What can those with visibility and influence do—beyond stating support for a particular movement—to combat injustice? Can those with power and privilege advance the interests of others without hijacking or getting in the way of the efforts of the marginalized groups they mean to support?

These are, of course, questions that have dogged activists for generations; there are many wrong answers and few obvious solutions.

For example, when actor and investor Ashton Kutcher announced his intention to co-host a live discussion about gender equality in the workplace on his Facebook page this summer, the social media backlash was swift and fierce.

Many women, including Paradigm CEO Joelle Emerson, pointed out that embedded in the list of potential questions Kutcher proposed for the event—such as “What are the Rules for dating in the work place? Flirting?” and “Should investors invest in ideas that they believe to have less merit so as to create equality across a portfolio?”—were misguided assumptions that actually reinforced the kind of sexism he meant to combat.

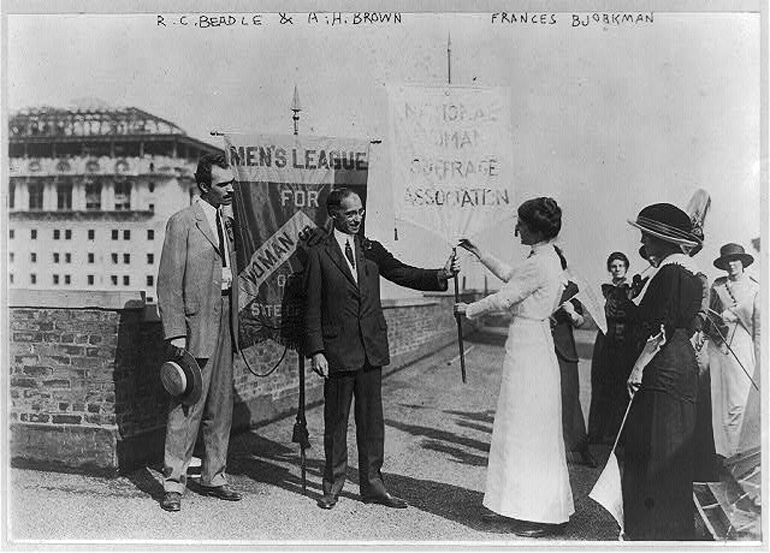

A new book documents how a group of powerful men offered themselves as foot soldiers in the fight for women’s suffrage a century ago. The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote (SUNY Press, 2017) by New York University journalism professor Brooke Kroeger reads almost as a manual for how people might sensitively approach allyship today.

The Men’s League got its unlikely start when the Reverend Doctor Anna Howard Shaw, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, invited Oswald Garrison Villard, publisher of The Nation and The New York Evening Post, to a suffrage convention in Buffalo in October 1908.

Villard insisted that he was too busy to “prepare an elaborate address” for the event but proposed another idea: What if he were to assemble a group of at least one hundred influential men—progressive reformers, public intellectuals, and wealthy industrialists whose names would “impress the public and the legislators”— to lend public support of the cause?

Within a year, Villard had enlisted Greenwich Village writer and John Dewey protégé Max Eastman as the new organization’s secretary, and the hype man’s pro-suffrage speeches and recruitment efforts soon earned headlines like “Male Suffragettes Now in the Field: The Deeper Notes to Join the Soprano Chorus for Women’s Votes.”

By 1911, League membership had grown to 150, with George Foster Peabody, John Dewey, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, and George Creel among the notable men to sign on to the project.

“These were names to knock your socks off,” Kroeger says. “They were big-time financiers, paragons of academia, clergy—leaders in their fields who were running major operations of their own but also took the time to do this.”

Untouchable reputations

In May of that year, 89 Men’s Leaguers, many of them husbands, brothers, or sons of women involved in the movement, joined the second annual Women’s Suffrage Day Parade down 5th Avenue, where they were met with jeers— “hold up your skirts, girls!”—from the crowd of 10,000 spectators.

“It’s hard to imagine a similar issue that everybody could get behind today.”

At a time when public support for a woman’s issue could earn a man ridicule as a “sissy” or worse, having men with untouchable reputations lead the charge was key, as the league’s James Lees Laidlow explained in a 1912 mission statement. “There are many men who inwardly feel the justice of equal suffrage, but who are not ready to acknowledge it publicly, unless backed by numbers. There are other men who are not even ready to give the subject consideration until they see that a large number of men are willing to be counted in favor of it,” he wrote.

