Astronomers have developed a new, more accurate method for measuring the masses of solitary stars.

Getting accurate measurements of how much stars weigh not only plays a crucial role in understanding how stars are born, evolve, and die, but it is also essential in assessing the true nature of the thousands of exoplanets now known to orbit most other stars.

The method is tailor-made for the European Space Agency’s Gaia Mission, which is in the process of mapping the Milky Way galaxy in three dimensions, and NASA’s upcoming Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which is scheduled for launch next year and will survey the 200,000 brightest stars in the firmament looking for alien earths.

One at a time

“We have developed a novel method for ‘weighing’ solitary stars,” says Keivan Stassun, a professor of physics and astronomy at Vanderbilt University who directed the development. “First, we use the total light from the star and its parallax to infer its diameter. Next, we analyze the way in which the light from the star flickers, which provides us with a measure of its surface gravity. Then we combine the two to get the star’s total mass.”

Stassun and his colleagues—Enrico Corsaro from INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Catania in Italy, Joshua Pepper from Leigh University, and Scott Gaudi from Ohio State University—describe the method and demonstrate its accuracy using 675 stars of known mass in an article in the Astronomical Journal.

Traditionally, the most accurate method for determining the mass of distant stars is to measure the orbits of double star systems, called binaries.

Newton’s laws of motion allow astronomers to calculate the masses of both stars by measuring their orbits with considerable accuracy. Fewer than half of the star systems in the galaxy are binaries, however, and binaries make up only about one-fifth of red dwarf stars that have become prized hunting grounds for exoplanets, so astronomers have come up with a variety of other methods for estimating the masses of solitary stars.

The photometric method that classifies stars by color and brightness is the most general, but it isn’t very accurate. Asteroseismology, which measures light fluctuations caused by sound pulses that travel through a star’s interior, is highly accurate but only works on several thousand of the closest, brightest stars.

“Our method can measure the mass of a large number of stars with an accuracy of 10 to 25 percent. In most cases, this is far more accurate than is possible with other available methods, and importantly it can be applied to solitary stars so we aren’t limited to binaries,” Stassun says.

Subtle flickers

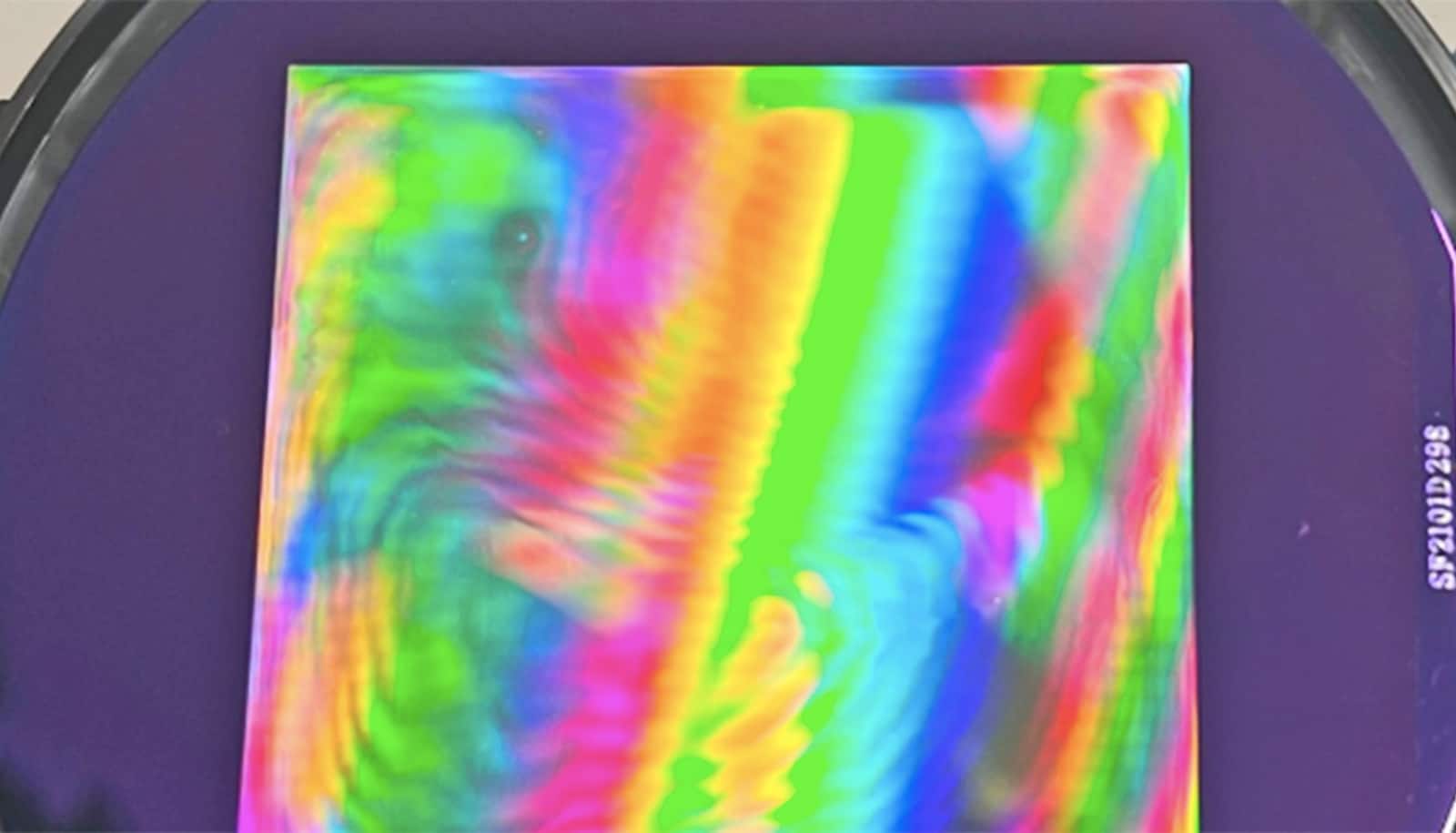

The technique is an extension of an approach that Stassun developed four years ago with graduate student Fabienne Bastien, who is now an assistant professor at Penn State. Using special data visualization software developed by a neuro-diverse team of Vanderbilt astronomers, Bastein discovered a subtle flicker pattern in starlight that contains valuable information about a star’s surface gravity.

Extreme galaxy merger makes stars in a ‘frenzy’

Last year, Stassun and his collaborators developed an empirical method for determining the diameter of stars using published star catalog data. It involves combining information on a star’s luminosity and temperature with Gaia Mission parallax data. (The parallax effect is the apparent displacement of an object caused by a change in the observer’s point of view.)

“By putting together these two techniques, we have shown that we can estimate the mass of stars catalogued by NASA’s Kepler mission with an accuracy of about 25 percent and we estimate that it will provide an accuracy of about 10 percent for the types of stars that the TESS mission will be targeting,” says Stassun.

Establishing the mass of a star that possesses a planetary system is a critical factor in determining the mass and size of the planets circling it.

An error of 100 percent in the estimate of the mass of a star, which is typical using the photometric method, can result in an error of as much as 67 percent in calculating the mass of its planets. This is roughly equivalent to the difference between a Mercury and an Earth. So, it is extremely important in properly assessing the nature of all the alien worlds that astronomers have begun detecting in recent years.

Massive primordial galaxy will soon get even bigger

The National Science Foundation PAARE grant and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program funded the research.

Source: Vanderbilt University