Researchers have discovered a “remarkably complete” cranium of a 3.8-million-year-old early human ancestor.

Working for the past 15 years at the Woranso-Mille paleontological site in the Afar region of Ethiopia, the team discovered the cranium (MRD-VP-1/1), here referred to as “MRD,” in February 2016. In the years following the discovery, paleoanthropologists conducted extensive analyses of MRD, while project geologists worked on determining the specimen’s age and context.

The 3.8-million-year-old fossil cranium (MRD) represents a time interval between 4.1 and 3.6 million years ago when early human ancestor fossils are extremely rare, especially outside the Woranso-Mille area.

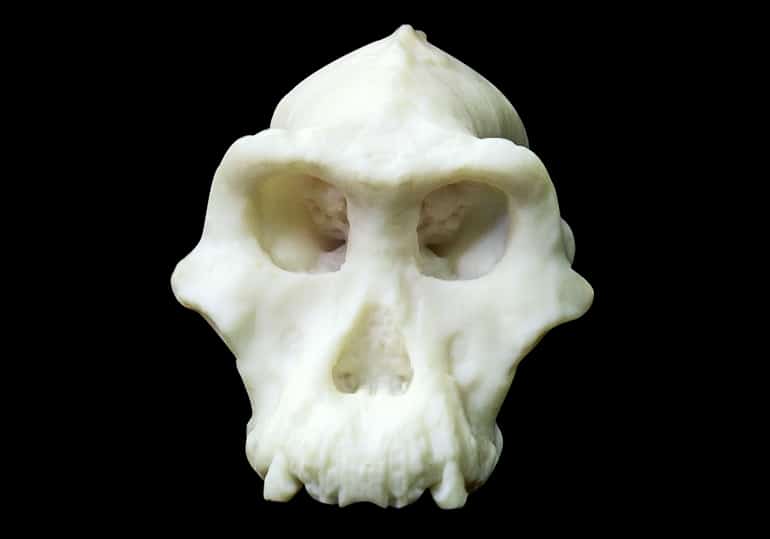

MRD offers new information on the overall craniofacial morphology of Australopithecus anamensis, a species widely accepted as the ancestor of Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis.

It also shows that Lucy’s species and its hypothesized ancestor, A. anamensis, coexisted for approximately 100,000 years, challenging previous assumptions of a linear transition between these two early human ancestors.

The discovery is reported in two papers in Nature.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes when I spotted the rest of the cranium. It was a eureka moment and a dream come true.”

“This is a game changer in our understanding of human evolution during the Pliocene,” says Yohannes Haile-Selassie, an adjunct professor at Case Western Reserve University and curator at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

The Woranso-Mille project has conducted field research in the central Afar region of Ethiopia since 2004. The project has collected more than 12,600 fossil specimens representing about 85 mammalian species. The fossil collection includes about 230 fossil hominin specimens dating to between >3.8 and ~3.0 million years ago.

Ali Bereino (a local Afar worker) found the first piece of MRD, the upper jaw, at a locality known as Miro Dora, Mille District of the Afar Regional State of Ethiopia. Miro Dora is about 550 km (around 342 miles) northeast of the capital, Addis Ababa, and 55 km (34 miles) north of Hadar (“Lucy’s” site). The specimen was exposed on the surface, and further investigation of the area led to the recovery of the rest of the cranium.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes when I spotted the rest of the cranium. It was a eureka moment and a dream come true,” Haile-Selassie says.

In a companion paper published in the same issue of Nature, Beverly Saylor of Case Western Reserve University and her colleagues reported the age of the fossil as 3.8 million years by dating minerals in layers of volcanic rocks nearby. They mapped the dated levels to the fossil site using field observations and the chemistry and magnetic properties of rock layers.

Saylor and her colleagues combined the field observations with analysis of microscopic biological remains to reconstruct the landscape, vegetation, and hydrology where MRD died.

Environmental clues

Researchers found MRD in the sandy deposits of a delta where a river entered a lake. The river likely originated in the highlands of the Ethiopian plateau while the lake developed at lower elevations, where rift activity caused the Earth surface to stretch and thin, creating the lowlands of the Afar region.

