Proteins central to cell division may also play a key role in keeping stem cells in their immature, undifferentiated state and allowing cancer’s spread.

The study illuminates the basic biology of stem cells, and suggests a new molecular handle for controlling them. Stem cells have regenerative properties with the potential to revolutionize medicine, but that potential is still far from being realized because too little is known about how these cells work.

The study also points to a better understanding of how cancer cells manage to sustain rapid cell division without triggering cell death.

“Studies like this help explain the underlying biology of rapidly dividing cells and may inform the development of future therapies, for example stem cell therapies or cancer treatments,” says study senior author Jean Cook, a professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the University of North Carolina, member of the university’s Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, and the associate dean for graduate education at the UNC School of Medicine

MCM loading & cell division

The study focused on a cluster of proteins called the minichromosome maintenance (MCM) complex, known to be a crucial factor in cell division. A cell prepares for the division process in part by loading MCM complexes onto its chromosomes. These complexes are needed to properly unwind chromosomal DNA during cell division so that two new sets of chromosomes—one for each daughter cell—can be formed from the original set.

“If MCM loading isn’t completed successfully prior to cell division, there will be a risk of major DNA mutations and death for the resulting daughter cells,” says study first author Jacob Matson, a PhD candidate in the Cook laboratory who performed most of the experiments over the course of three years.

Despite the importance of MCM loading, cell types vary greatly in the time they have to prepare for cell division. Stem cells, for example, go through this preparatory phase—known as the G1 phase of the cell cycle—in a small fraction of the time spent by more mature, “differentiated” cells, such as skin cells or heart muscle cells.

Can stem cells restore hearing without causing cancer?

How stem cells manage to quickly transition through the G1 phase without risking incomplete MCM loading and resultant DNA damage has been a mystery.

