The long-lost capital of the ancient Maya kingdom Sak Tz’i’ has turned up in the backyard of a Mexican cattle rancher.

Charles Golden, associate professor of anthropology at Brandeis University, in collaboration with Brown University bioarchaeologist Andrew Scherer, and a team of researchers from Mexico, Canada, and the United States, began excavating the site in June 2018.

Among their findings is a trove of Maya monuments, one of which has an important inscription describing rituals, battles, a mythical water serpent, and the dance of a rain god. They’ve also found remnants of pyramids, a royal palace, and ball court.

Cows grazed while the scientists worked. Ensuring the animals didn’t trample the excavation, fall into deep pits, or soil the working area with dung proved a daily challenge.

Golden and his fellow researchers believe the archaeological site, named Lacanja Tzeltal for the nearby modern community, was the capital of the Sak Tz’i’ kingdom, located in what is today the state of Chiapas in southeastern Mexico. It was likely first settled by 750 BCE and then occupied for over 1,000 years.

Researchers have been looking for evidence of Sak Tz’i’ since 1994 when they identified references to it in inscriptions found at other Maya excavation sites. Sculptures in museums around the world also mention the realm.

Sak Tz’i’ was by no means the most powerful of the Maya kingdoms, and its remnants are modest compared to the more well-known sites of Chichen Itza and nearby Palenque.

But Golden says finding Sak Tz’i’ is still a major advance in our understanding of ancient Maya politics and culture. He likens it to trying to put together a map of medieval Europe from historical documents and reading about someplace called France without knowing where it was located. “It’s that big a piece of the puzzle,” Golden says.

Golden and his collaborators report their findings in the Journal of Field Archaeology.

Clues to the Maya kingdom

In June 2014, in search of a dissertation topic, University of Pennsylvania student Whittaker Schroder, who worked on Golden’s project, drove around Chiapas looking at archaeological digs. Toward the end of his stay, a man selling carnitas on the side of the highway started waving at him as he rode by.

Schroder thought he wanted him to buy his food. A vegetarian, he kept going.

Finally, a day before his departure, Schroder decided he had nothing to lose and pulled over.

The man wasn’t interested in selling Schroder carnitas after all. He told Schroder his friend had discovered an ancient stone tablet. He knew Schroder, who’d been doing research in the area for several years, was interested in the Maya. Would the graduate student like to see it?

The next day Schroder and another grad student, Jeffrey Dobereiner of Harvard, met with the vendor’s friend, a cattle rancher, convenience store owner, and carpenter, and confirmed the tablet’s authenticity. He then passed on word to Golden and Scherer.

It took another five years to negotiate permission to excavate on the property. In Mexico, cultural patrimony like ancient Maya sites are considered the property of the state, so the rancher worried that the government might confiscate his land. Golden and Scherer worked with him and government officials to make sure that this wouldn’t happen.

Daily life in Sak Tz’i’

The Sak Tz’i’ kingdom was relatively small, straddling what is today the Mexican-Guatemala border. Why it was called Sak Tz’i’, which means white dog, is unknown.

The Maya believed royalty could become one with or even transform into a god.

Commoners lived in the countryside harvesting a wide variety of crops and making pottery and stone tools. Golden and his colleagues found the remnants of what was likely the city’s marketplace where people brought these goods to sell them.

The kingdom’s residents also came to the city to attend ceremonial ball games in which players kept a solid rubber ball, sometimes as heavy as twenty pounds, bouncing back and forth across a narrow playing field using their hips and shoulders.

On the northeastern end of the city are the ruins of a 45-foot high pyramid and several surrounding structures that served as elite residences and sites for religious rituals.

The center of religious and political activity was the “Plaza Muk’ul Ton,” or Monuments Plaza, a 1.5-acre courtyard where the people gathered for ceremonies. A staircase leads from the plaza to a towering platform, where temples and reception halls were arrayed and members of the royal family once held court and might have been buried.

Neighbors and enemies

Sak Tz’i’ had the misfortune of being surrounded on all sides by more powerful states. For the inhabitants of the capital and countryside, this meant the perpetual threat of warfare and violent interruptions of daily life.

Golden and his collaborators have found evidence that the capital was surrounded on one side by steep-walled streams. On the other side, masonry walls aimed to keep out invaders.

These fortifications weren’t always effective. Inscriptions on one monument tell of a time when at least a portion of the city was set ablaze during a conflict with neighboring kingdoms.

Ultimately, the survival of Sak Tz’i may have depended as much on its ability to make peace with its neighbors—and even play them off of each other—as its military strength.

Golden says this is one of the reasons Sak Tz’i holds so much interest for researchers. There’s little information about how mid-size Maya realms maneuvered and managed to persist in the face of constant hostilities from more powerful kingdoms.

