stories of sexual harassment. “The goal of the movement is to empower women, but according to our computational analysis that’s not what’s happening in news stories,” says coauthor Yulia Tsvetkov, assistant professor in the School of Computer Science’s Language Technologies Institute at Carnegie Mellon University.

Tsvetkov’s research team used natural language processing (NLP) techniques to analyze online media coverage of #MeToo narratives that included 27,602 articles in 1,576 outlets. In their study, they also looked at how different media outlets portrayed perpetrators, and considered the role of third-party actors in news stories.

“Bias can be unconscious, veiled, and hidden in a seemingly positive narrative,” Tsvetkov says. “Such subtle forms of biased language can be much harder to detect and to date we have no systematic way of identifying them automatically. The goal of our research was to provide tools to analyze such biased framing.”

#MeToo and the media

Their work draws insights from social psychology research, and looks at the dynamics of power, agency, and sentiment, which is a measurement of sympathy. The researchers analyzed verbs to understand their meaning, and put them into context to discern their connotation. Take, for instance, the verb “deserves.” In the sentence “The boy deserves praise,” the verb takes on a very different meaning than in the context of “The boy deserves to be punished.”

“We were inspired by previous work that looked at the meaning of verbs in individual sentences,” Tsvetkov says. “Our analysis incorporates context.” This method allowed her team to consider much longer chunks of text, and to analyze narrative.

The researchers developed ways to generate scores for words in context, and mapped out the power, sentiment, and agency of each actor within a news story. Their results show that the media consistently presents men as powerful, even after sexual harassment allegations. Tsvetkov says this threatens to undermine the goals of the #MeToo movement, which is often characterized as “empowerment through empathy.”

The team’s analysis also shows that the people portrayed with the most positive sentiment in #MeToo stories were those not directly involved with allegations, like activists, journalists, or celebrities commenting on the movement, such as Oprah Winfrey.

The researchers presented a supplementary paper extending the analysis last month at the Association of Computational Linguistics conference. This paper proposes different methods for measuring power, agency, and sentiment, and analyzes the portrayals of characters in movie plots, as well as prominent members of society in general newspaper articles.

One of the consistent trends detected in both papers is that women are portrayed as less powerful than men. This was evident in an analysis of the 2016 Forbes list of most powerful people. In news stories from myriad outlets about women and men who ranked similarly, men were consistently described as being more powerful.

Shaping the narrative

“These methodologies can extend beyond just people,” Tsvetkov says. “You could look at narratives around countries, if they are described as powerful and sympathetic, or unfriendly, and compare that with reactions on social media to understand the language of manipulation, and how people actually express their personal opinions as a consequence of different narratives.”

Tsvetkov says she hopes this work will raise awareness of the importance of media framing. “Journalists can choose which narratives to highlight in order to promote certain portrayals of people,” she says.

“They can encourage or undermine movements like #MeToo. We also hope that the tools we developed will be useful to social and political scientists, to analyze narratives about people and abstract entities such as markets and countries, and to improve our understanding of the media landscape by analyzing large volumes of texts.”

Source: Carnegie Mellon University