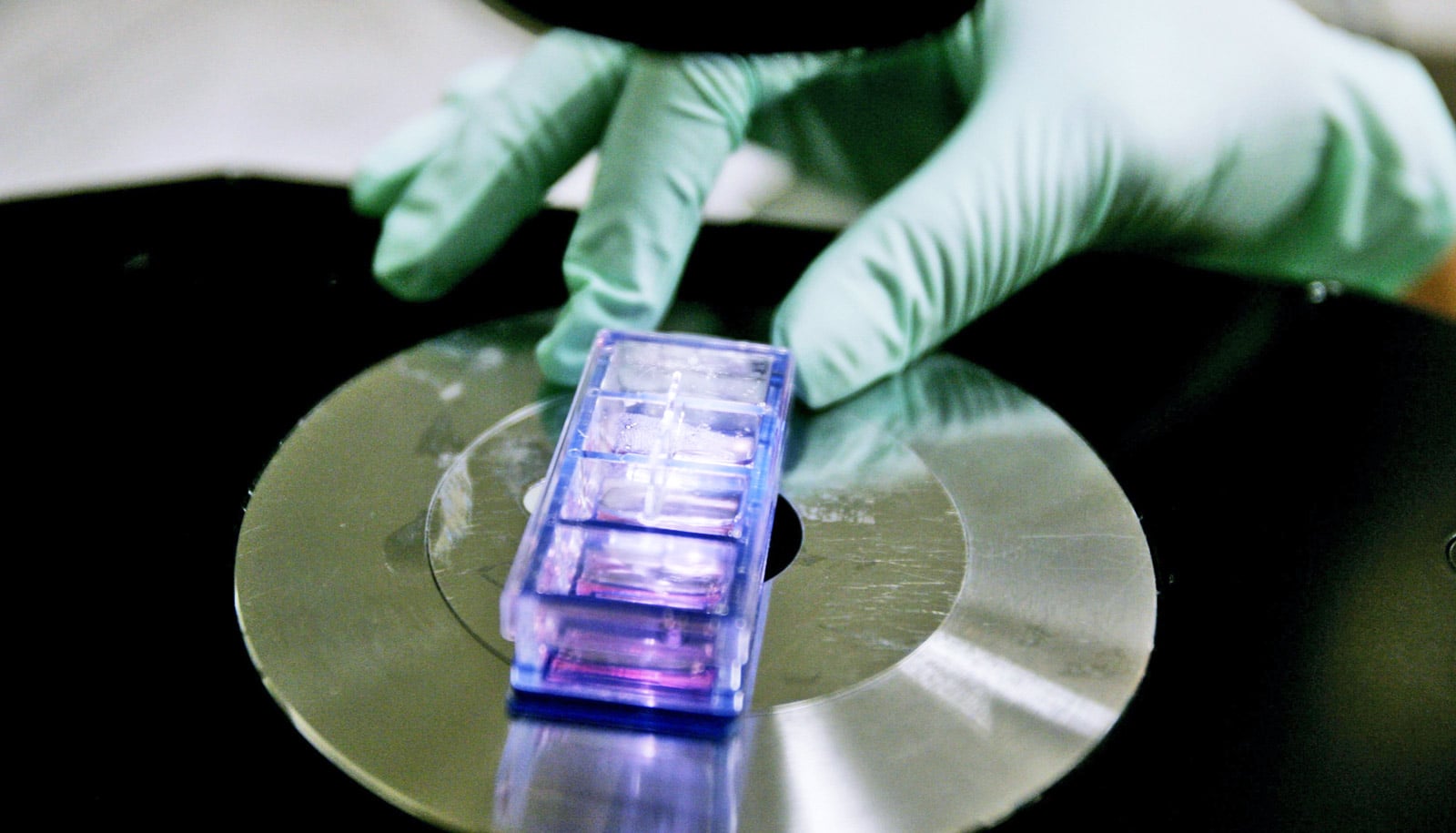

One possibility is that stem cells somehow maintain higher MCM loading rates, so that they can accomplish the necessary loading within their shorter G1 windows. To investigate, the researchers used a sensitive assay they developed to measure the speed of MCM loading.

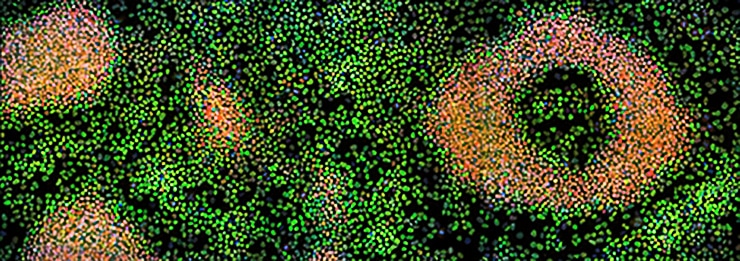

They found that stem cells do indeed load MCM complexes much more quickly than mature, differentiated cells. In fact, chemically forcing these stem cells to differentiate into more mature cells markedly slowed the maturing cells’ MCM loading rates.

A way to create stem cells?

The coupling of MCM loading and cell differentiation worked in the other direction too.

“Inducing slower MCM loading in stem cells caused them to differentiate more quickly,” Matson says.

The results suggest that MCM loading rate is an important factor in cell development, and that speedy MCM loading in particular is something that stem cells do to maintain themselves in the immature, stem cell state.

Water volume steers stem cells to become bone or fat

The findings also hint that inducing rapid MCM loading in more mature cells may help turn them back into stem cells. The “reprogramming” of ordinary cells into stem cells—known as induced pluripotent stem cells—is now done routinely in laboratories around the world and is seen as a potential future source of stem cells for therapies. But the standard methods used for this reprogramming are not as efficient as researchers would like.

“Conceivably, artificially speeding up MCM loading would make this reprogramming process more efficient,” Cook says.

She and her colleagues now are trying to understand better the biological mechanisms by which cells move their MCM loading rates up or down.

Cancer’s spread

The researchers also are now studying the role of MCM loading rates in cancers. For example, some cancer cells are highly prone to DNA errors when dividing. Cook and colleagues suspect that in some cases this “genomic instability” arises from the cells’ failure to boost their MCM loading rates as their cell division speeds up.

Other cancer cells, particularly those with stem-like properties, may succeed in boosting their MCM loading rates to keep themselves viable. If so, drugs that reduce the MCM loading rate could force such cancers into a slower-growing, less malignant state, or even kill them by making them vulnerable to excess DNA damage during cell division.

“We suspect that rapid MCM loading is an important aspect of how cancer cells manage to grow fast without excessively damaging their DNA. It’s a target worth pursuing,” Cook adds.

The researchers report their findings in the journal eLife.

Additional researchers who collaborated for the study are from UNC and the University of Minnesota.

The National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the W.M. Keck foundation provided funding for the research.

Source: UNC-Chapel Hill