Deep in an underwater cave in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, researchers have discovered cave-adapted organisms existing off of methane gas and the bacteria near it.

The discovery raises the possibility that other life forms are also living this way in similar caves around the world.

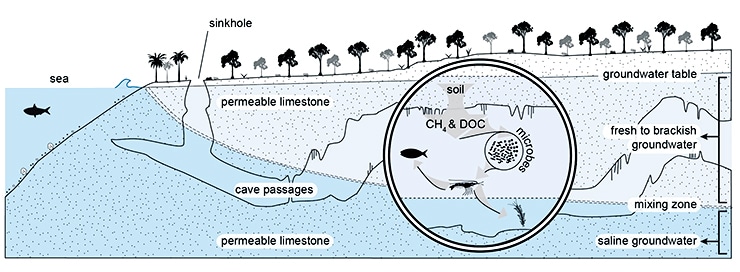

The team examined flooded cave passages within the Ox Bel Ha cave network in the Yucatán where there is a mix of fresh and salt water. Methane in such caves tends to form naturally from surface vegetation and migrates through the limestone in deep waters of the cave network. They found that the methane gases in the area are an important food source for bacteria and other microbes that form the basis of the entire cave ecosystem.

The microbes consume both the methane in the water and other dissolved organic material produced in the overlying soils and permeable carbonate rock, and they form the basis of a food web that ranges from other tiny organisms to fairly large shrimp.

“Methane is the key—the cave organisms have to live off the methane gas, which caught us by surprise,” explains David Brankovits, a graduate student from Budapest, Hungary, who led the research for his PhD at Texas A&M University-Galveston.

“In the studied system, cave-adapted organisms exist where there is no sunlight and virtually all food sources are present in dissolved forms. Without the presence of microbes that can utilize methane and other dissolved energy sources, these animals could not live otherwise. Previous studies had shown that food came from vegetation or other materials in the forest that washed into the caves, but we found very little of that type of debris,” Brankovits explains.

Similar coastal cave ecosystems exist around the world. Brankovits says the next step is to do more research in similar cave systems found in the Bahamas, the Dominican Republic, and other Caribbean locations.

“There are other dissolved organic materials like natural acids and alcohols, down there that we are just now learning about, and we need to explore them in more detail. The results could be surprising,” he notes.

Team member Tom Iliffe, a professor of marine biology at Texas A&M-Galveston, adds, “Providing a model for the basic function of this globally-distributed ecosystem is an important contribution to coastal groundwater ecology and establishes a baseline for evaluating how sea level rise, seaside touristic development, and other stressors will impact the viability of these lightless, food-poor systems.”

Fuel cell microbes turn methane into electricity

The researchers report their findings in the journal Nature Communications.

Brankovits worked with researchers from Mexico, the Netherlands, Switzerland, the University of Alaska-Fairbanks, and the US Geological Survey. The TAMU-CONACYT program, the US Geological Survey, and Moody Gardens Aquarium in Galveston funded and supported the research.

Source: Texas A&M University