Genomic differences related to the immune system may play a key role in the early development of lung cancer, according to new research.

The finding reveals potential for developing new therapeutics that could boost immune activity to prevent or halt progression of the disease, says senior author Avrum Spira, director of the Johnson & Johnson Innovation Lung Cancer Center at Boston University and the global head of the Johnson & Johnson Lung Cancer Initiative.

He says that researchers can detect the newly identified genomic differences in normal airway tissue before any precancerous activity begins, which could potentially help physicians screen and monitor smokers who are at the highest risk of lung cancer.

Spira has been working for several years with collaborators on a Precancer Genomic Atlas project to identify early cellular and molecular changes that lead to invasive lung cancer.

“Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide, because the disease is typically diagnosed in its later stages,” says William N. Hait, global head of Johnson & Johnson External Innovation in a press release about the findings.

More people die of lung cancer than from colon, breast, and prostate cancers combined—in the US alone, lung cancer kills about 143,000 people each year. Worldwide, the number of people with the disease remains high and is growing in certain regions, and among women. In China, for example, 730,000 new cases of lung cancer were reported in 2015 and the number is expected to rise.

“The lung undergoes many changes prior to the development of [full-blown] lung cancer, so we have an opportunity to leverage those changes to both identify people at high risk for lung cancer and to intercept the disease process,” says Jennifer Beane, the lead and corresponding author of the Nature Communications study, and a Boston University School of Medicine assistant professor of computational medicine.

The new findings have identified four different genomic subtypes among current and former cigarette smokers who develop precancerous lesions. In people with the most problematic subtype, their immune response is impaired, says Spira, a professor of medicine, pathology, and bioinformatics and professor in health care entrepreneurship.

“That’s one of the things that tumors do—prevent the immune system from attacking them. We think precancer cells might do that as well,” says Spira. “This opens up the opportunity to come in and find a way to train the immune system to eradicate those lesions.”

Any drug that could arrest or prevent lung cancer from developing in smokers would be the first of its kind. “There is nothing [for lung cancer] like there is aspirin for colorectal cancer or statins for cardiovascular disease,” he says.

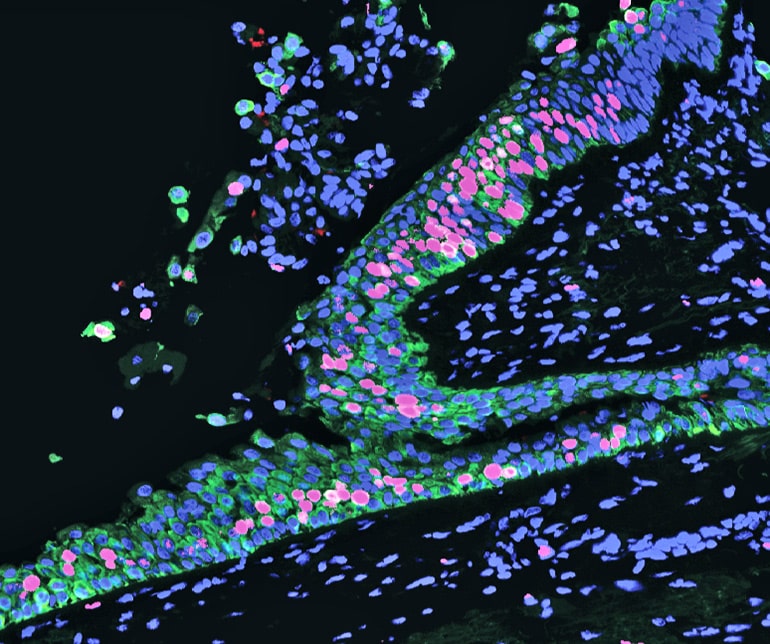

In the study, Beane, Spira, and colleagues used bronchoscopes to take biopsies of precancerous lung lesions in current and former smokers, following the study participants over several years to see if their lesions progressed toward lung cancer or not. They identified biological changes within the lesions that indicated a higher risk of progression and showed that those lesions had reduced activity of genes related to certain kinds of immune cells.

“This is an example where academia does the very basic discovery science—finding patients that have these early precancer lesions, biopsying them, and doing very deep molecular profiling, and the bioinformatics analysis,” says Spira.

Then, from those academic findings, “industry can look at the data and figure out how to develop a therapeutic that will leverage that insight, that would reactivate the immune system to intercept the precancerous lesions from progressing to invasive lung cancer.”

In addition to its other findings, the new study suggests that researchers could detect changes in aggressive precancerous lesions by “brushing,” using a flexible brush to gather cells from the airway through the catheter of a bronchoscope, which is a much less invasive procedure than a traditional lung or airway biopsy.

“Normal-appearing cells in the airway can still show you the genomic signature,” says Beane. “It’s early days, but maybe one day [we] could develop a simpler test to find someone who is incubating a lung cancer and [we’d] know who to treat to intercept lung cancer.”

Additional researchers from Boston University School of Medicine; the University of California, Los Angeles; the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, in Buffalo, NY; and Janssen Research & Development. Support for this study came, in part, from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health; Stand Up To Cancer, LUNGevity, American Lung Association Lung Force; and Janssen Research & Development, LLC.

Janssen Research & Development, LLC, one of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson, and Boston University developed the Precancer Genomic Atlas. It has received additional funding from Stand Up To Cancer-LUNGevity-American Lung Association Lung Cancer Interception Dream Team, the National Cancer Institute, and the new Translational Research Alliance between Boston University and the Lung Cancer Initiative at J&J.

Source: Boston University