An enormous volcanic eruption on Iceland in 1783-84 didn’t cause an extreme summer heat wave in Europe, but it did trigger an unusually cold winter, according to a new study.

Researchers say the findings, which appear in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, will help improve predictions of how the climate will respond to future high-latitude volcanic eruptions.

The eight-month eruption of the Laki volcano, beginning in June 1783, was the largest high-latitude eruption in the last 1,000 years. It injected about six times as much sulfur dioxide into the upper atmosphere as the 1883 Krakatau or 1991 Pinatubo eruptions, says coauthor Alan Robock, professor in the environmental sciences department at Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

The eruption coincided with unusual weather across Europe. The summer was unusually warm with July temperatures more than 5 degrees Fahrenheit above the norm, leading to societal disruption and failed harvests. The 1783–84 European winter was up to 5 degrees colder than average.

(Credit: Alan Robock/Rutgers)

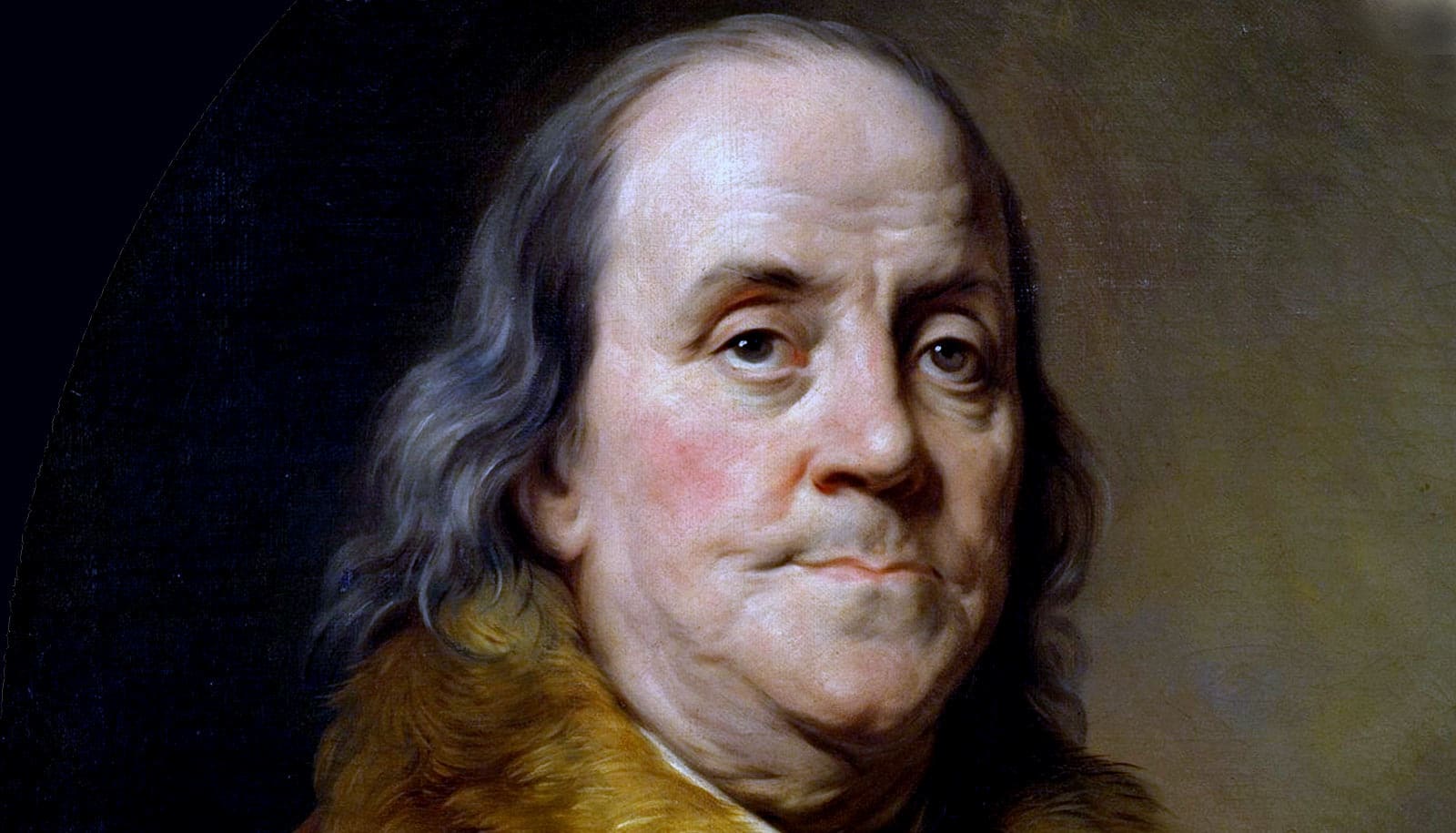

Benjamin Franklin, the US ambassador to France, speculated on the causes in a 1784 paper, the first publication in English on the potential impacts of a volcanic eruption on the climate.

“…even with a large eruption like Laki, it will be impossible to predict very local climate impacts because of the chaotic nature of the atmosphere.”

To determine whether Franklin and other researchers were right, researchers performed 80 simulations with a state-of-the-art climate model from the National Center for Atmospheric Research. The computer model included weather during the eruption and compared the ensuing climate with and without the effects of the eruption.

“It turned out, to our surprise, that the warm summer was not caused by the eruption,” Robock says. “Instead, it was just natural variability in the climate system. It would have been even warmer without the eruption. The cold winter would be expected after such an eruption.”

More than 60 percent of Iceland’s livestock died within a year, and about 20 percent of the people died in a famine. Reports of increased death rates and/or respiratory disorders crisscrossed Europe.

“Understanding the causes of these climate anomalies is important not only for historical purposes, but also for understanding and predicting possible climate responses to future high-latitude volcanic eruptions,” Robock says.

“Our work tells us that even with a large eruption like Laki, it will be impossible to predict very local climate impacts because of the chaotic nature of the atmosphere.”

Scientists continue to work on the potential impacts of volcanic eruptions on people through the Volcanic Impacts on Climate and Society project and will include the Laki eruption in their research. Volcanic eruptions can have global climate impacts lasting several years.

Brian Zambri, a former postdoctoral associate who earned his doctorate at Rutgers, now at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is the study’s lead author. Scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and University of Cambridge contributed to the study.

Source: Rutgers University