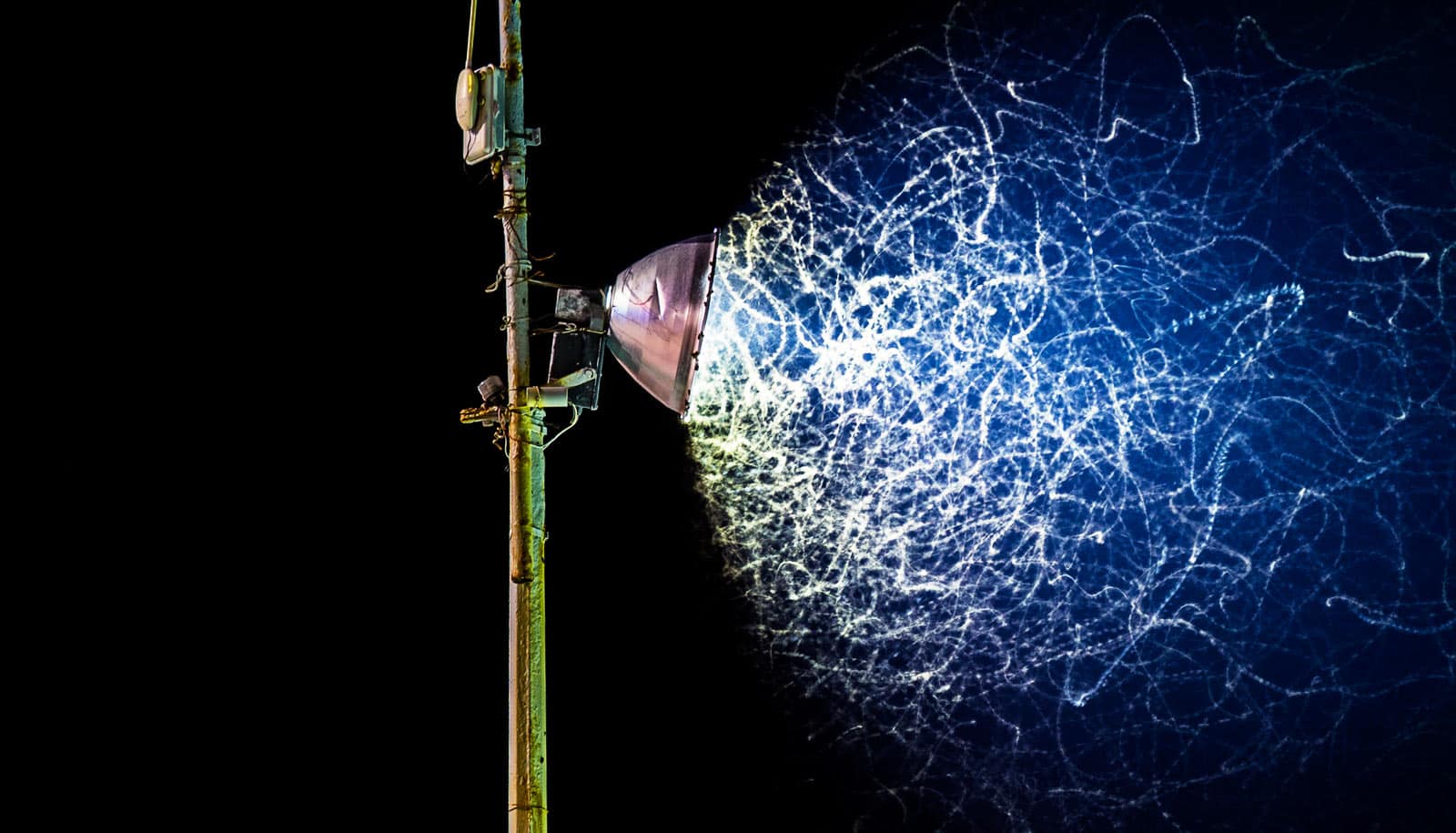

Exposure to light pollution may alter predator-prey dynamics between mule deer and cougars across the intermountain West, a region where night skyglow is an increasing environmental disturbance, researchers report.

The study is the first to assess the effects of light pollution on predator-prey interactions at a regional scale. It combines satellite-derived estimates of artificial night time lights with GPS location data from hundreds of radio-collared mule deer and cougars across the intermountain West.

