X-ray microscopy reveals lead compounds in red and black inks on 12 ancient Egyptian papyrus fragments.

The researchers suggest they were used for their drying properties rather than as a pigment. A similar lead-based “drying technique” has also been documented in 15th century European painting, and the discovery of it in Egyptian papyri calls for a reassessment of ancient lead-based pigments.

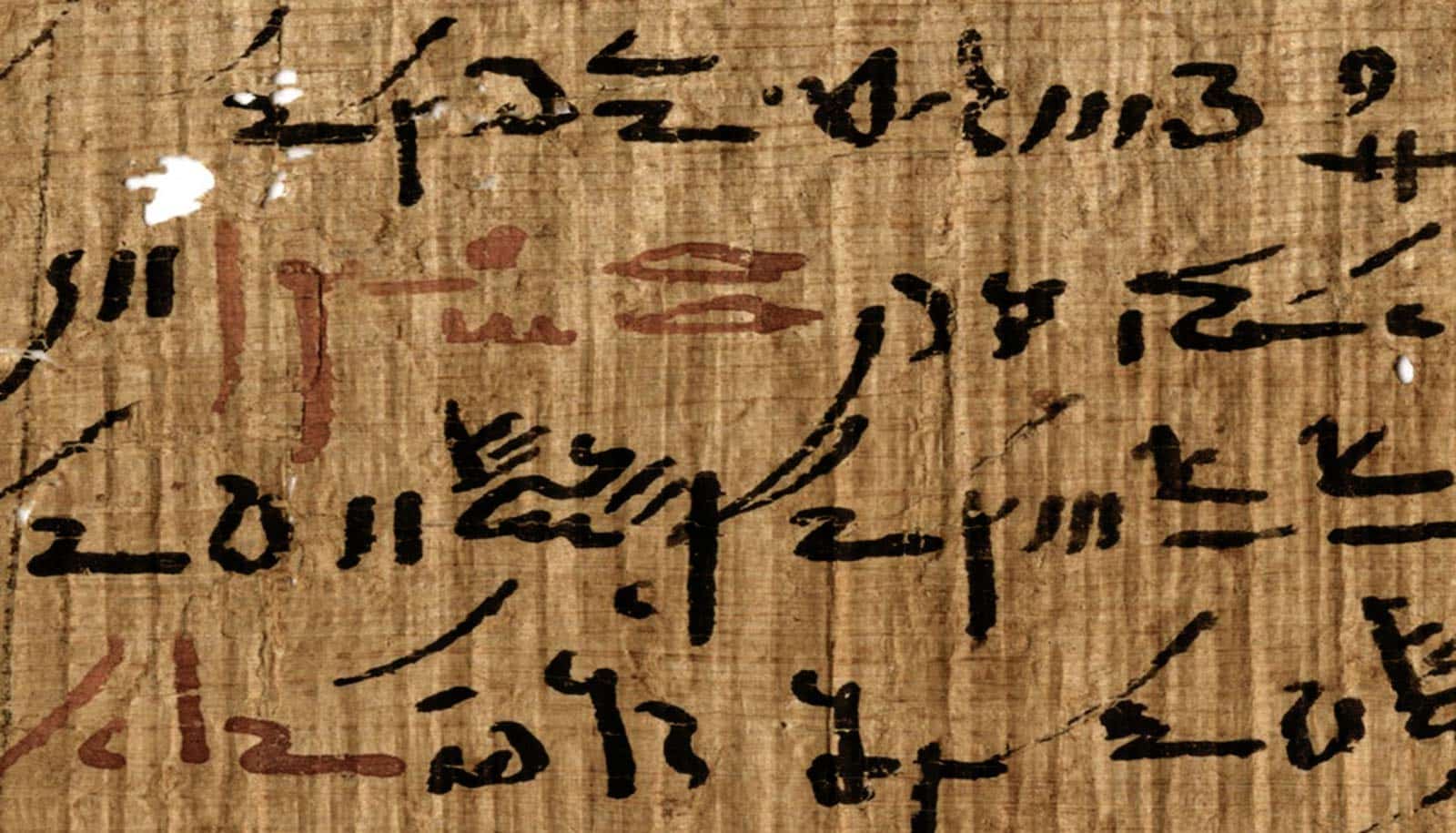

The ancient Egyptians have been using inks for writing since at least 3200 BCE, using black inks for the primary body of text and using red inks to highlight headings and keywords. As reported in PNAS, researchers used advanced synchrotron radiation based X-ray microscopy equipment to investigate red and black inks preserved on the papyrus fragments from Roman period Egypt (around 100 to 200 CE).

“Our analyses of the inks on the papyri fragments from the unique Tebtunis temple library revealed previously unknown compositions of red and black inks, particularly iron-based and lead-based compounds,” says Egyptologist and first author of the study Thomas Christiansen from the University of Copenhagen.

“The iron-based compounds in the red inks are most likely ocher—a natural earth pigment—because the iron was found together with aluminum and the mineral hematite, which occur in ocher,” adds chemistry professor and coauthor Sine Larsen. “The lead compounds appear in both the red and black inks, but since we did not identify any of the typical lead-based pigments used to color the ink, we suggest that this particular lead compound was used by the scribes to dry the ink rather than as a pigment.”

A similar lead-based drying technique was used in 15th century Europe during the development of oil painting, and the researchers believe that the Egyptians must have discovered 1,400 years earlier that they could ensure their papyri did not smear by applying this particular ink. According to the researchers, their discovery calls for a reassessment of lead-based compounds found in ancient Mediterranean inks in that drying techniques may have been widespread much earlier than previously believed.

