Interviews with unhoused people who have recently experienced opioid overdose indicate more effective ways to deal with places like the “Mass and Cass” intersection in Boston, say researchers.

Massachusetts Avenue at Melnea Cass Boulevard in Boston is a noisy stretch of urban concrete—wide, traffic-clogged roads competing for space with businesses, parking lots, emergency shelters, health clinics, and a smattering of trees—that’s become a magnet for people who are unhoused and grappling with an opioid addiction.

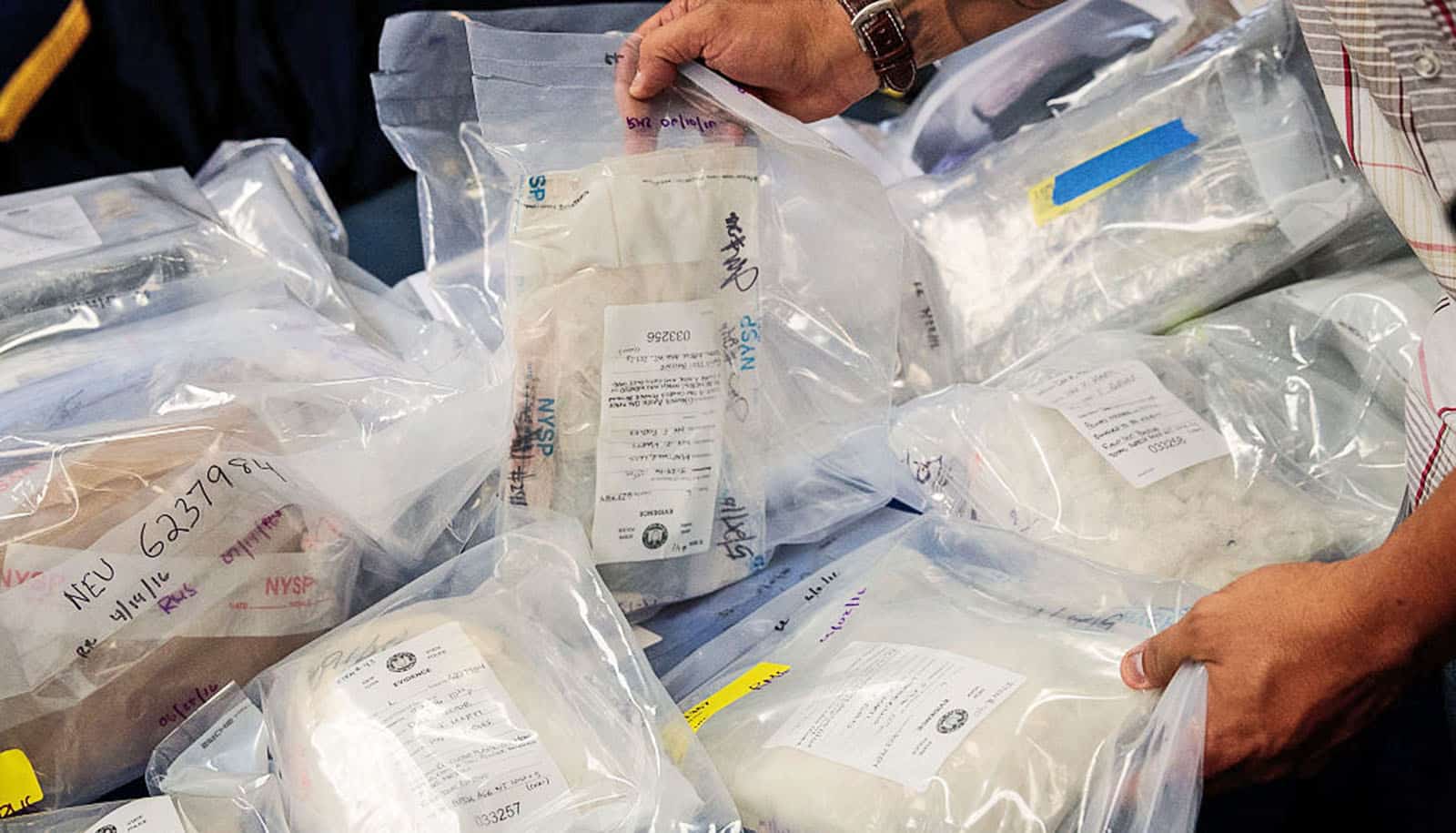

Until the city moves them along, many of the hundreds of people who are drawn to the area sleep in tents and ramshackle shelters. In a recent story, the Boston Globe called the intersection a “notorious open-air illicit drug market.”

Boston has made multiple efforts over the years to address the complex problems that have gripped Mass and Cass. It’s started helplines to report discarded needles, removed tents, arrested people on the streets, diverted folks to shelter and treatment facilities, built a day center, and boosted investment in affordable housing. But the people and tents always seem to return.

It’s a familiar story across the country. Los Angeles, New York, and Philadelphia have all seen opioid overdose deaths rise in recent years, particularly among people experiencing homelessness. In Massachusetts, the crisis has taken a grim toll. There were more than 2,300 opioid overdose deaths in the state in 2022 and 500 between January and March of this year alone, according to the state’s Department of Public Health.

In an effort to find new ways of reducing the number of deaths, Boston University researchers spoke with opioid overdose survivors experiencing unsheltered homelessness in the streets around Mass and Cass. Those they interviewed talked about a series of common issues, including inadequate housing and shelter options and a chaotic and dangerous environment that stymied their recovery goals. The 29 interviewees—who had all overdosed within the past three months—also had ideas for improving available services.

The researchers conclude that Boston should consider “additional low-barrier housing services (i.e., including harm reduction resources and without ‘sobriety’ requirements)” to help tackle addiction and homelessness. The results appear in the International Journal of Drug Policy.

