The Mars rover Opportunity finally ended its mission on February 13—three weeks after its 15th anniversary and long past its 90-day warranty.

Over the course of its scientific mission, Opportunity returned hundreds of thousands of images and reshaped our understanding of Mars’ surface for nearly 14 and a half years. Opportunity’s twin, Spirit, challenged by a rocky and rough terrain, officially ended its mission in 2011.

“It’s hard to put the scientific payoff yet into context, since the mission has just come to a close,” says Steve Squyres, professor of physical sciences at Cornell University and the principal scientific investigator for the Mars Exploration Rovers mission. “Both rovers together revealed that ancient Mars was a very, very different place from modern-day Mars; it was more habitable, more Earthlike than Mars is today.”

Opportunity launched just before midnight July 7, 2003, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Base, Florida. It flew 283 million miles to Mars over six months and 19 days. As the craft landed January 25, 2004, cradled in its cocoon of air bags, it bounced 26 times, traveling 220 yards on the surface, before settling in Eagle Crater on Meridiani Planum—a plains area on the red planet.

Squyres called the landing a “hole in one.”

Hints of water

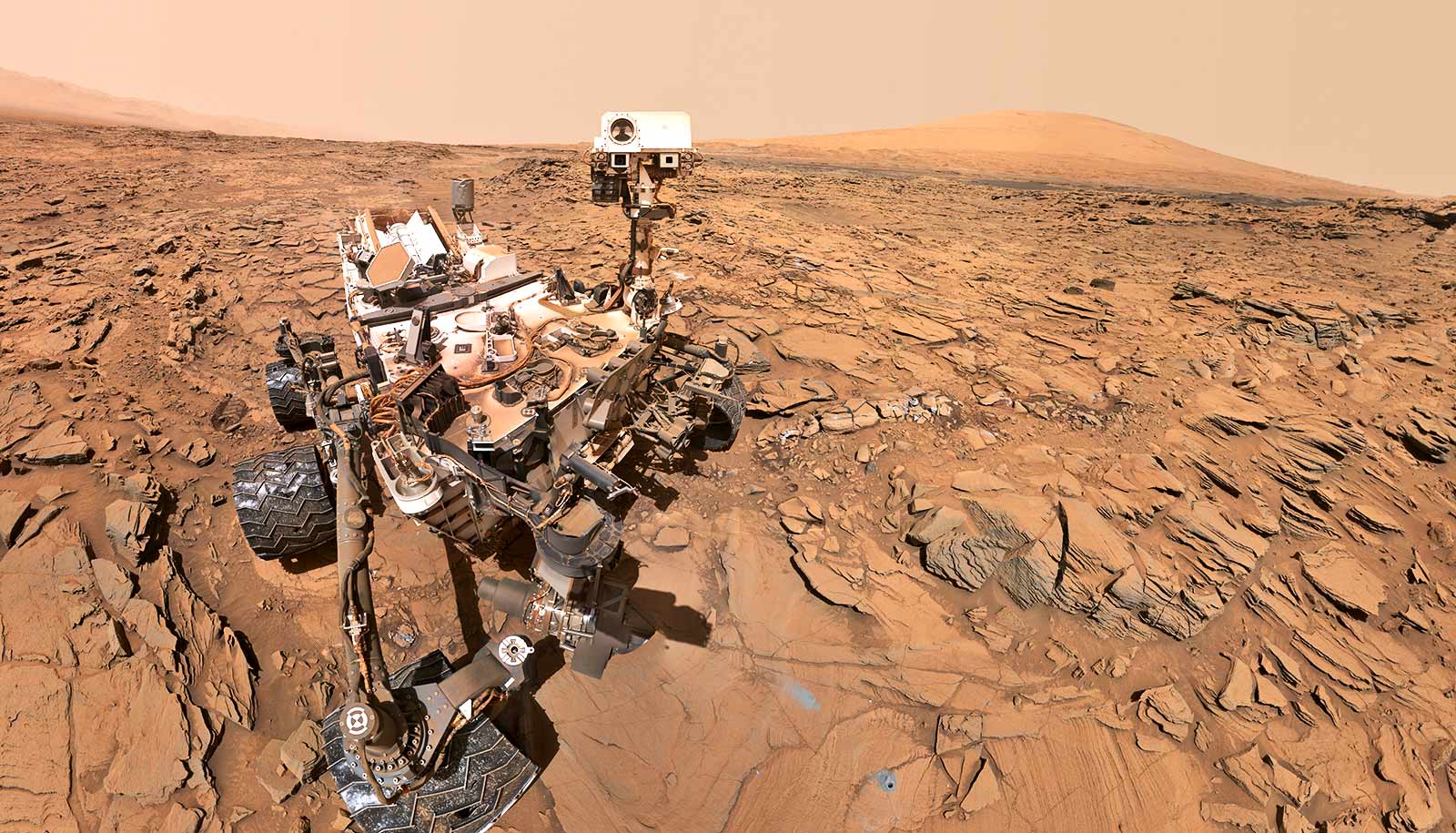

Designed to travel 1,100 yards and run for 90 Martian sols (days that are 39 minutes longer than Earth days), before the dust storm hit, the golf-cart size rover had roamed more than 28 miles and logged more than 5,000 sols.

Hours after landing in Eagle Crater, Opportunity relayed panoramic images back to Earth. When researchers noted a bedrock outcrop, the rover examined it for a first mission.

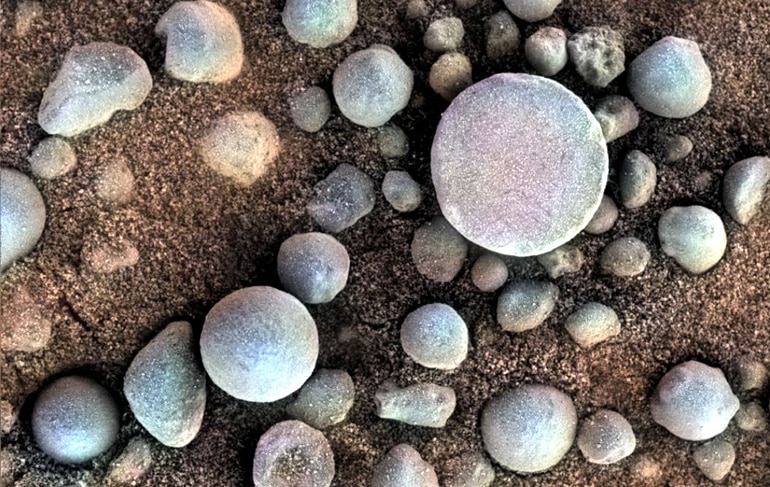

“…those ‘blueberries’ are a strong indicator that this place once contained water.”

“The thing about an outcrop is its geologic truth…it is the story of what happened in that place,” Squyres says. “There was a story waiting for us.”

There, researchers found “blueberries.”

“When we drove off the lander, we saw something very strange – there was a lot of sand and gravel. Lots of gravel…grains of gravel that looked awfully round,” Squyres says. Using the rover’s microscope, the scientists found the area “littered with an uncountable number of round things, they were scattered everywhere.”

