Kirigami-inspired techniques have allowed researchers to design thin sheets of material that automatically reconfigure into new two-dimensional shapes and three-dimensional structures in response to environmental stimuli.

The researchers created a variety of robotic devices as a proof of concept for the approach.

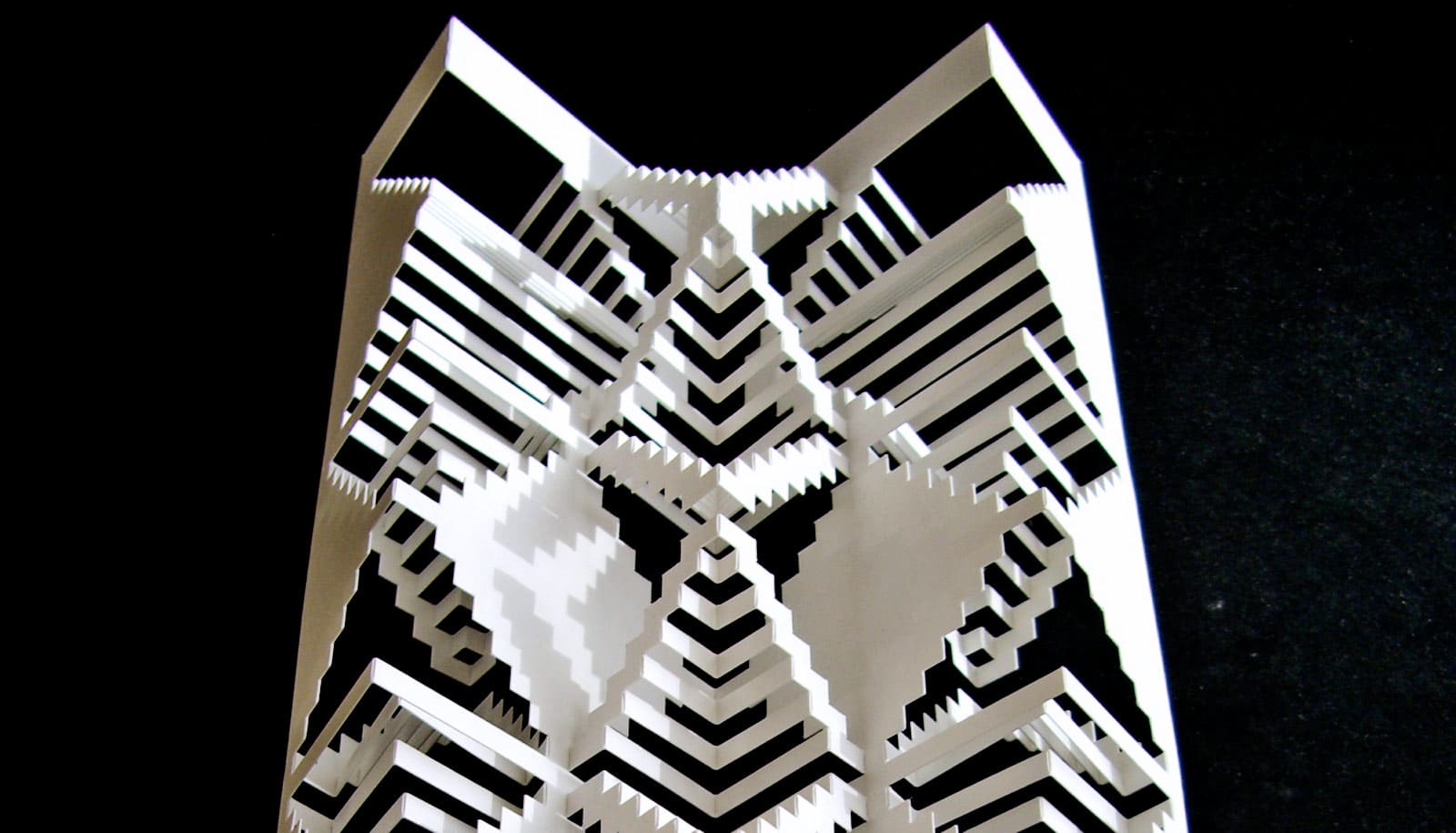

Kirigami is an art form in which a single piece of paper is cut and folded to create new shapes and structures.

“This is the first case that we know of in which 2D kirigami patterns autonomously reshape themselves into distinct 3D structures without mechanical input,” says corresponding author Jie Yin, an assistant professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at North Carolina State University and corresponding author of a paper on the work. “Instead, we apply energy in the form of heat, and the material rearranges itself.”

The new “active kirigami” concept relies on a three-layered material, consisting of two outer layers that are not responsive to heat, and a polymer layer in the middle that contracts in response to heat.

The shape and structure of the material are controlled in two ways. Through-cuts, which penetrate all three layers, control the material’s range of motion. Etchings, which penetrate the outer layers and expose the heat-responsive polymer, control the angle and direction at which the material folds, as well as how far it folds. As the material folds, it opens the through-cuts, shifting the shape of the sheets into 2D or 3D designs.

“We can make a 2D template with the same pattern of through-cuts and use it to create many different 3D structures by making slight changes in the etching,” Yin says. “This effectively makes the active kirigami sheets programmable.”

As part of their proof of concept, researchers used their kirigami approach to create a suite of thermoresponsive kirigami machines, including simple gripping devices and self-folding boxes. The researchers also created a soft robot with a kirigami body and pneumatic legs. By switching the orientation of the body, the researchers could rapidly reposition the legs, changing the robot’s direction of movement.

“We used a temperature-responsive polymer for this work, but there’s no reason to think that other stimuli-responsive polymer materials—like photoactive liquid crystals—wouldn’t work as well,” Yin says. “We’re excited to explore the potential range of applications for these programmable, active kirigami materials.”

The paper appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Yanbin Li, a PhD student at NC State, is a first author of the study. Additional researchers are from Temple University, Penn, and NC State. The National Science Foundation funded the work.

Source: NC State