The strategy worked, with league chapters soon fanning out from New York across the country. And the growing membership did more than brave hecklers in parades: Taking direction from Shaw, Carrie Chapman Catt, and other NAWSA leaders, men used their connections and political clout to advance the suffragist cause in spheres women couldn’t otherwise have reached.

They argued in favor of women’s suffrage in prestigious publications, sometimes devoting entire issues to the cause; lobbied political operatives to get it into party platforms and served on committees to get suffrage bills before legislatures; pounded the pavement and raised campaign funds in advance of votes on suffrage amendments; and in at least one case even agreed to perform in a suffrage-themed vaudeville routine.

“If you think of who they were and what they were willing to do, it’s sort of remarkable,” Kroeger says—especially considering that in Villard’s original pitch, he’d suggested that league members would have to commit little more than their names to the cause. “It’s also impressive to me that they were Democrats, Republicans, independents, and socialists,” Kroeger adds. “It’s hard to imagine a similar issue that everybody could get behind today.”

Arguments for suffrage

By articulating the case for suffrage in terms that would appeal to their particular audiences, the men helped replace older, sentimental arguments about women’s moral purity with stronger logic about democratic justice.

“Every argument for Negro suffrage is an argument for woman suffrage…”

In one speech, criminal justice reformer Judge William H. Wadhams made reference to the Boston Tea Party, framing the suffrage debate in terms of the right to representation. Women “must obey the law and pay the penalties of the law,” he reasoned, adding, “those who have the penalties imposed should have the privileges of citizenship.”

The black civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois repeatedly turned the pages of his magazine Crisis over to the cause, at one point urging black voters to temporarily forgive the “reactionary attitude of most of white women to our problems,” and take a longer view. “Every argument for Negro suffrage is an argument for woman suffrage; every argument for women suffrage is an argument for Negro suffrage,” he wrote. “Both are great movements in democracy.”

Woodrow Wilson’s change of heart

The league members’ efforts were deliberately designed to serve NAWSA’s two-pronged strategy—to campaign for women’s suffrage in individual states while also advocating for an amendment to the national Constitution. Kroeger offers a detailed account of the men’s involvement in the years of legislative maneuvering it took to get the little word “male” removed from the section of the New York State constitution that spelled out who was allowed to vote. (An amendment made it to the ballot but failed to garner enough votes in 1915, so it took a subsequent vote in November 1917 to finally pass it.)

“When else, before or since, have men ever behaved that way over a women’s issue?”

But she also suggests that members of the Men’s League, which included close friends, confidants, and supporters of Woodrow Wilson, may also have also played a pivotal role in shaping the president’s thinking on the issue at the federal level in the tense run-up to the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

For years, Wilson “hemmed and hawed and dodged” when asked about his personal views on women’s suffrage, Kroeger says, demurring with lines about states’ rights and the moral complexity of the question that will sound familiar to those who tracked public figures’ ever-evolving stances on more recently polarizing issues such as marriage equality.

It’s impossible to know what finally pushed Wilson to endorse the idea in a 1918 speech to Congress—it could have been women’s contributions to World War I, or the militant suffragists picketing on his lawn—but Kroeger suggests that the Men’s Leaguers in his inner circle must have made an impression.

George Creel, for example, became Wilson’s head of the US Committee on Public Information in 1917. And that same year, another Wilson appointee, Dudley Field Malone, resigned from his post in frustration over the administration’s stalling on the suffrage question. “I think it is high time that men in this generation, at some cost to themselves, stood up to battle for the national enfranchisement of women,” he wrote.

‘The women did it’

Curiously, Kroeger found, the suffrage movement receives little or no mention in the official biographies and memoirs of many of these notable men, even though Men’s League participation in NAWSA activism was widely—even obsessively—covered by the press at the time. This could be simply because they were famous for plenty of other things (Villard was a founder of the NAACP, for example), and helping get women the vote didn’t necessarily top their personal lists of achievements.

But Kroeger also uncovered evidence to suggest that the men may have written themselves out of this history more or less deliberately—in acknowledgement that they’d only come in for the final push for suffrage, after decades of tireless organizing by generations of women going back to the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848.

Laidlaw once said as much, in a speech after the passage of the New York State amendment in 1917: “The women did it. But not by any heroic action, but by hard, steady grinding and good organization.” He added: “We men too have learned something, we who were auxiliaries to the great women’s suffrage party. We have learned to be auxiliaries.”

“I got chills when I read that line,” Kroeger reflects. “When else, before or since, have men ever behaved that way over a women’s issue?”

Source: New York University