Researchers have identified two compounds that are more potent and less toxic than current leukemia therapies.

Chemotherapy treatments generally have awful side effects, and it’s no secret that the drugs involved are often toxic to the patient as well as their cancer.

The idea is that, since cancers grow so quickly, chemotherapy will kill off the disease before its side effects kill the patient.

That’s why scientists and doctors are constantly searching for more effective therapies.

The newly identified molecules work in a different way than standard cancer treatments and could form the basis of an entirely new class of drugs. What’s more, the compounds are already used for treating other diseases, which drastically cuts the amount of red tape involved in tailoring them toward leukemia or even prescribing them off-label.

The findings appear in the Journal of Medical Chemistry.

“Our work on an enzyme that is mutated in leukemia patients has led to the discovery of an entirely new way of regulating this enzyme, as well as new molecules that are more effective and less toxic to human cells,” says Norbert Reich, professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Why chemotherapy is often so toxic

All cells in your body contain the same DNA, or genome, but each one uses a different part of this blueprint based on what type of cell it is. This enables different cells to carry out their specialized functions while still using the same instruction manual; essentially, they just use different parts of the manual. The epigenome tells cells how to use these instructions. For instance, chemical markers determine which parts get read, dictating a cell’s actual fate.

A cell’s epigenome is copied and preserved by an enzyme (a type of protein) called DNMT1. This enzyme ensures, for example, that a dividing liver cell turns into two liver cells and not a brain cell.

