Researchers have discovered the longest-ever glacier record for the tropics, and among the longest records of historical climate.

When Mark Abbott and his team pulled a 300-foot-long core of mud from a lakebed high in the Peruvian Andes, he hoped it might provide a long-sought-after glimpse of the past 160,000 years of climate change.

“This is unlike anything we had before.”

Instead, that lakebed recorded the ebb and flow of glaciers for more than 700,000 years, the researchers report.

In the lake mud, the researchers found clues for how climate change may shape the modern-day world.

Like pages of a history book

“This is unlike anything we had before,” says Abbott, a geology and environmental science professor at the University of Pittsburgh. “We now have a land-based record of glaciation from the tropics that is in many ways equal to our records from the ice caps at the poles and from the ocean, and that’s really been lacking.”

Researchers have known for decades that Lake Junin is a rare gem. Situated more than 13,000 feet above sea level in the Andes, the lake meets all the right conditions to archive the shifting glacial epochs: It’s close enough to glaciers that it catches sediment and water that flows down the mountains, but distant enough to have not been overrun by glaciers itself since it formed.

Having avoided disruption by millennia of churning ice, the lake’s sediments remain stacked in order by the year they were laid down like the pages of a history book.

Actually accessing that recorded history, however, took researchers more than 20 years.

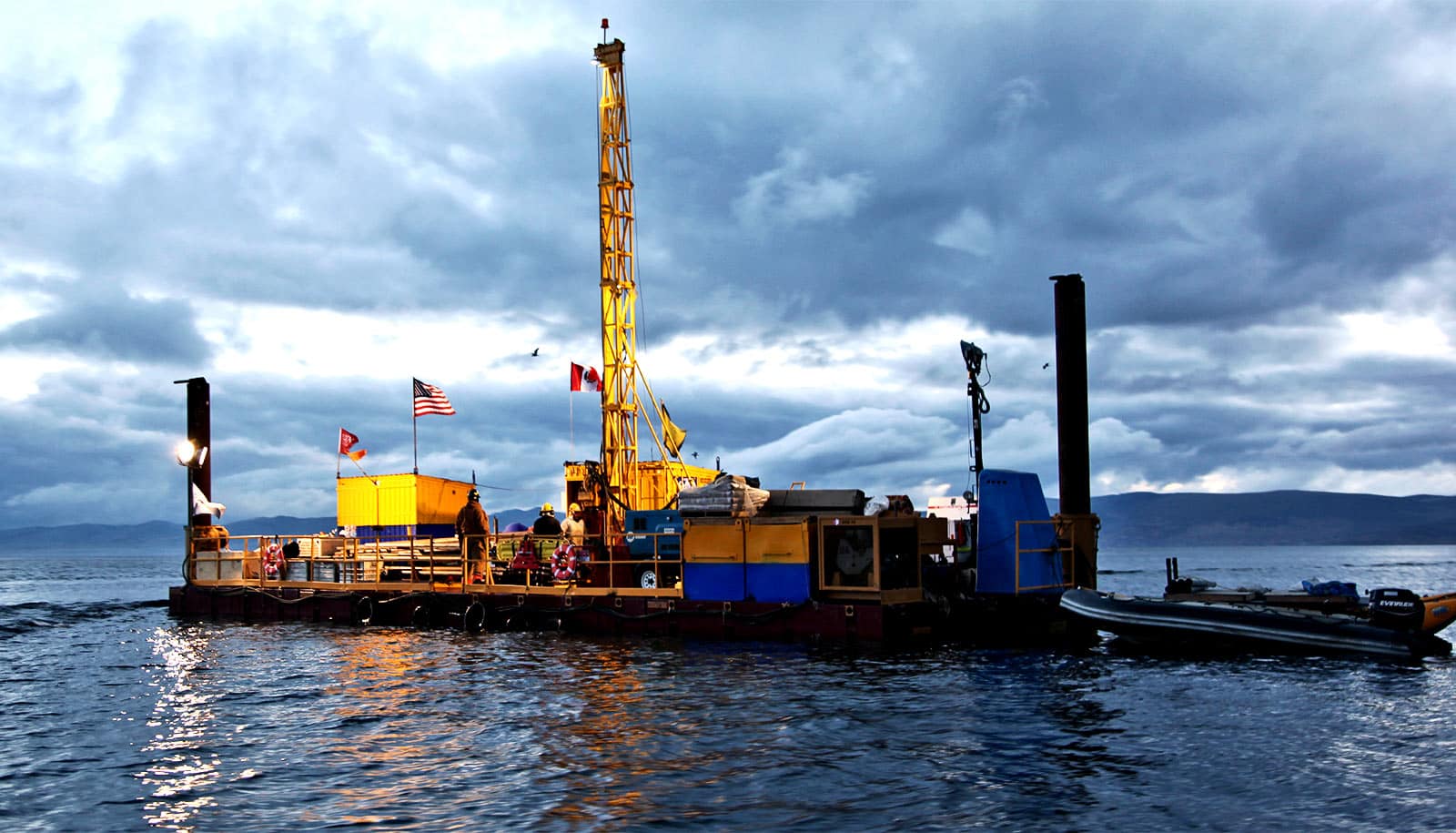

“It’s remote, high, and hard to get to,” says Abbott, who also serves as director for the Climate and Global Change Center at the University of Pittsburgh. “There are no boats on the lake, and it’s ringed by marshes—it’s a very difficult site to work on with heavy equipment, so it was a huge effort to pull this together.”

With a long, detailed record of climate change in the tropics, the team was able to compare the history of global climate change in a way that previously wasn’t possible.

The glacier history contained in the lake core matched up with those found elsewhere, showing a roughly 100,000-year cycle in amounts of ice across the globe. But it also revealed some curiosities.

“What we’ve tried to do here is tie this to records in the poles and the oceans and see how they’re different over time,” Abbott says. For instance, “there was a period between about 400,000 to 200,000 years ago where it looks like the tropics are wetter than the poles.”

Climate change ahead

Reading the record meant dividing the 300-foot-long core into thousands of pieces and carefully shaving off and studying the layers of sediment. A layer’s makeup reveals how it was formed—whether glaciers grinding against rocks or the lake drying up to form a wetland, each process leaves its own distinct trace.

Analyzing the sediment’s geochemical and magnetic properties allowed researchers to figure out how temperature and precipitation changed over time. The team also used multiple methods, including radiocarbon dating performed by geology and environmental science PhD student Arielle Woods, to determine when each layer was deposited.

Comparing the 700,000 years of climate change from Lake Junin with those found elsewhere in the world revealed patterns that may serve as clues for what to expect as the world heats up in the 21st century.

“When the Arctic warmed, the southern tropics dried out dramatically. You shift heat into the southern hemisphere, and the monsoon weakens, effectively, so you get very dry conditions,” Abbott says.

That’s especially noteworthy because of how many people rely on the predictability of monsoons for growing crops. And it’s one more piece of evidence for an idea that’s familiar to anyone who studies the planet’s climate.

“The global climate is very connected,” he says. “If you change something anywhere on the globe, you see its effects virtually everywhere.”

The research appears in the journal Nature.

Additional researchers from the University of Pittsburgh, Union College, the University of Florida, and a number of other academic institutions contributed to the work.

Source: Patrick Monahan for University of Pittsburgh