Mental health therapy from trained community-based lay counselors improves trauma-related symptoms up to a year later, a clinical trial with more than 600 children in Kenya and Tanzania shows.

Researchers trained laypeople as counselors to deliver treatment in both urban and rural communities in Kenya and Tanzania, and evaluated the progress of children and their guardians through sessions of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy.

The findings demonstrate that lower-cost, scalable mental health solutions are possible for a part of the world where mental health resources are scarce, researchers say.

An estimated 140 million children around the world have experienced the death of a parent, which can result in grief, depression, anxiety, and other physical and mental health conditions.

In low- and middle-income countries, many of those children end up living with relatives or other caregivers where mental health services are typically unavailable.

“Very few people with mental health needs receive treatment in most places in the world, including many communities in the US,” says Shannon Dorsey, a professor of psychology at the University of Washington and lead author of the paper in JAMA Psychiatry. “Training community members, or ‘lay counselors’ to deliver treatment helps increase the availability of services.”

Talk it out

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a type of talk therapy, generally involves focusing on thoughts and behavior, and how changing either or both can lead to feeling better. When counselors use CBT for traumatic events, it involves talking about the events and related difficult situations instead of trying to avoid thinking about or remembering them.

Researchers have tested the approach before among children, and in areas with little access to mental health services, Dorsey says. However, the new study is the first clinical trial outside high-income countries to examine improvement in post-traumatic stress symptoms in children over time.

The research builds on work from coauthor Kathryn Whetten, a professor of public policy and global health at Duke University. Whetten has conducted longitudinal research in Tanzania and four other countries on the health outcomes of some 3,000 children who have lost one or both parents.

“They could see, as one child said, ‘I’m not the only one who worries about who will love me now that my mama is gone.'”

“While concerned with the material needs of the household, caregivers of the children repeatedly asked the study team to find ways to help with the children’s behavioral and emotional ‘problems’ that made it so that that the children did not do well in school, at home, or with other children,” Whetten says.

“We knew these behaviors were expressions of anxiety that likely stemmed from their experiences of trauma. We therefore sought to adapt and test an intervention that could help these children succeed.”