The studied papyri fragments all form part of larger manuscripts belonging to the Papyrus Carlsberg Collection at the University of Copenhagen, more specifically from the Tebtunis temple library, which is the only surviving large-scale institutional library from ancient Egypt. The temple priests, who wrote the analyzed papyri manuscripts, did probably not manufacture the inks themselves as the complexity of particularly the red inks must have required specialist knowledge:

“Judging from the amount of raw materials needed to supply a temple library as the one in Tebtunis, we propose that the priests must have acquired them or overseen their production at specialized workshops much like the Master Painters from the Renaissance,” Christiansen explains.

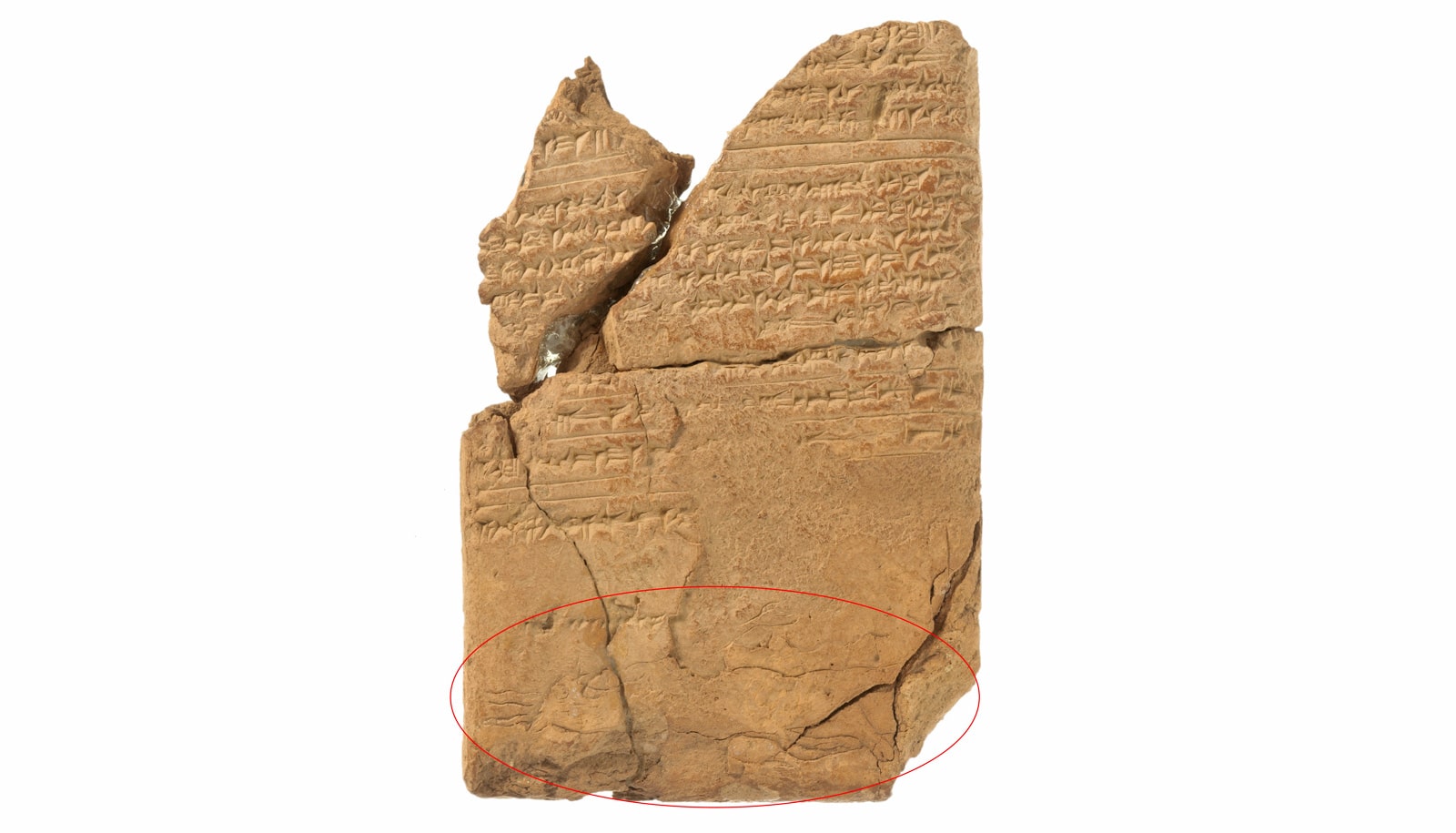

“The advanced synchrotron-based microanalyses have provided us with invaluable knowledge of the preparation and composition of red and black inks in ancient Egypt and Rome 2,000 years ago. And our results are supported by contemporary evidence of ink production facilities in ancient Egypt from a magical spell inscribed on a Greek alchemical papyrus, which dates to the third century [CE]. It refers to a red ink that was prepared inside a workshop.

“This papyrus was found in Thebes, and it may well have belonged to a priestly library like the papyri studied here, thus providing insights into some of the chemical arts applied by Egyptian priests of the late Roman period.”

The investigation took place at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble as part of the CoNext project on equipment that has made it possible to probe the chemical composition from the millimeter to the submicrometer scale. The work provides information not only on the elemental, but also the molecular and structural composition of the inks.

According to the researchers, their results will also be useful for conservation purposes as detailed knowledge of the material’s composition could help museums and collections preserve cultural heritage objects.

Source: University of Copenhagen