Researchers have created a “stealth bomber” virus that could slip past body’s defenses without detection to destroy cancer.

Researchers have discussed and tested oncolytic viruses, or viruses that preferentially kill cancer cells, for decades. The FDA approved an oncolytic virus against melanoma in 2015. But against metastatic cancers, they’ve always faced an overwhelming barrier: the human immune system, which quickly captures viruses injected into the blood and sends them to the liver, the body’s garbage disposal.

Researchers have now circumvented that barrier. They’ve re-engineered human adenovirus, so parts of the innate immune system can’t easily catch the virus. This makes it possible to inject the virus into the blood without arousing a massive inflammatory reaction.

Researchers report their findings of a cryo-electron microscopy structure of the re-engineered virus and the virus’s ability to eliminate disseminated tumors in mice in Science Translational Medicine.

“We think it will be possible to deliver our modified virus systemically at doses high enough to suppress tumor growth—without triggering life-threatening toxicities,” says lead author Dmitry Shayakhmetov, professor of medicine and pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine and a member of Lowance Center for Human Immunology and Emory Vaccine Center.

Shayakhmetov recalls the 1999 death of Jesse Gelsinger, a volunteer in a gene therapy clinical trial who died of cytokine storm and multi-organ failure connected with high doses of an adenovirus vector delivered into the bloodstream.

He says that event inspired him to retool adenovirus, so that it would not set off a strong inflammatory reaction. He views the re-engineered adenovirus as a platform technology, which can be adapted and customized for many types of cancer.

“This is a new avenue for treatment of metastatic cancers,” Shayakhmetov says. “You can arm it with genes and proteins that stimulate immunity to cancer, and you can assemble the capsid, a shell of the virus, like you’re putting in Lego blocks.”

Shayakhmetov started working on the modified virus technology while he was at the University of Washington and founded a company, AdCure Bio, to bring a potentially life-saving therapy to patients with metastatic disease. Other oncolytic adenoviruses have been used in dozens of cancer clinical trials, but they are usually delivered into the tumor directly.

Shayakhmetov has collaborated for 15 years with structural biologist Phoebe Stewart, professor in the pharmacology department and a member of Cleveland Center for Membrane and Structural Biology at Case Western Reserve University.

“Sometimes even small changes in structural proteins can be catastrophic and prevent assembly of the infectious virus,” Stewart says. “In this case, we modified adenovirus in three places to minimize virus interactions with specific blood factors. We found that the virus still assembles and remains functional for infecting and killing tumor cells.”

