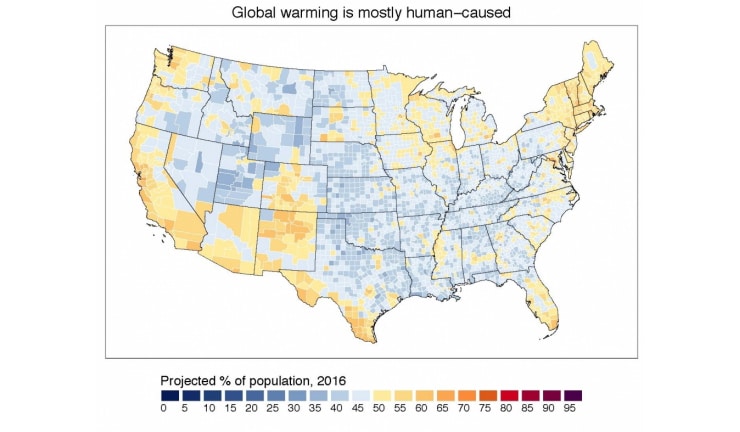

A new detailed, easily navigable opinion map clarifies what people in each county, city, and even congressional district in the United States believe about climate change.

A vast majority of Americans—70 percent, according to recent research—think global warming is indeed happening. That’s encouraging for climate scientists, but the numbers don’t paint a complete picture.

“The impetus for the project was that much of our understanding of the distribution and dynamics of public belief ends up relying on national surveys, and sometimes state polls, but we don’t really have a good understanding of the variation in beliefs and opinions at a local scale,” says Matto Mildenberger, an assistant professor of political science at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “These smaller political geographies are relevant for both political decision-making around climate change and adaptation and policy planning.”

Mildenberger is a member of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication that collected data and created the the Yale Climate Opinion Maps that detail climate energy beliefs at every level—from the national down to the hyper-local.

They designed the maps to effectively detail public perception of the issues surrounding global warming and climate change. While they could benefit policymakers, they were not developed with a single audience in mind, Mildenberger says.

“There are a number of audiences, including a big research audience. We see our role not as being advocates, but as providing objective information using the best possible quantitative techniques on the distribution of this opinion.” The data is available for anyone to download.

Data for the Yale Climate Opinion Maps came from a large national survey of more than 18,000 people that asked respondents multiple questions about their climate beliefs, including risk perceptions (i.e., how worried they were about the potential harm global warming could cause), their support for different policies (such as renewable energy and regulating carbon dioxide omissions), and even their common behaviors (whether they discussed global warming on a regular basis, for example).

The map tool allows the aggregated responses to each question to be broken down by metro area, county, and even congressional district. An examination of the data shows some trends.

“In working with this data, I found the sense that there was stronger support for a number of climate policy responses than I might have expected in a broader variety of places,” Mildenberger says.

“It allows us to have a more nuanced understanding of how the US is divided on this issue, and where there might be support for various mitigation and adaptation measures to protect Americans from dangerous human-caused climate change.”

Nearly all scientists believe climate change is real

Careful analysis of the mapping tool could be beneficial to politicians wondering whether a bill about carbon emissions or climate policy might have support in a given geographic area. “In some sense, the data can help us to understand the degree to which there is a disconnect between public climate policy preferences and the representation of those preferences in Congress,” he explains.

The maps show that many politicians likely would have the support they needed to pass climate protection measures in their districts. “I think the data highlights the fact that there is substantial heterogeneity in climate beliefs and energy beliefs across the country,” Mildenberger says.

“There are some policies and some opinions that are much more widespread in their distribution than popular media or conventional wisdom suggests. Even in this highly polarized environment, there are still some policies where we see majority support in every congressional district.”

Politics still drive how Americans view climate change

One major takeaway is that many Americans feel removed from climate change, both in time and distance.

“Looking at the maps, we can see that climate change is still perceived by many Americans as distant,” Mildenberger says. “We should expect that people’s perceptions and opinions of the impact of climate change on their lives would have a spatially resolved dimension.

“Hopefully, that’s a signal that this dataset and this work will slowly pick up over time as different communities become more engaged in the issue.”

Source: UC Santa Barbara