A new bendable lithium-ion battery prototype continues delivering electricity even when cut into pieces, submerged in water, or struck with force.

“We are very encouraged by the feedback we are receiving,” says Jeffrey P. Maranchi, manager of the materials science program at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. “We are not that far away from testing in the field.”

As reported in Advanced Materials, the new battery type is a response to safety hazards associated with older lithium-ion battery cells, including those associated several years ago with reports of exploding hover board toys.

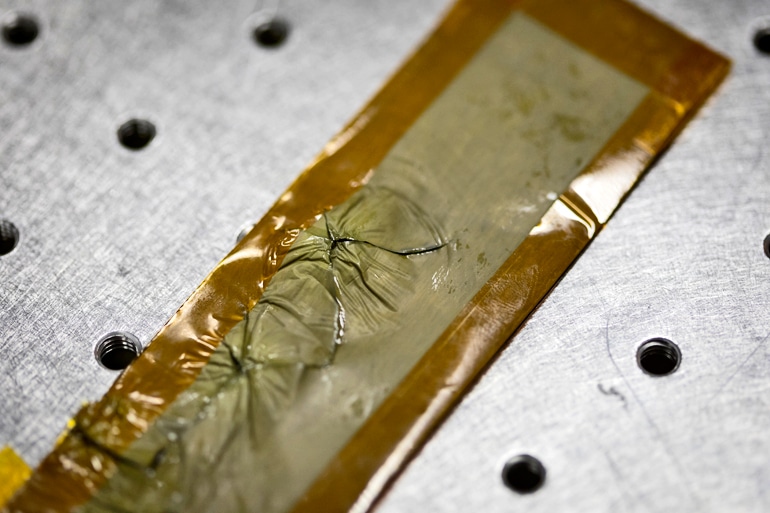

(Credit: Johns Hopkins APL)

Lithium-ion batteries are widely used in consumer electronics and military and aerospace systems, due to their energy and power performance. But the highly flammable, toxic, and moisture-sensitive nature of the electrolytes they contain limits the forms in which a lithium-ion battery can now be manufactured.

The work on the safer, more durable battery builds upon a new aqueous electrolyte referred to as “water-in-salt,” developed in 2015 by University of Maryland and Army Research Lab scientists.

This highly concentrated water-based electrolyte addresses the key issue associated with the use of water in lithium-ion batteries, the low electrochemical stability window of roughly 1.2 volts. By expanding this window to 3 volts, the water-in-salt enables much higher energy density aqueous lithium-ion batteries.

“By collaborating with APL, we are starting to transition this technology into novel battery architectures and demonstrate its practical true potential,” says corresponding author Chunsheng Wang, professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at the University of Maryland.

The team embedded the water-in-salt electrolyte in a polyvinyl alcohol polymer matrix, forming a gel polymer electrolyte. This GPE is even more stable than the liquid form, making possible a flexible battery that can be twisted and folded.

“What limits the form factor of current lithium-ion batteries is the flammable organic electrolytes,” says Kostas Gerasopoulos, an APL senior research scientist and principal investigator.

“To ensure safety, you need sufficient packaging and protective measures. When the water-in-salt electrolyte was introduced, I thought that making a stable polymer version would radically change the way that lithium-ion batteries are made and used.”

Defects actually give lithium-ion batteries a boost

The team has used the flexible Li-ion battery to produce electricity in open air with minimal packaging, using only some electronically insulating heat-resistant tape to keep the flexible substrate in place. In their demonstration, the battery powered a fan without causing any safety concerns.

While the battery was in operation, researchers cut it, immersed it in seawater, and subjected it to a battering in ballistic testing at an APL facility. The battery didn’t explode or catch fire—and continued to power the fan when damaged and exposed to air and water.

The safety of the new battery promises to be important not only in consumer devices, but also in military applications.

Cheap sodium battery works as well as pricey lithium

“Particularly for our military, with our warfighters exposed to extreme conditions and environments during their missions, the capability to maintain both safety and performance is unprecedented,” Gerasopoulos says.

“By making the batteries flexible and lighter compared to the devices currently used in the field, you can significantly decrease the burden to the warfighter,” adds Kang Xu, electrochemistry team leader and fellow at the Army Research Lab.

The Department of Energy and APL funded the research.

Source: Johns Hopkins University