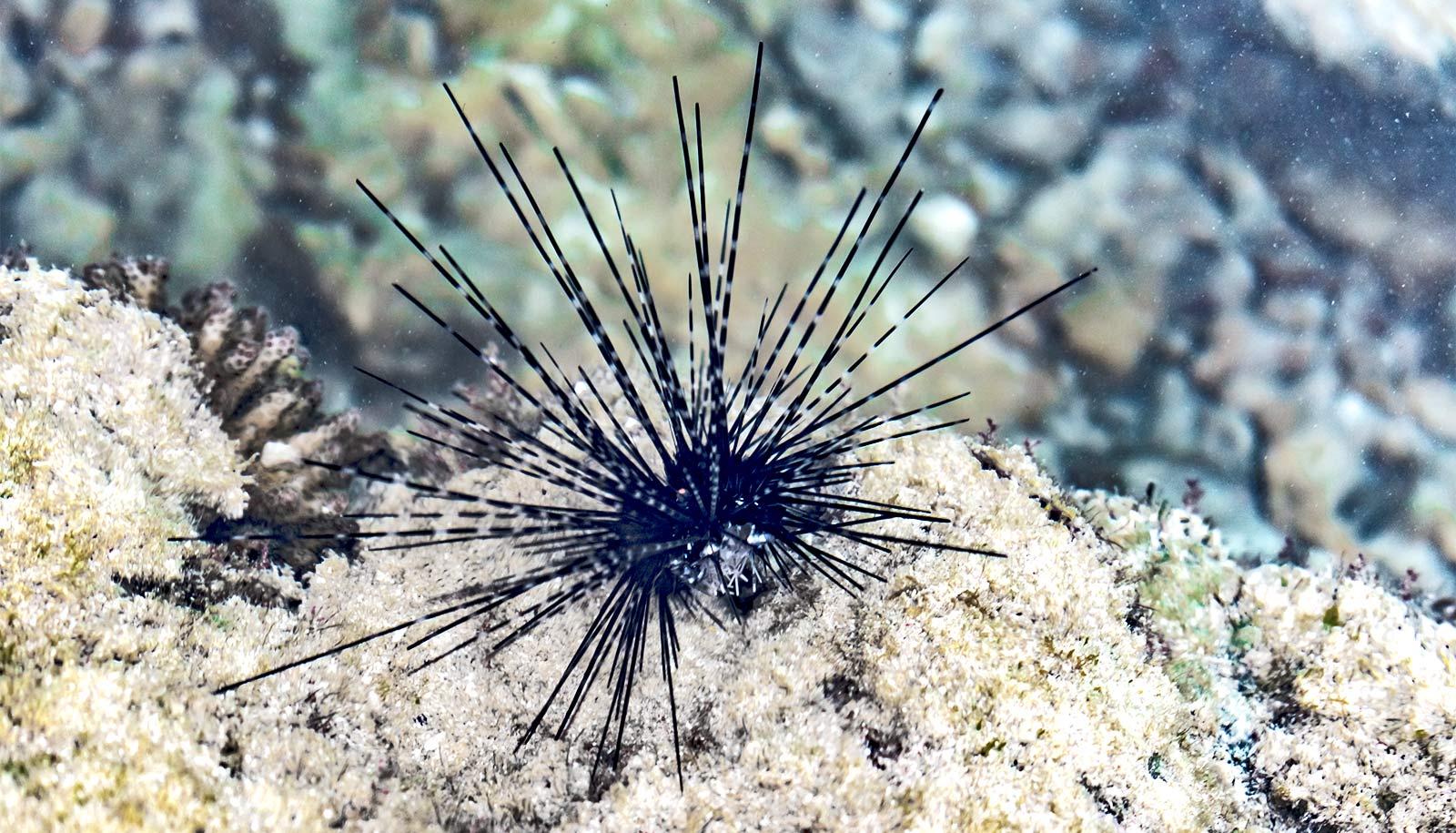

Scientists are trying to raise as many long-spined sea urchins in the lab as possible.

The urchins are known as “the lawn mowers of the reefs” because they eat algae that could otherwise smother reef ecosystems and kill corals.

Aaron Pilnick, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Florida Tropical Aquaculture Lab (TAL), led a new study that identifies substrates that help long-spined sea urchins—scientifically known as diadema—grow from larvae to juveniles in a lab setting. A substrate is the surface on the sea floor on which an organism lives or obtains its nourishment.

Researchers found that sea urchin larvae grew into juvenile sea urchins on two types of algae commonly found on the floor of Caribbean coral reefs. They also found that the characteristics of a substrate, such as a rough texture, are important.

To reach their findings, the scientists relied on the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission to bring adult urchins from the Florida Keys to the Florida Aquarium Conservation Campus. There, researchers induced the urchins to spawn in captivity.

Larvae grew in a highly specialized, 10-gallon fish tank for about 40 days. Then, scientists used a microscope to document the size, shape, and structure of live specimens during the final stages of larval development. They then transferred the larvae to petri dishes, containing seawater and various substrates and recorded if they became juvenile sea urchins.

Restoring the long-spined sea urchin is critical because in the early 1980s, disease nearly wiped out the species. That die-off almost immediately led to algae overgrowing reefs.

“We are trying to restore these vital ecosystems by growing corals in ocean nurseries and planting them back to areas where they used to thrive. However, these reefs also need more urchins to protect corals from algae,” says Pilnick, who led the research while a doctoral student in the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS) College of Agricultural and Life Sciences.

To restore sea urchins, it’s important to know their growth patterns. Urchin larvae float and swim around the ocean until they find a place on the sea floor to attach and transform into a juvenile sea urchin.

This process, called “settlement,” is similar to how a pupa turns into a butterfly. By developing the ability to grow this species, scientists can study settlement in the lab and infer certain things about its ecology.

Now that scientists have identified conditions for long-spined sea urchins to grow from larvae to juveniles, they’re studying how to get them to mature to adulthood, says coauthor Josh Patterson, an associate professor of restoration aquaculture in the School of Forest, Fisheries, & Geomatics Sciences, Pilnick’s supervisor, and a Florida Sea Grant-affiliated researcher.

“For many marine animals, the transition from larvae to adults is a critical part of the life cycle. This research is groundbreaking because it’s the first time this transition has been investigated in this important species,” Patterson says.

The study is published in the journal Marine Biology.

Source: University of Florida