Using data from a 2008 outbreak of one of the most feared “superbugs” and modern genetic sequencing techniques, a team successfully modeled and predicted the way the organism spread among dozens of health care facilities.

The approach can tell if the bug is spreading within a hospital, nursing home, or long-term acute care hospital, or if a new patient transferred from another facility brought it there.

The approach, published in Science Translational Medicine, combines current epidemiological approaches with whole-genome sequencing, spelling out the entire DNA sequence of bacteria from each infected patient.

In other words, if fighting superbugs is like a horror movie, the approach can tell if the call is coming from inside the house, or if the killer is lurking outside and about to barge through the door.

And just like in a horror movie, getting an answer quickly can guide what kinds of barricades and weapons health professionals should use against the villain.

This makes it possible to use the tiny changes in superbug DNA—the kind of mutations that happen naturally over time—to track their spread within and between health care facilities.

A team from Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and the University of Michigan Medical School developed the technique using data on a 2008 outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumonia (CRKP) in the upper Midwest.

“These organisms permeate regions, but it hasn’t been understood in detail how that happens—why they spread like wildfire in one region and don’t make headway in another,” says Evan Snitkin, assistant professor specializing in bioinformatics and systems biology at the University of Michigan.

“Because this was the first outbreak of CRKP in the Chicago region, we decided to try to trace its initial movements based on patient transfers and whole-genome sequencing of samples. If we can understand what drives transmission in a region, we hope to be able to intervene to prevent further spread.”

Transmission hub

Rush’s hospital identified the second case of CRKP in the region. The hospital team identified the outbreak after a patient arrived at their emergency department in a transfer from an acute care hospital in Indiana.