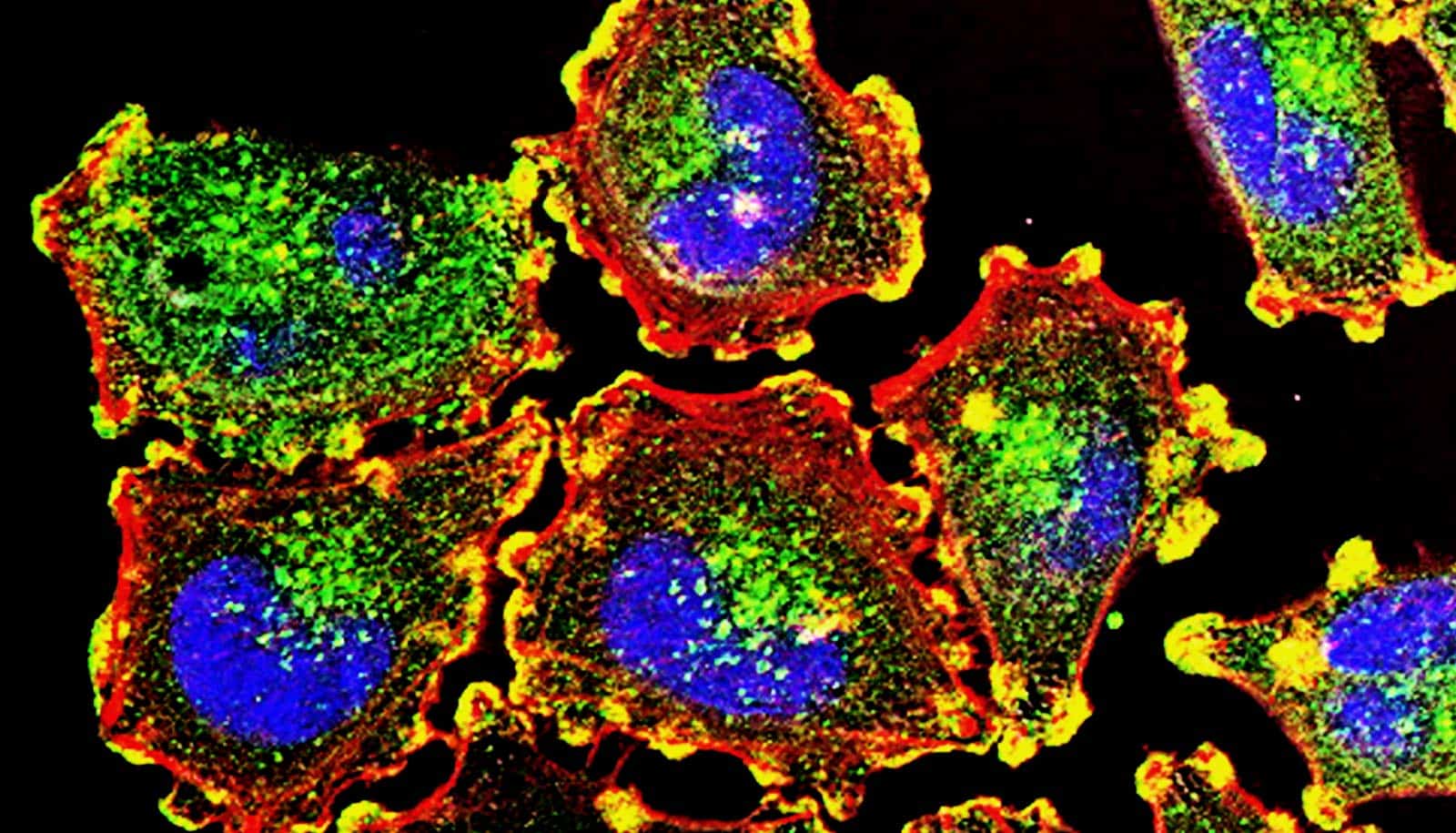

The researchers also replaced part of the adenovirus that interacts with human cellular integrins, substituting a sequence from another human protein, laminin-a1, that targets the virus to tumor cells. Emerson and Stewart obtained a high resolution cryo-electron microscopy structure of the re-engineered virus, demonstrating its structural integrity.

When injected into mice, high doses of standard adenovirus triggered liver damage and death within a few days, but the modified virus did not. The modified virus could eliminate disseminated tumors from some, but not all mice engrafted with human lung cancer cells; a complete response—lack of detectable tumors and prolongation of survival—was observed in about 35% of animals. Tumor sites in the lung were converted into scar tissue, the scientists found. Now, Shayakhmetov’s lab is exploring approaches to further increase the proportion of complete responders.

In the clinic, metastatic lung cancer would be the type of cancer most appropriate to test an oncolytic virus against, Shayakhmetov says. The technology could also be harnessed for gene therapy applications.

Svetlana Atasheva, associate scientist at Emory, and Case Western Reserve graduate student Corey Emerson are the paper’s co-first authors.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the David C. Lowance Endowment Fund, the Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Research Trust, and AdCure Bio funded the work. In addition to using resources at Case Western Reserve, the researchers performed cryo-EM structural and computational at the Electron Imaging Center for NanoMachines at UCLA and the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center.

Source: Emory University