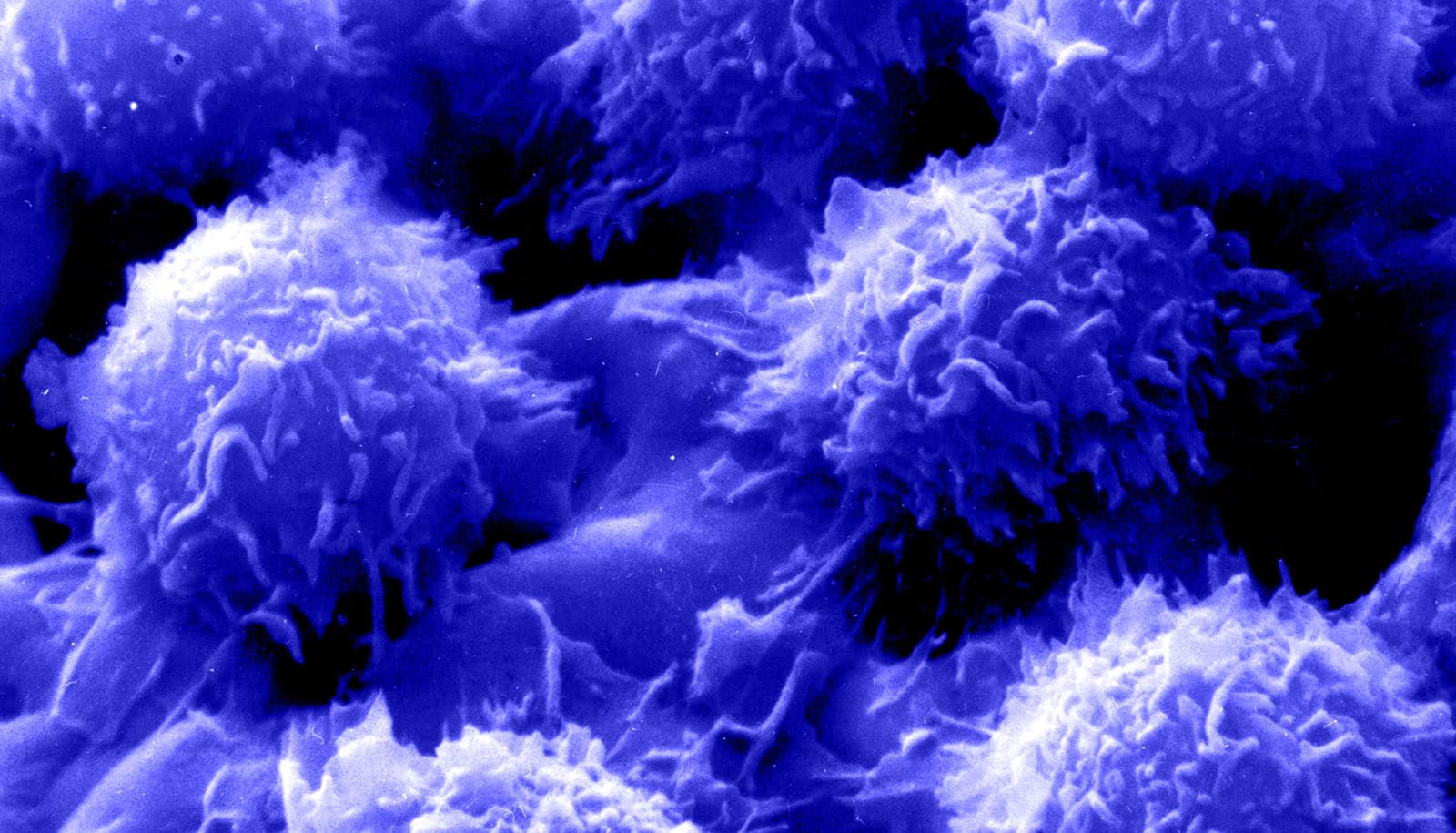

However, even in adults, some cells do need to differentiate into different kinds of cells than they were before. For example, bone marrow stem cells are capable of forming all the different blood cell types, which don’t reproduce on their own. This is controlled by another enzyme, DNMT3A.

This is all well and good until something goes wrong with DNMT3A, causing bone marrow to turn into abnormal blood cells. This is a primary event leading to various forms of leukemia, as well as other cancers.

Most cancer drugs are designed to selectively kill cancer cells while leaving healthy cells alone. But this is extremely challenging, which is why so many of them are extremely toxic. Current leukemia treatments, like Decitabine, bind to DNMT3A in a way that disables it, thereby slowing the progression of the disease. To do this, they clog up the enzyme’s active site (essentially, its business end) to prevent it from carrying out its function.

Unfortunately, DNMT3A’s active site is virtually identical to that of DNMT1, so the drug shuts down epigenetic regulation in all of the patient’s 30 to 40 trillion cells. This leads to one of the drug industry’s biggest bottle necks: off-target toxicity.

Clogging a protein’s active site is a straightforward way to take it offline. That’s why the active site is often the first place drug designers look when designing new drugs, Reich explains. However, about eight years ago he decided to investigate compounds that could bind to other sites in an effort to avoid off-target effects.

Leukemia mutations

As the group was investigating DNMT3A, they noticed something peculiar. While most of these epigenetic-related enzymes work on their own, DNMT3A always formed complexes, either with itself or with partner proteins. These complexes can involve more than 60 different partners, and interestingly, they act as homing devices to direct DNMT3A to control particular genes.

Former graduate student Celeste Holz-Schietinger led early work in the Reich lab that showed that disrupting the complex through mutations did not interfere with its ability to add chemical markers to the DNA. However, the DNMT3A behaved differently when it was on its own or in a simple pair; it wasn’t to stay on the DNA and mark one site after another, which is essential for its normal cellular function.

Around the same time, the New England Journal of Medicine ran a deep dive into the mutations present in leukemia patients. The authors of that study discovered that the most frequent mutations in acute myeloid leukemia patients are in the DNMT3A gene.

Surprisingly, Holz-Schietinger had studied the exact same mutations. The team now had a direct link between DNMT3A and the epigenetic changes leading to acute myeloid leukemia.

