The Lindbergh baby kidnapping case is the “perfect story,” says Tom Doherty.

“I’m a media person, and like most of America in the age of Netflix, I have an obsession with true crime,” says Doherty, professor of American studies at Brandeis University. “The Lindbergh kidnapping case is right at the intersection—it’s a crime story and a media story.”

There’s a lot of writing about the kidnapping and murder of Charles Lindbergh, Jr., the subsequent investigation, and the trial and conviction of Bruno Richard Hauptmann, but in a new book, Little Lindy Is Kidnapped: How the Media Covered the Crime of the Century (Columbia University Press, 2020), Doherty takes on a new angle.

“I found most of the books about the case are sort of true crime accounts about what happened during the kidnapping, the trial, whether Hauptmann was guilty or not guilty, those kinds of questions,” Doherty says. “Nobody had done a book exclusively on the media revolution.”

Here, Doherty talks about the case and why it was so important:

What makes this such an important story with respect to modern media?

It’s really the first time we see the three pillars of the modern media—print journalism, radio, and newsreels, which later become television and digital media—all coming together.

Radio has reached a level of penetration, where most Americans have one in their home, and that means they have access to real-time news broadcasting. That’s what they have ever after. Whether it’s broadcasting or digital, it is instantaneous information coming into your home.

Film newsreels, meanwhile, are still emerging as a media. They have become quite prevalent at this point, but they haven’t been established to have First Amendment rights, and they hadn’t really covered an event like this before.

The Lindbergh family’s footage of the Lindbergh baby was the first time that home movie footage was ever incorporated into newsreels.

Newspapers are massive at this time. There were 12 daily newspapers in New York in 1932, and they all sent out squadrons of reporters to cover this story, which people are obsessively interested in.

At this time, Lindbergh is the most admired man in America. It’s the kind of sensational story that outrages all of America. It really is the crime of the century.

What makes it the ‘crime of the century?’ What separates it from other fame or celebrity-driven type crime stories?

What distinguishes it from cases like O.J. Simpson or the Manson murders, or some of the other notorious crimes is that our relationship to someone like O.J. is almost totally vicarious. He’s a celebrity who we kind of knew, but we’re not emotionally engaged with him.

Everybody knew who Charles Lindbergh was and loved him. His flight from New York to Paris was an extraordinary feat of personal courage. He had earned his fame, and he had not yet ruined his reputation with his anti-Semitism and isolationism that became apparent in the 1940s.

People knew his wife, they knew the baby, and there was a deeper emotional connection to him on the part of virtually every American.

And the story slowly, dramatically unfolds. The baby is kidnapped in March 1932. A ransom payment is made in April. The body is found in May. It isn’t until September of 1934 that Bruno Richard Hauptmann is arrested.