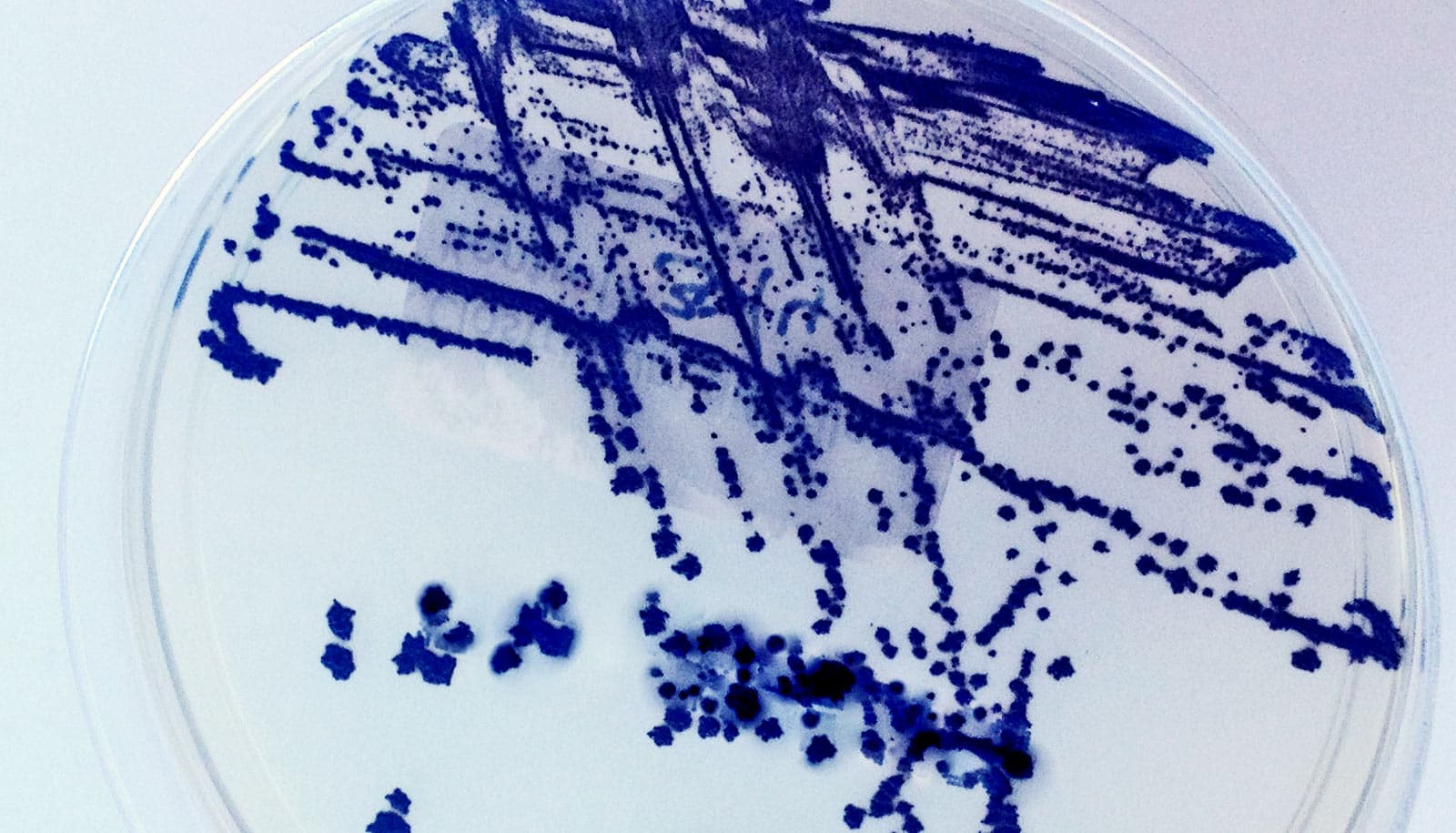

A team led by Mary K. Hayden, an infectious diseases physician who directs Rush’s division of clinical microbiology, conducted and published its own investigation of the outbreak, using the best techniques available at the time. The team concluded that the bug spread from a single patient in mid-2007, eventually infecting 42 people treated in 14 acute care hospitals, two LTACHs, and 10 nursing homes.

Transfers of patients among these facilities—for example, from an LTACH or nursing home to a hospital for short-term acute care, and then back again—emerged as a major driver of spread. A single LTACH was fingered as a key hub for transmission.

In this outbreak, many patients died. Nationwide, death rates for CRKP are even higher, and it tends to prey upon the sickest, most vulnerable patients.

‘The future arrived’

Back in 2008, whole-genome sequencing of this many samples was not feasible.

“The earlier we can intervene to contain an outbreak, the more likely it is that we can eradicate it.”

“Although our research fellow at the time, Dr. Sarah Won, conducted an exhaustive outbreak investigation, the molecular epidemiologic tools available in 2008 did not allow us to determine timing and direction of spread for many cases,” says Hayden. “We saved the isolates with the hope that more discriminating techniques would be available in the future. We were very excited when the future arrived!”

The Rush team brought the samples to the University of Michigan’s Center for Microbial Systems for sequencing, and Snitkin’s team started to put the genome data together with what Hayden’s team had found out about the outbreak. This included something that hadn’t been available before the original outbreak report: clinical data on “patient zero,” the person whom Hayden’s team had previously identified as the origin of the outbreak.

This allowed the team to create a “family tree” of the CRKP outbreak, back to that first patient on the trunk. They mapped the spread from patient to patient, and facility to facility, based on both the sleuthwork from Hayden’s team and the new genomic sequence information.

They could see which cases had resulted from transmission within the facility—because of practices that allowed bacteria from the infected patient to reach others—and which had been introduced because a patient was transferred with the bacteria already inside them.

Sidekick for antibiotics would ‘gunk up’ superbugs

Then, they tested the approach by trying to predict which facility each patient’s CRKP infection had come from, using only the genomes of the other patients already treated in the outbreak and none of the information from patients treated later.

This real-time analysis, similar to what might happen in a real outbreak, successfully pinpointed the facility where the infection came from for every patient.

Faster intervention

“The genome sequence is powerful for finding pathways, but having epidemiological data about exposures and movement between facilities makes everything make sense,” says Snitkin, who holds positions in the University of Michigan Medical School’s departments of microbiology & immunology and internal medicine. “We envision that we will be able to use this same approach on other organisms, too, though efficacy will vary.”

Adds Hayden, “This approach might be particularly useful in identifying pathways of transmission soon after emergence of a superbug in a region. The earlier we can intervene to contain an outbreak, the more likely it is that we can eradicate it.”

Antibiotics can goad ‘superbugs’ into ganging up on us

Going forward, the team hopes to test the approach in other settings, to see if it can find the hubs of antibiotic-resistant bacteria development and transmission.

The team also will test the approach for its ability to trace the origin of transmission for an organism that’s already present in an area. This could be much harder than tracking a newly introduced type of infection that has just entered a region.

The role of LTACHs, where patients may live for months at a time receiving hospital-level care such as constant ventilation, is one the researchers also hope to explore further. Such facilities may be especially prone to the development of antibiotic-resistant organisms simply because of the kind of care they provide to a very vulnerable and immobile population with weak immune systems.

In the long run, the researchers hope their approach could be adapted broadly by public health authorities and infection control specialists in health care facilities—and used to steer interventions very early in an outbreak to prevent transmission across broad networks.

To get to that point will require the development of public-domain software for public health disease detectives to use routinely, or even to automate the process.

The CDC as well as the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation funded the work. Additional researchers contributed from the University of Michigan, and Cook County Health and Hospitals System.

Source: University of Michigan