“We had no clue what they were…initially.” The scientists knew that Meridiani Planum likely contained the mineral hematite and eventually realized that the hard, gravel-like spherules were “concretions” made of hematite and formed in the sedimentary rock when water was present.

“It turns out that those blueberries are a strong indicator that this place once contained water,” he says.

‘An honorable end’

Late last spring, as Opportunity hunkered down in Perseverance Valley on the western rim of Endeavour Crater, a gigantic Martian dust storm began to envelop a large portion of the planet.

“The payoff has been immensely greater than anything ever imagined in our wildest dreams.”

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter first detected the storm May 30. On June 10, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory received a transmission from Opportunity, indicating that the craft had enough battery charge then to enable communication. But scientists have heard nothing since.

By June 20, the dust storm blotted out the sun and entirely blanketed Mars. The storm abated in late July, and engineers tried in vain to reach Opportunity through early February 2019. But, it never responded.

“When I saw that the storm had gone global, I thought this could be it,” says Squyres, explaining that Opportunity was a solar-powered vehicle and needed the sun for energy.

“To have Opportunity—designed for 90 days—taken out after fourteen and a half years by one of the most ferocious dust storms to hit the planet in decades, you have got to feel pretty good about it. It was an honorable end, and it came a whole lot later than any of us expected.”

Both rovers gathered a lot of science, Squyres says.

“It’s mind boggling to me. If you had told me around the time that we landed that Spirit and Opportunity were going to each accomplish one-quarter or even one-tenth of what they ultimately did, I would have been thrilled.

“It’s because of the longevity of the vehicles…that Mars just kept giving us more stuff. The payoff has been immensely greater than anything ever imagined in our wildest dreams.”

Source: Cornell University