Debris flows and volcanic ejecta occasionally descended into the otherwise quiet lake, which was ultimately buried by basalt lava flows. This kind of volcanic activity and dramatic landscape change is common in rift settings.

“Incredible exposures and the volcanic layers that episodically blanketed the land surface and lake floor allowed us to map out this varied landscape and how it changed over time,” Saylor says.

Naomi Levin, an associate professor in the earth and environmental science department at the University of Michigan and coauthor of the paper, coordinated environmental reconstructions at the site with an interdisciplinary team from several institutions.

“MRD lived near a large lake in a region that was dry. We’re eager to conduct more work in these deposits to understand the environment of the MRD specimen, the relationship to climate change, and how it affected human evolution, if at all,” Levin says.

Fossil pollen grains and chemical remains of fossil plants and algae that are preserved in the lake and delta sediments provide clues about the ancient environmental conditions. Specifically, they indicate that the lake near where MRD finally rested was likely salty at times and that the watershed of the lake was mostly dry but that there were also forested areas on the shores of the delta or along the side of the river that fed the delta and lake system.

“The existence of a large lake is clear from field observations of sediments, but it’s the preservation and chemical composition of microscopic parts of plants and algae that helped us figure out that the surrounding watershed was dry,” Levin says.

Levin also codirects an isotope geochemistry lab that conducts geological analyses using carbon and oxygen isotopes.

“While it can be common to have a large lake in a dry climate in rift settings, just the presence of large lakes in the geologic record can be used to infer wet climate intervals,” she says. “So it was key that we drew on the expertise of our interdisciplinary team to figure out the broader climate context of this lake.”

Cranial mash-up

Here are the significant aspects of the discovery:

- Australopithecus anamensis and its descendant species, the well-known Australopithecus afarensis, coexisted for a period of at least 100,000 years. This finding contradicts the long-held notion of an anagenetic relationship between these two taxa, whereby one species disappears only by giving rise to a new species in a linear fashion.

- Australopithecus anamensis is the oldest known member of the genus Australopithecus. The species was previously only known through teeth and jaw fragments, all dated to between 4.2 and 3.9 million years ago. The similarities between the preserved dentition of the 3.8-million-year-old MRD and the previously known teeth and jaw fragments of A. anamensis led to a positive identification of MRD as a member of A. anamensis. Additionally, due to the cranium’s rare near-complete state, the researchers identified never-before-seen facial features in the species.

- “MRD has a mix of primitive and derived facial and cranial features that I didn’t expect to see on a single individual,” Haile-Selassie says. Coauthor Stephanie Melillo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany adds, “A. anamensis was already a species that we knew quite a bit about, but this is the first cranium of the species ever discovered. It is good to finally be able to put a face to the name.” Some characteristics were shared with its descendant species, Australopithecus afarensis, while others differed significantly and had more in common with those of even older and more primitive early human ancestor groups, such as Ardipithecus and Sahelanthropus.

- The distinct differences between the 3.8-million-year-old MRD specimen and a previously unassigned 3.9-million-year-old hominin cranium fragment—commonly known as the Belohdelie frontal and discovered in the Middle Awash of Ethiopia by a team of paleontologists in 1981—also proved significant. The preserved features of the Belohdelie frontal differed from those of MRD but were significantly similar to those of the known cranial specimens of Lucy’s species. As a result, the new study confirms that the Belohdelie frontal belonged to an individual of Lucy’s species. This identification extends the earliest record of Australopithecus afarensis back to 3.9 million years ago, indicating a period of at least 100,000 years’ overlap with its ancestor, Australopithecus anamensis.

- The 3.8-million-year-old MRD specimen was buried in a river delta on the margin of a lake that formed in an actively rifted landscape with steep hillsides and volcanic eruptions that blanketed the land surface with ash and lava. There were forested areas on the shores of the delta or along the edges of the river that flowed into the delta and lake system, but the watershed that fed the river, delta, and lake system was mostly dry with few trees.

Additional project researchers are from Penn State; the University of Bologna; Universitat de Barcelona; Berkeley Geochronology Center; Addis Ababa University; Franklin and Marshall College, University of Southern California; and Aix-Marseille University.

Source: University of Michigan via Patrick Evans for Cleveland Museum of Natural History