The study found that:

- Mule deer living in light-polluted areas are drawn to artificial night time lighting, which is associated with green vegetation around homes.

- Cougars, also known as mountain lions and pumas, are able to successfully hunt within light-polluted areas by selecting the darkest spots on the landscape to make their kill.

- While mule deer that live in dark wildland locations are most active around dawn and dusk, those living around artificial night light forage throughout the day and are more active at night than wildland deer—especially during the summer.

The animal data used in the study were collected by state and federal wildlife agencies across the region. Collation of those records yielded what is believed to be the largest dataset on interactions between cougars and mule deer, two of the most ecologically and economically important large-mammal species in the West.

“Our findings illuminate some of the ways that changes in land use are creating a brighter world that impacts the biology and ecology of highly mobile mammalian species, including an apex carnivore,” says lead author Mark Ditmer, formerly a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability and now at Colorado State University.

Mule deer and cougars

The intermountain West spans nearly 400,000 square miles and is an ideal place to assess how varying light-pollution exposures influence the behavior of mule deer and cougars and their predator-prey dynamics.

Both species are widely distributed throughout the region—the mule deer is the cougar’s primary prey species—and the region presents a wide range of night time lighting conditions.

The intermountain West is home to some of the darkest night skies in the continental United States, as well as some of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas, including Las Vegas and Salt Lake City. Between the dark wildlands and the brightly illuminated cities is the wildland-urban interface, the rapidly expanding zone where homes and associated structures are built within forests and other types of undeveloped wildland vegetation.

For the study, researchers obtained detailed estimates of night time lighting sources from the NASA-NOAA Suomi polar-orbiting satellite. They collected GPS location data for 117 cougars and 486 mule deer from four states: Utah, Arizona, Nevada, and California. In addition, wildlife agencies provided locations of 1,562 sites where cougars successfully killed mule deer.

“This paper represents a massive undertaking, and to our knowledge this dataset is the largest ever compiled for these two species,” says senior author Neil Carter, a conservation ecologist at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability.

Deer in the arid West are attracted to the greenery in the backyards and parks of the wildland-urban interface. Predators follow them there, despite increased night time light levels that they would normally shun. Going into the study, the researchers suspected that light pollution within the wildland-urban interface could alter cougar-mule deer interactions in one of two ways.

Perhaps artificial night time light would create a shield that protects deer from predators and allows them to forage freely. Alternatively, cougars might exploit elevated deer densities within the wildland-urban interface, feasting on easy prey inside what scientists call an ecological trap.

Predator shield and ecological trap

Data from the study provides support for both the predator shield and ecological trap hypotheses, the researchers say. At certain times and locations within the wildland-urban interface, there is simply too much artificial light and/or human activity for cougars, creating a protective shield for deer.

An ecological trap occurs when an animal is misled, or trapped, into settling for apparently attractive but in fact low-quality habitat. In this particular case, mule deer are drawn to the greenery of the wildland-urban interface and may mistakenly perceive that the enhanced night time lighting creates a predator-free zone.

But the cougars are able to successfully hunt within the wildland-urban interface by carefully selecting the darkest spots on the landscape to make their kill, the study shows. In contrast, cougars living in dark wildland locations hunt in places where night time light levels are slightly higher than the surroundings, the researchers found.

“The intermountain West is the fastest-growing region of the US, and we anticipate that night light levels will dramatically increase in magnitude and across space,” Carter says. “These elevated levels of night light are likely to fundamentally alter a predator-prey system of ecological and management significance—both species are hunted extensively in this region and are economically and culturally important.”

Additional coauthors of the paper, published in Ecography, are from Utah State University, California Polytechnic University, Boise State University, the University of Minnesota, the University of Nevada at Las Vegas, the US Geological Survey, the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Brigham Young University, the University of Nevada at Reno, the Wildlife Conservation Society, and Grand Canyon National Park.

Funding came from NASA; the National Park Service; the US Geological Survey; the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources; the Nevada Department of Wildlife; the Arizona Game and Fish Department; the US Department of Energy; Grand Canyon, Zion, and Capitol Reef national parks; the Bureau of Land Management; the US Forest Service; the US Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services; and the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Source: University of Michigan