Researchers have identified the oldest-known, definitive members of an evolutionary group that includes all living lizards and their closest extinct relatives.

The two new species, Eoscincus ornatus and Microteras borealis, fill important gaps in the fossil record and offer tantalizing clues about the complexity and geographic distribution of lizard evolution.

The new lizard “kings” are described in a study published in Nature Communications.

“This helps us time out the ages of the major living lizard and snake groups, as well as when their key anatomical features originated,” says first author Chase Brownstein, a senior at Yale University who collaborated with Jacques Gauthier, a professor of earth and planetary sciences and Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar, an associate professor of earth and planetary sciences and an associate curator at the Peabody Museum.

Lizard evolution is known to cover more than 250 million years of Earth’s history—yet there are few surviving fossils from the first half of that period. This dearth of evidence has left researchers with unresolved questions about how and when lizards developed or discarded specific physical features.

But new analytical approaches and technologies are allowing paleontologists to gain insights.

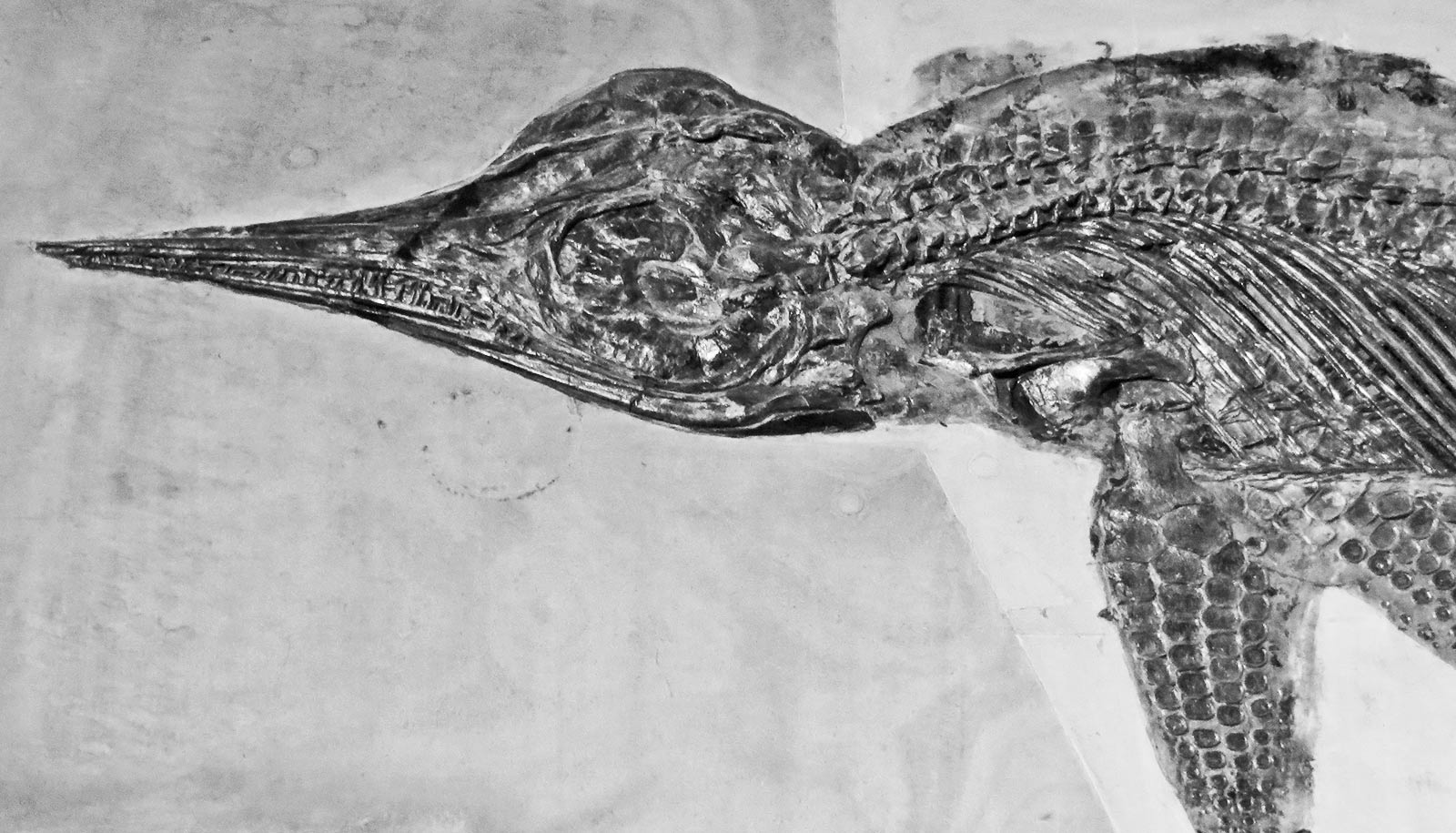

For the new study, Brownstein and his colleagues used high-resolution, computed tomography (CT) scans to create 3D images of two previously discovered lizard skulls from the western US. An analysis of the scans revealed that the skulls—which are 145 million years old—belong to two new lizard species.

One of the new species, Eoscincus ornatus, came from what is now Dinosaur National Monument in Utah. Its skull has at least one feature that is absent in nearly all modern lizards: two rows of teeth on a palate bone called the vomer. The other new species, Microteras borealis, came from what is now Como Bluff Quarry in Wyoming.

In addition to being the oldest-known lizards that fit firmly within the main line of lizards (known as squamata) Eoscincus ornatus and Microteras borealis share physical characteristics with other species found in Eurasia. This implies a wide, global distribution for major groups of squamates even in ancient times, the researchers say.

“When put into a larger ecological context, the new species demonstrate that major living lizard groups started to assemble their body plans quite early,” Brownstein says. “They developed key physical features at a time when another group of lizard relatives—rhynchocephalians, now represented by only the tuatara of New Zealand—was more dominant.”

Dalton Meyer, a graduate student in earth and planetary sciences, and former graduate student Matteo Fabbri, now at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago are coauthors of the study.

The National Science Foundation and the Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies funded the work.

Source: Yale University