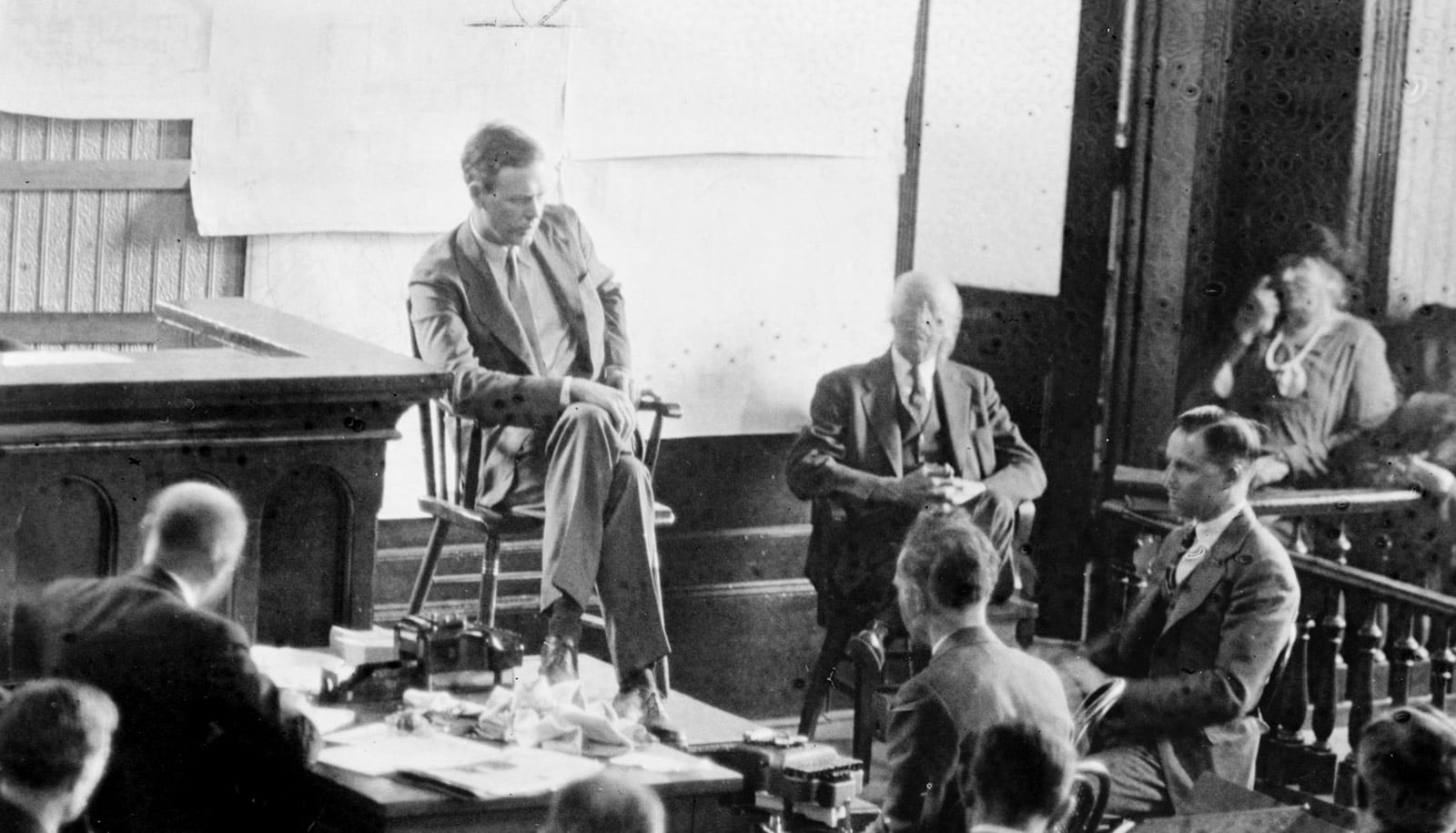

His murder trial begins in January 1935 and runs for over a month, and every journalist, every novelist, anybody with any sort of journalistic ambition or back story is in Flemington, New Jersey to cover this case because everybody knows this is the trial of the century. So, you’ve got the best journalistic talent ever assembled covering it. The crime of the century gives way to the trial of the century.

How does this convergence of fame, crime, and media play out in the trial?

One of the things that happens at the trial, which is sort of true forever on, is the forensic evidence becomes fascinating to people. You don’t have shootouts or dramatic confrontations. There are no fingerprints, there’s no gun. Nobody can really place Hauptmann at the crime scene.

So, you’ve got to follow the forensic trail. And what you have is this sort of relentless accumulation of forensic detail, which together leads unmistakably to Bruno Richard Hauptmann. Things like ransom money bank records, handwriting analysis, analysis of the wood grain of a ladder. People are obsessed with these details. They are reading three thousand words a day in The New York Times on the case.

This is something you see in the true crime genre today with these 15-part series that lead you through every little nook and cranny of the investigation. Some of that starts with the Lindbergh case.

The other big piece of the trial from a media perspective is the newsreels. Newsreels were allowed into the courtroom, but the judge did not allow them to record during witness testimony. But when Hauptmann takes the stand, it is too irresistible and they surreptitiously record it and release the footage. This is an important moment in giving motion picture journalism some of the prerogatives of the First Amendment.

At the same time, the newsreel coverage of the case is viewed as so sensational, so outrageous, that it led the American Bar Association to adopt the canon in their code of ethics that says cameras should not be allowed in the courtroom. Decades later, state courts began to allow cameras, but they are banned in federal court to this day.

What is the lasting legacy of the Lindbergh kidnapping case?

There are many legacies, but as I see it, there are three significant ones.

First, there’s the cultural and literary legacy. This case has haunted literary artists and other artists since it happened.

Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America, for example. Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. The little boy in the white suit, that’s the Lindbergh baby. As a young boy growing up Sendak was terrified that something could happen to him because if Charles Lindbergh’s son can be kidnapped and even a little boy in Brooklyn like him could be kidnapped.

Then there is legacy of the FBI. From here on, any time there is a need for a level of forensic expertise, we go to Washington.

This is in part because the New Jersey State Police so badly bungled evidence and handled the case with extraordinary incompetence. The Bureau of Investigation, led by a young J. Edgar Hoover, came in and not only handled the case with far greater competency, they make sure their competency is highlighted in the press. It’s the beginning of a new standard.

Finally, Congress passes a law that summer making kidnapping a federal crime and later a capital offense. If you kidnap a child for ransom in America, you face the death penalty.

Source: Brandeis University