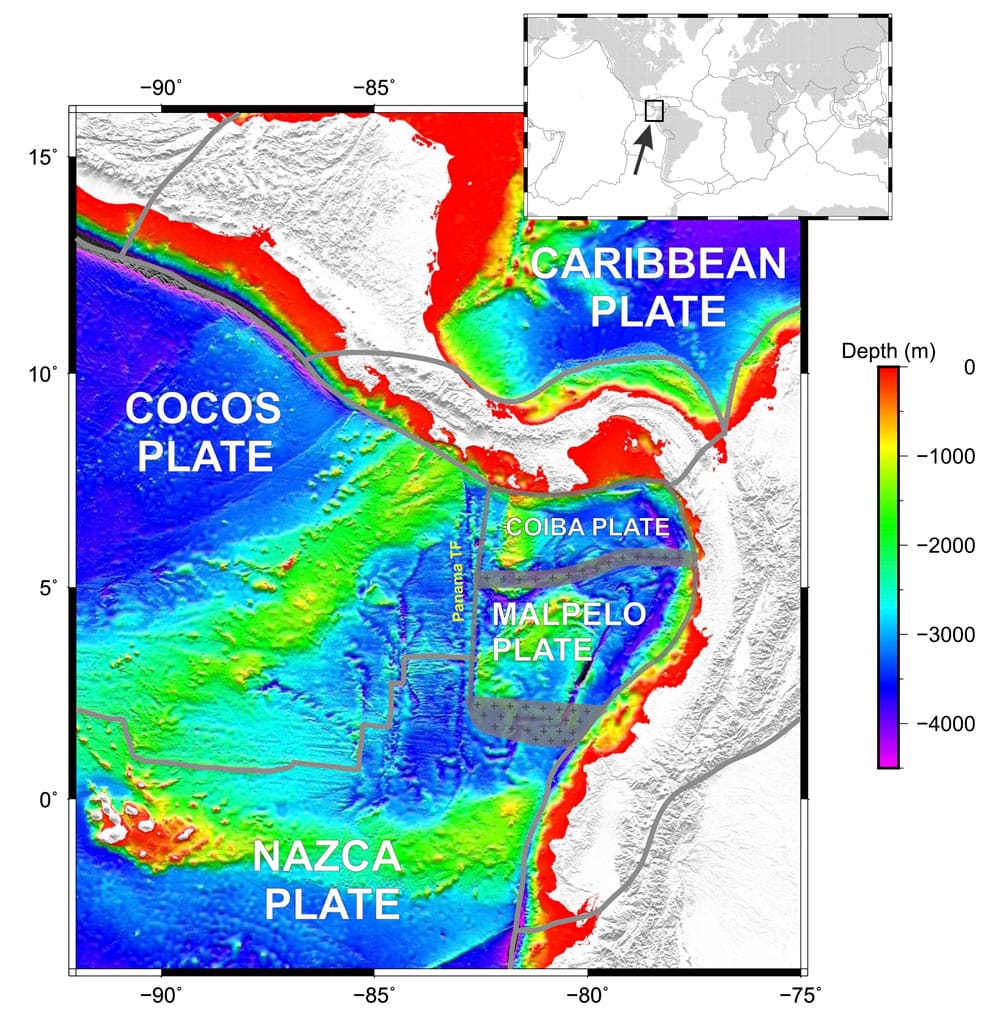

Scientists discovered a microplate, which they call “Malpelo,” while analyzing the junction of three other plates in the eastern Pacific Ocean. It lies off the west coast of Ecuador.

The Malpelo Plate, named for an island and an underwater ridge it contains, is the 57th plate to be discovered and the first in nearly a decade, say the researchers led by Rice University geophysicist Richard Gordon. They are sure there are more to be found.

How do geologists discover a plate? In this case, they carefully studied the movements of other plates and their evolving relationships to one another as the plates move at a rate of millimeters to centimeters per year.

The Pacific lithospheric plate that roughly defines the volcanic Ring of Fire is one of about 10 major rigid tectonic plates that float and move atop Earth’s mantle, which behaves like a fluid over geologic time. Interactions at the edges of the moving plates account for most earthquakes experienced on the planet. There are many small plates that fill the gaps between the big ones, and the Pacific Plate meets two of those smaller plates, the Cocos and Nazca, west of the Galapagos Islands.

One way to judge how plates move is to study plate-motion circuits, which quantify how the rotation speed of each object in a group (its angular velocity) affects all the others. Rates of seafloor spreading determined from marine magnetic anomalies combined with the angles at which the plates slide by each other over time tells scientists how fast the plates are turning.

“When you add up the angular velocities of these three plates, they ought to sum to zero,” Gordon says. “In this case, the velocity doesn’t sum to zero at all. It sums to 15 millimeters a year, which is huge.”

That made the Pacific-Cocos-Nazca circuit a misfit, which meant at least one other plate in the vicinity had to make up the difference. Misfits are a cause for concern—and a clue.

Knowing the numbers were amiss, the researchers drew upon a Columbia University database of extensive multibeam sonar soundings west of Ecuador and Colombia to identify a previously unknown plate boundary between the Galapagos Islands and the coast.

Previous researchers had assumed most of the region east of the known Panama transform fault was part of the Nazca plate, but the researchers determined it moves independently. “If this is moving in a different direction, then this is not the Nazca plate,” Gordon says. “We realized this is a different plate and it’s moving relative to the Nazca.”

Evidence for the Malpelo plate came with the researchers’ identification of a diffuse plate boundary that runs from the Panama Transform Fault eastward to where the diffuse plate boundary intersects a deep oceanic trench just offshore of Ecuador and Colombia.

“A diffuse boundary is best described as a series of many small, hard-to-spot faults rather than a ridge or transform fault that sharply defines the boundary of two plates,” Gordon says. “Because earthquakes along diffuse boundaries tend to be small and less frequent than along transform faults, there was little information in the seismic record to indicate this one’s presence.”

“With the Malpelo accounted for, the new circuit still doesn’t close to zero and the shrinking Pacific Plate isn’t enough to account for the difference either,” says lead author Tuo Zhang. “The nonclosure around this triple junction goes down—not to zero, but only to 10 or 11 millimeters a year.

“Since we’re trying to understand global deformation, we need to understand where the rest of that velocity is going,” he says. “So we think there’s another plate we’re missing.”

Coauthors Jay Mishra and Chengzu Wang contributed to the study in Geophysical Research Letters.

The National Science Foundation supported the research.

Source: Rice University