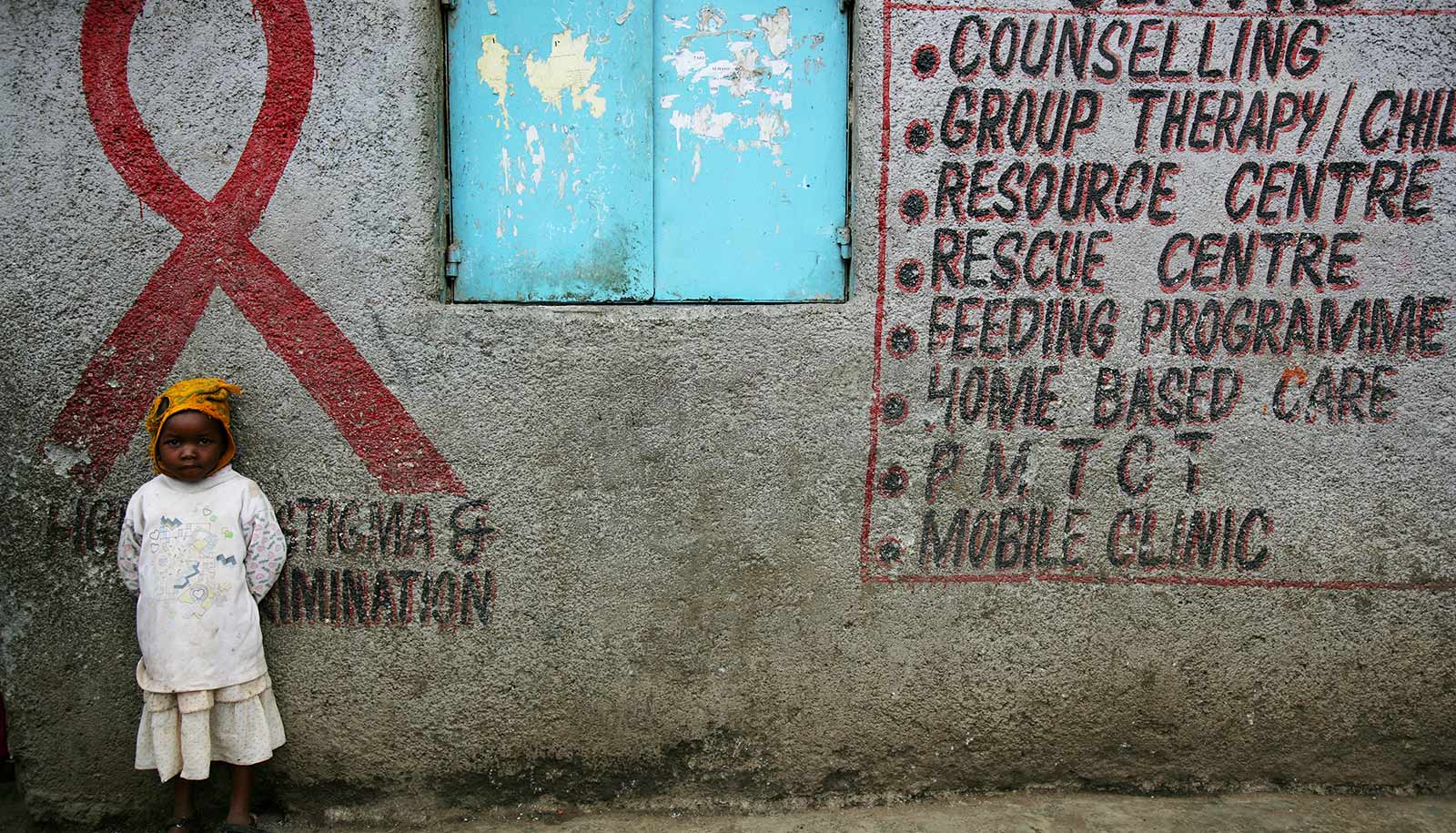

Africa is home to about 50 million orphaned children, mostly due to HIV/AIDS and other health conditions.

Therapy normalizes experiences

For the Kenya-Tanzania study, two local nongovernmental organizations, Ace Africa and Tanzania Women Research Foundation, recruited counselors and trained them in CBT methods.

Based on researchers’ prior experience in Africa, the team adapted the CBT model and terminology, structuring it for groups of children in addition to one-on-one sessions. They referred to the sessions as a “class” offered in a familiar building such as a school, rather than as “therapy” in a clinic. The changes aimed to reduce stigma and boost participation in and comfort with the program, Dorsey says.

“Having children meet in groups naturally normalized their experiences. They could see, as one child said, ‘I’m not the only one who worries about who will love me now that my mama is gone.’ They also got to support each other in practicing skills to cope with feelings and to think in different ways in order to feel better,” she says.

“The children learned…you have to convert that relationship to one of memory, but it is still a relationship that can bring comfort.”

Counselors provided 12 group sessions over 12 weeks, along with 3 to 4 individual sessions per child. Caregivers participated in their own group sessions, a few individual sessions and group activities with the children. Activities and discussions centered on helping participants process the death of a loved one: being able to think back on and talk about the circumstances surrounding the parent’s death, for example, and learning how to rely on memories as a source of comfort.

In one activity, children drew a picture of something their parent did with them, such as cooking a favorite meal or walking them to school. Even though children could no longer interact with the parent, the counselors explained that children could hold onto these memories and what they learned from their parents, like how to cook the meal their mother made, or the songs their father taught them.

“The children learned that you don’t lose the relationship,” Dorsey says. “You have to convert that relationship to one of memory, but it is still a relationship that can bring comfort.”

The guardians learned similar coping skills, she says. Relatives usually care for children who have experienced parental death, so they often are also grieving the loss of a family member while taking on the challenge of an additional child in the home.

Potential of lay counselors

Researchers interviewed participants at the conclusion of the 12-week program, and again six and 12 months later. Researchers evaluated a control group of children, who received typical community services offered to orphaned children, such as free uniforms and other, mostly school fee-related help, concurrently.

Improvement in children’s post-traumatic stress symptoms and grief was most pronounced in both urban and rural Kenya. Researchers attribute the success there partly to the greater adversity children faced, such as higher food scarcity and poorer child and caregiver health, and thus the noticeable gains that providing services could yield.

In contrast, in rural Tanzania, children in both the counseling and control groups showed similar levels of improvement, which researchers are now trying to understand. One possible explanation Dorsey says, is that children and caregivers in Tanzania, and particularly in rural areas, may have been more likely to share with others in their village what they learned from therapy.

Even with the different outcomes in the two countries, the intervention by lay counselors who received training from experienced lay counselors shows the effectiveness and scalability of fostering a local solution, Dorsey says. Members of the research team are already working in other countries in Africa and Asia to help lay counselors train others in their communities to work with children and adults.

“If we grow the potential for lay counselors to train and supervise new counselors and provide implementation support to systems and organizations in which these counselors are embedded, communities can have their own mental health expertise,” Dorsey says.

“That would have many benefits, from lowering cost to improving the cultural and contextual fit of treatments.”

The National Institute of Mental Health funded the work. Additional coauthors are from Duke, the University of Washington, Johns Hopkins University, Ace Africa, the Tanzania Women Research Foundation, Drexel University College of Medicine, and Kilimanjaro Christian University Medical College.

Source: Duke University