“This study was an opportunity to hear directly from people about their experiences,” says Simeon Kimmel, an assistant professor of medicine at Boston University’s Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine and an infectious diseases and addiction medicine physician at Boston Medical Center. “It has been really meaningful to take a more systematic approach to understanding the patients that I care for, what their lives are like, and what they’re looking for.” Kimmel is also medical director at BMC’s Project TRUST, a harm-reduction-focused drop-in center that offers medical resources, education programs, and connections to broader health care services.

The latest paper is part of a larger project, the Boston Overdose Linkage to Treatment Study, examining inequities in access to treatment after an opioid overdose. The study is a collaboration among the university, the Boston Public Health Commission, and the Institute for Community Health (ICH). Funding for the work came from RIZE Massachusetts Foundation, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the university’s Department of Medicine Career Investment Award.

Here, Kimmel and his fellow researcher Ranjani Paradise, ICH’s director of evaluation, talk about their research—and what they heard from the people who call Mass and Cass home:

What were the main stories that emerged from your conversations with people on the streets near Mass and Cass?

Paradise: People talked about their experience with housing in Boston, their struggles around the capacity of the housing system and shortages of housing, and their dissatisfaction with the shelter services. Many of the people were choosing to live on the street over accessing shelters. And just, I think, commenting more broadly on an environment without stability and safety—not having that foundation they could rely on when they were thinking about bigger goals around their treatment and recovery.

We also heard a lot about participants’ experiences of being in the Mass and Cass area, about what it’s like to be in an area with a lot of public drug use. Some people talked about feeling a sense of safety there, because there are a lot of people around who can reverse an overdose; other people had more negative perspectives of unsafe behaviors being overlooked.

Kimmel: People seemed not to feel welcome in certain kinds of services, even services that might be designed for people experiencing homelessness, like the shelters. But they did feel welcome in some of the more low-barrier harm-reduction–focused programs—like the Engagement Center and Project TRUST—which are more focused specifically on the needs of people who use drugs and don’t require abstinence to engage in them. One of the messages that came out of these interviews was the need for more of those kinds of programs where people feel welcome, where they feel like they can access resources that they need, and a sense that those programs shouldn’t all be in one location. People felt like living in that area was quite chaotic: not knowing where they’re going to sleep, not being able to have security around their belongings and medications, being exposed to violence. All of that was quite destabilizing, even if they were motivated to decrease or stop their substance use.

The other key point that came out was that people really wanted their experiences, their voices, to be included in the decisions, programs, and policies that impact their lives. They felt too often their voices and their experiences were being marginalized or were not being centered in the development of programs.

Did anything come out of your conversations that might surprise people?

Paradise: Almost every single person had done treatment programs. Some people had done multiple programs. I think sometimes there’s a public perception that there isn’t a motivation or desire to engage in treatment or to move toward recovery. That really was not the story that people were telling us. It was much more about how hard it is without having a basic foundation of stability. Sometimes, people would go to treatment, but without a place to live when they’re done, they end up right back where they started. The situation is a lot more complex and nuanced than maybe people realize. Substance use is a piece of someone’s overall life—it’s not something you can treat or try and address in isolation from broader circumstances.

What’s happening at Mass and Cass can seem like a very Boston-specific problem, but how true is that?

Kimmel: There are neighborhoods where there are public drug scenes, communities of people who are really struggling with substance use. And you see the overlap of substance use and homelessness in a lot of cities. And one way that cities have responded is to kind of push those people to one neighborhood. It’s not a problem that’s unique to Boston for sure.

What message would you have for any Boston-area politicians and policymakers reading this? What would you like them to do differently?

Kimmel: The substance-use treatment system is structured to be very linear. People access it through detox programs; they spend a certain amount of time in detox programs, and then they go to residential treatment programs. And then they go from there to a halfway house or a sober living environment. And in each step, there’s a very large drop-off in people who aren’t able to access the next step. Anytime anybody experiences a brief period of substance use, they get routed back to the beginning. There are other substance-use treatment systems that are outpatient-based that don’t require people to exclusively be abstinent in order to engage. But the treatment systems that include a place to stay require abstinence. And so people who are either ambivalent or unable to maintain abstinence for an extremely long period of time struggle.

The movement toward offering low-barrier housing options with embedded harm-reduction services is an important innovation. It offers people a place to be safer while they’re in a period where they’re using, and [allows them to] access other resources—you can deliver clinical services to people, engage with people in a much more meaningful way than you can when people are on the street.

This is all happening on BMC’s doorstep. What is the hospital doing to help?

Kimmel: BMC offers a wide range of substance-use treatment programs, many of them outpatient. And actually, over the last year, we ran one of the harm-reduction housing programs at the [former] Roundhouse [hotel], which is a model that is in some ways what the people that we interviewed were really calling for—more opportunities to be housed and to be treated with dignity and respect, even if they are using substances. BMC has made a real commitment to trying to address a lot of these challenges.

What’s the final thing you’d like people to take away from your study or about the people living around Mass and Cass?

Kimmel: People told us—and this matches my clinical experience—that the services that are designed for people experiencing homelessness don’t always feel welcoming and acceptable to them. And they’re voting with their feet, right? Sleeping on the street or bouncing around and not engaging in the shelter system. And so there needs to be changes to make that are more acceptable to people.

Maybe this is the elephant in the room, but currently, there’s no supervised injection facilities or overdose prevention sites in Boston or in Massachusetts, or at least no sanctioned ones. And as a result, this area [Mass and Cass] becomes a de facto overdose prevention site, where people are using in a group, where there’s some monitoring, but using in a much less safe way than they could if there were real services that were designed to deliver that kind of programming.

Source: Boston University