A type of beetle that can regulate its body temperature in some of the hottest places on Earth inspired a new cooling material that doesn’t need energy, researchers say.

The work could have major implications for cooling everything from buildings to electronic devices in an environmentally friendly manner.

“Anywhere that needs cooling, this can help.”

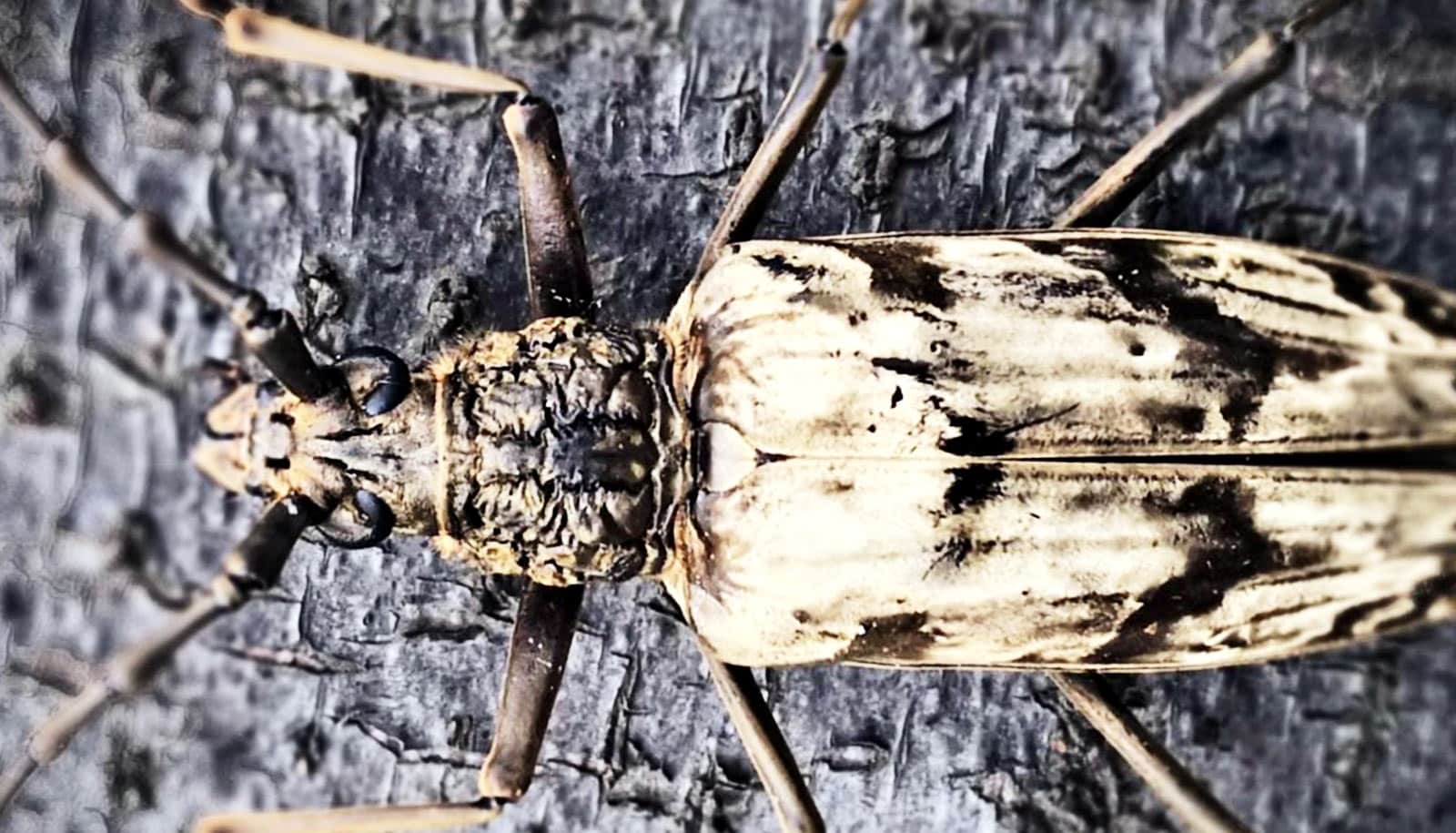

New information about a species of longicorn beetle that can cool its body enough to survive in volcanic areas in Southeast Asia led to researchers to create a photonic film based on the beetle’s wing structure. They used common, flexible materials that are mechanically strong and can be manufactured on a large scale.

The film passively cools, meaning it doesn’t take up energy like the systems we use to keep temperatures down in our cars and buildings.

The findings appear in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Anywhere that needs cooling, this can help,” says Yuebing Zheng, an associate professor in the mechanical engineering department at the University of Texas at Austin. “Refrigerators, air conditioners, and other methods consume large amounts of energy, but this is cooling by itself.”