Water serpent on a tablet

So far, researchers have found dozens of sculptures among the ruins at the Sak Tz’i site, though looters and millennia of rain, forest fires, and lush tropical vegetation have damaged or degraded many.

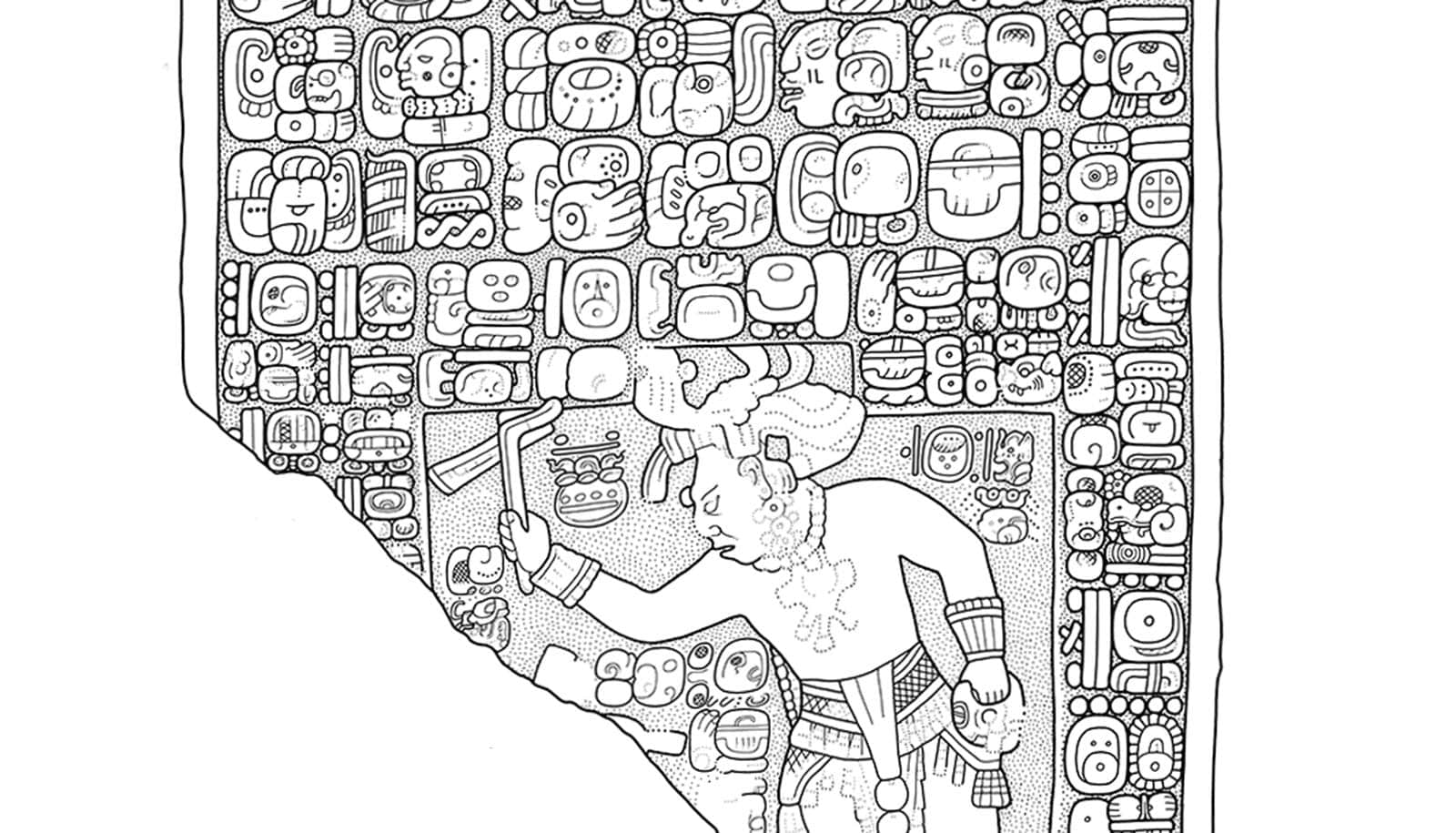

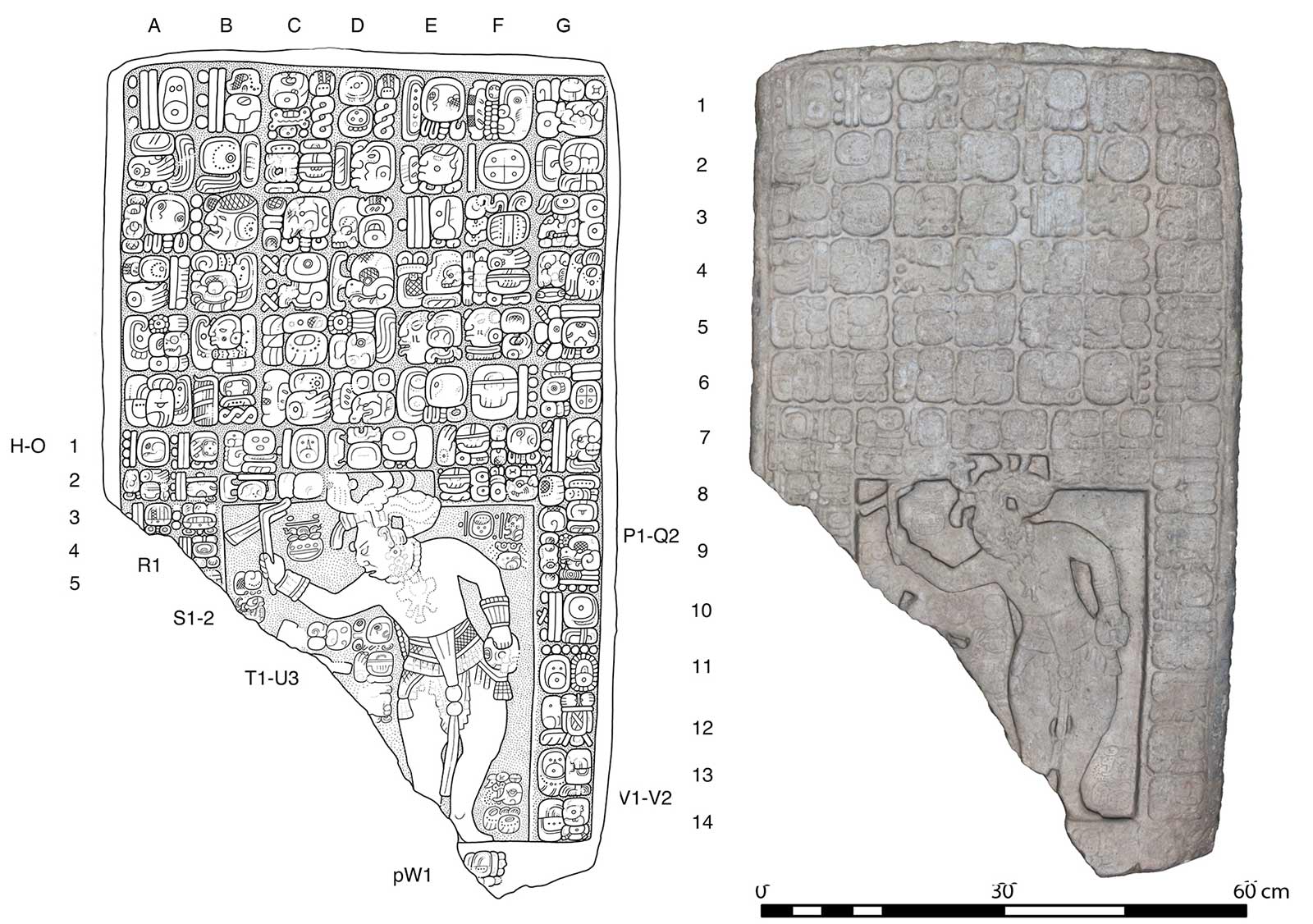

But the best-preserved sculpture is the one that the carnitas vendor originally showed to Schroder. A two- by four-foot tablet, its inscriptions tell stories about a mythical water serpent—which poetic couplets describe as “shiny sky, shiny earth”—and several elderly, stony gods whose names aren’t given. There are also accounts of the lives of dynastic rulers.

Another inscription tells of a mythic flood, while others list what are probably historic dates for the births and battles of various rulers, including a king named K’ab Kante’.

This intertwining of myth and reality is typical of Maya inscriptions and had special meaning for ancient scribes and readers.

At the bottom of the tablet is a dancing royal figure. The Maya believed royalty could become one with or even transform into a god. In this case, the ruler is dressed as the rain god connected to violent tropical storms, Yopaat.

In his right hand, he carries an axe that is the lightning bolt of the storm, which has a deified aspect named K’awiil. In his left hand, the figure carries a “manopla,” a stone gauntlet or bludgeon used in ritual combat.

What will they find next?

With the permission of the Mexican government and the local community, Golden, Scherer, and the rest of their team plan to return to Sak Tz’i’ in June.

They will continue mapping the ancient city using, among other tools, a technique called LIDAR (light detection and ranging) in which a laser finder is mounted on an airplane or drone to reveal architecture and topography even beneath dense jungle canopy.

Team members will stabilize ancient buildings in danger of collapse, and further document those sculptures still among the ruins. They will also further explore the area that they believe is a marketplace, hoping to find more evidence of the goods once for sale there and workshops that produced stone tools and other products.

Golden says the scientists are paying particular attention to working closely with the local community. “To be truly successful,” he says, “the research will need to reveal new understandings of the ancient Maya and represent a locally meaningful collaboration with their modern descendants.”

Source: Brandeis University