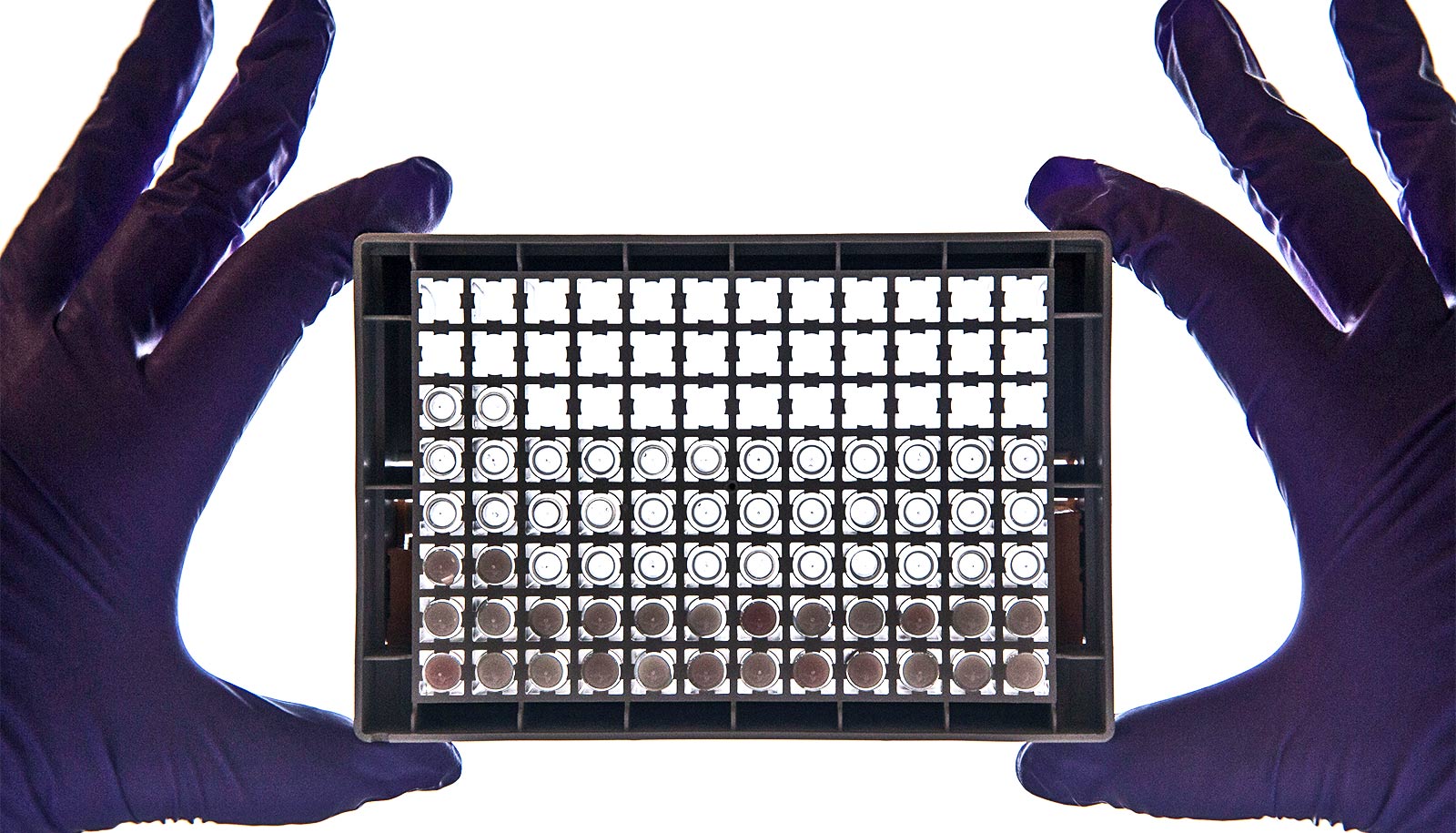

Reich and his group became interested in identifying drugs that could interfere with the formation of DNMT3A complexes that occur in cancer cells. They obtained a chemical library containing 1,500 previously studied drugs and identified two that disrupt DNMT3A interactions with partner proteins (protein-protein inhibitors, or PPIs).

What’s more, these two drugs do not bind to the protein’s active site, so they don’t affect the DNMT1 at work in all of the body’s other cells. “This selectivity is exactly what I was hoping to discover with the students on this project,” Reich says.

These drugs are more than merely a potential breakthrough in leukemia treatment. They are a completely new class of drugs: protein-protein inhibitors that target a part of the enzyme away from its active site.

“An allosteric PPI has never been done before, at least not for an epigenetic drug target,” Reich says. “It really put a smile on my face when we got the result.”

This achievement is no mean feat. “Developing small molecules that disrupt protein-protein interactions has proven challenging,” notes lead author Jonathan Sandoval of the University of California, San Francisco, a former doctoral student in Reich’s lab. “These are the first reported inhibitors of DNMT3A that disrupt protein-protein interactions.”

The two compounds the team identified have already been used clinically for other diseases. This eliminates a lot of cost, testing, and bureaucracy involved in developing them into leukemia therapies. In fact, oncologists could prescribe these drugs to patients off label right now.

What about long-term effects?

There’s still more to understand about this new approach, though. The team wants to learn more about how protein-protein inhibitors affect DNMT3A complexes in healthy bone marrow cells. Reich is collaborating with Tom Pettus, a chemistry professor at UC Santa Barbara and Ivan Hernandez , a joint doctoral student of theirs. “We are making changes in the drugs to see if we can improve the selectivity and potency even more,” Reich says.

There’s also more to learn about the drugs’ long-term effects. Because the compounds work directly on the enzymes, they might not change the underlying mutations causing the cancer. This caveat affects how doctors can use these drugs.

“One approach is that a patient would continue to receive low doses,” Reich says. “Alternatively, our approach could be used with other treatments, perhaps to bring the tumor burden down to a point where stopping treatment is an option.”

Reich also admits the team has yet to learn what effect the PPIs have on bone marrow differentiation in the long term. They’re curious if the drugs can elicit some type of cellular memory that could mitigate problems at the epigenetic or genetic level.

That said, Reich is buoyed by the discovery. “By not targeting DNMT3A’s active site, we are already leagues beyond the currently used drug, Decitabine, which is definitely cytotoxic,” he says, adding that this type of approach could be tailored to other cancers as well.

Additional coauthors are from UC San Francisco, Baylor College of Medicine, and UC Santa Barbara.

Source: UC Santa Barbara