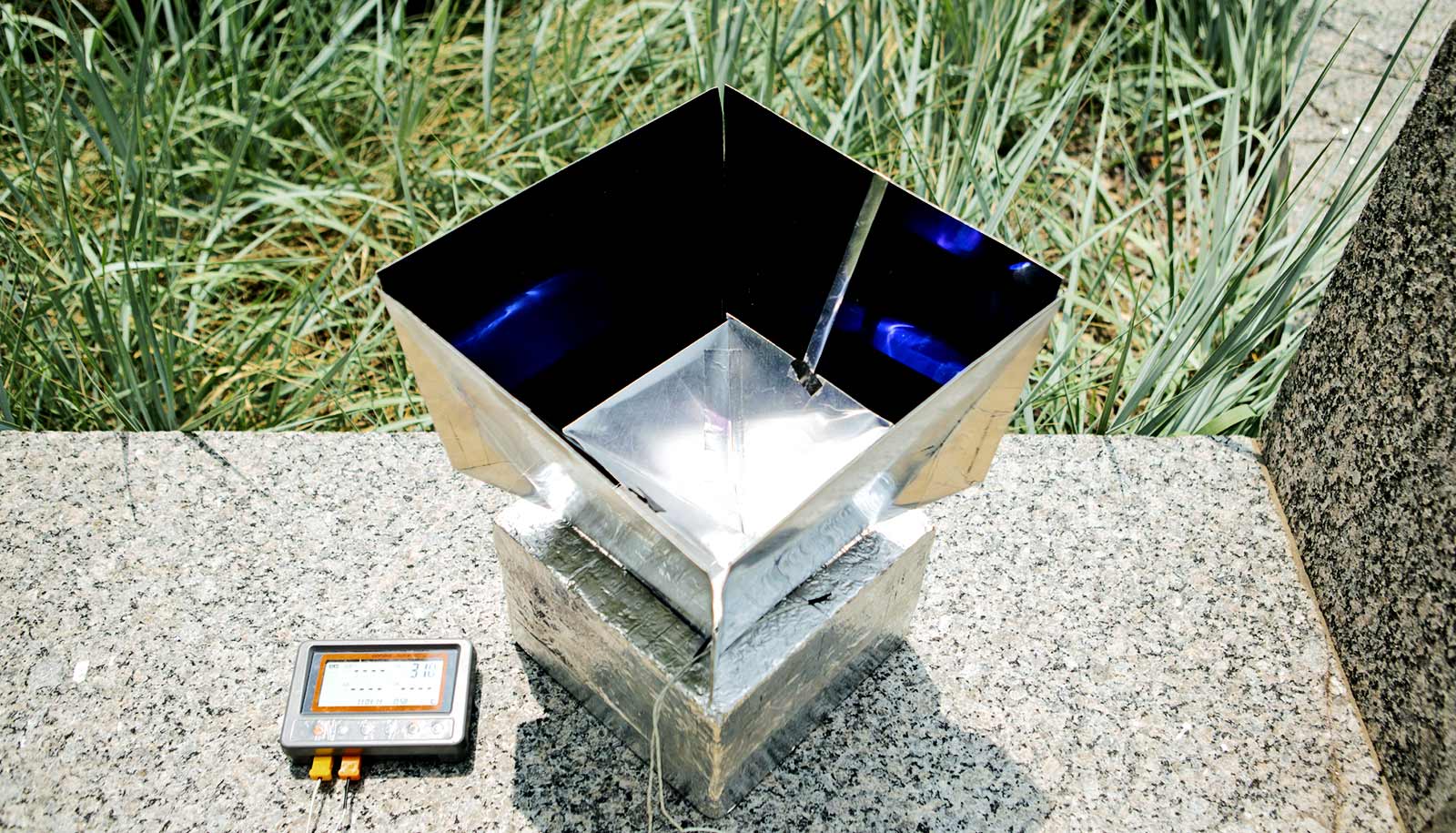

The team found that its film reduced temperatures of items in direct sunlight by as much as 5.1 degrees Celsius, more than 9 degrees Fahrenheit.

Lots of uses for the cooling material

The film, which would work as a coating on top of objects, could have a wide array of uses. It could be put on top of windows in office and apartment buildings to reflect sunlight and keep energy bills down. It could protect solar panels from being degraded by constant sunlight exposure. It could be wrapped around cars to keep them cool while parked. And it could be a key ingredient in novel cooling fabrics, wearables, and personal electronics.

The US Energy Information Administration projects a significant jump in air conditioning consumption by 2050—a 59% growth in the residential sector and a 17% increase in commercial use. As the need for more cooling rises, so does the necessity for a new solution that doesn’t consume mass amounts of energy or put a strain on the environment.

The cooling prowess of the beetle was previously known, but what made it so effective at regulating its temperature remained a mystery. The team found that the triangular “fluffs” on its wings play an important role, reflecting sunlight while helping shed internal body heat at the same time.

Longicorn beetles, also known as longhorn beetles, stand out because of their long antennae, sometimes three times the length of the rest of their bodies. There are more than 26,000 species of longicorn beetles.

This research focuses on a specific species of the beetle, Neocerambyx Gigas. It can survive in scorching hot climates near active volcanoes in Thailand and Indonesia, where summer temperatures frequently top 40 degrees Celsius (105 degrees Fahrenheit), and the ground heats up to 70 C (158 F). When it gets hot, the beetles remain still and stop foraging to avoid taking on any excess heat from movement.

Avoiding manufacturing problems

The film the team created is made of PDMS, a flexible, widely used polymer, along with some high throughput ceramic particles.

Because of the common materials used and the simple process for manufacturing the film, known as micro-stamping, Zheng believes the project will succeed where some other research seeking to replicate biological effects has failed.

“A lot of time, mimicking the biology doesn’t work at a larger scale because of high costs and stringent manufacturing requirements,” Zheng says.

Going forward, the research team is working to further optimize the manufacturing process for large-scale production. They will also seek commercialization opportunities in several areas, including energy-efficient buildings, water cooling systems, thermal fabrics, desert dew water harvesting devices, and supplemental cooling systems for power plants.

Additional researchers from UT Austin, Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China, and KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden contributed to the work.

Source: UT Austin