After big winter storms, clumps of kelp forests often wash ashore along the Southern California coast. But, contrary to the devastation these massive piles of seaweed might indicate, the kelp may rebound pretty quickly, thanks to neighboring beds.

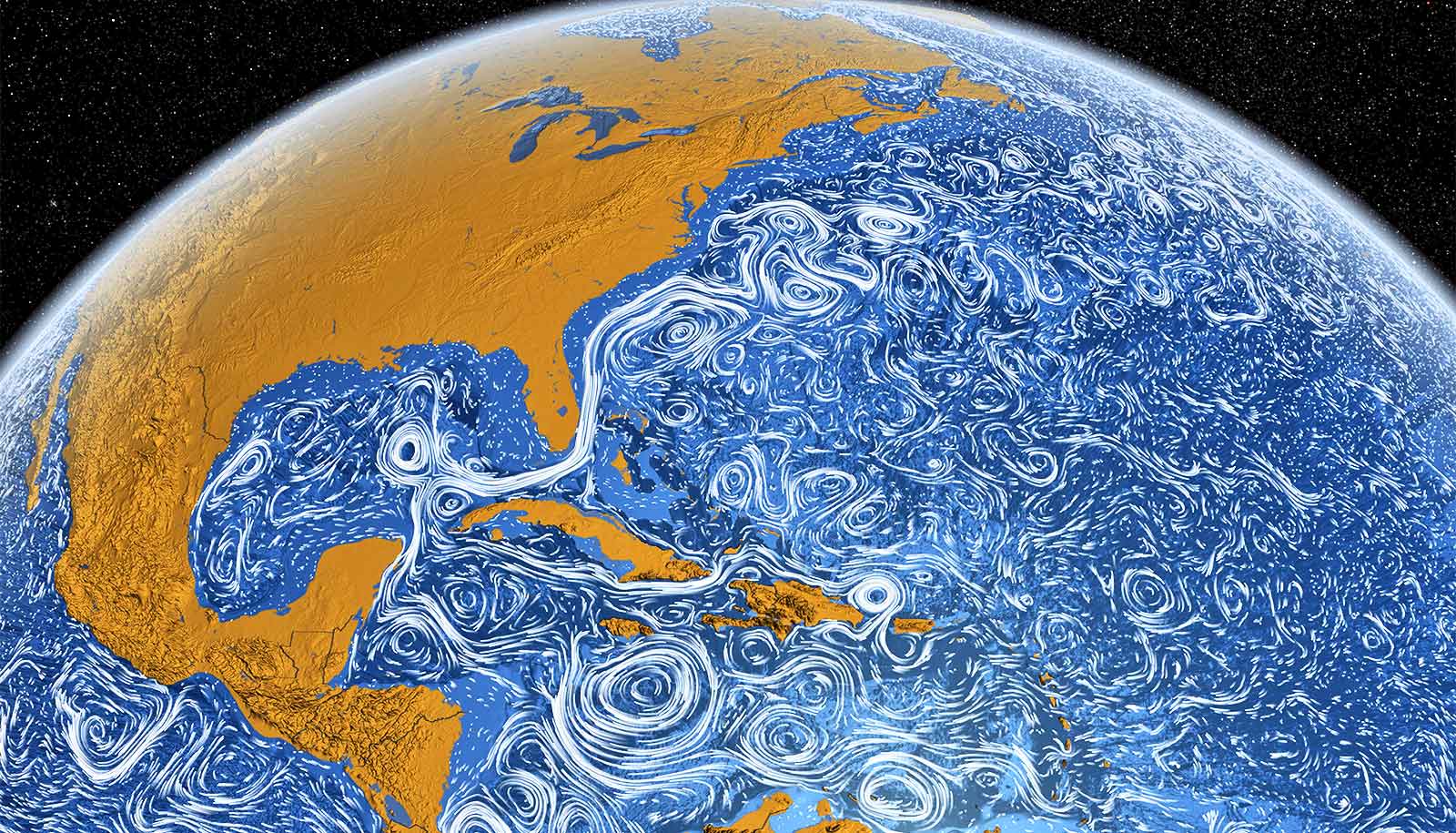

A new study shows that in much the same way that the wind scatters plant seeds over the land, ocean currents carry trillions of microscopic spores from one kelp forest to another, where they create life for ailing populations. The findings appear in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

“Historically, researchers thought that kelp forest resilience depended on only the local environment,” says lead author Max Castorani, a postdoctoral scholar at the Marine Science Institute at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “However, that turned out to be wrong, as we showed that kelp forests from miles away influence whether a local kelp forest persists or goes extinct. Declining kelp forests can be rescued or recolonized by neighboring populations, so the proximity among forests is very important.”

For example, kelp forests off the coast of Santa Barbara are linked to neighboring beds near Montecito and Goleta Beach but also to those farther away—as far south as Carpinteria and as far north as Isla Vista and the Gaviota coast.

Warm spell didn’t phase these giant kelp forests

“From year to year, the ocean currents change and the size of kelp populations expand or contract,” Castorani says. “In a given year, we could estimate how many spores were sent among all the hundreds of kelp forests in Southern California, allowing us to identify important rescuing populations.”

To measure kelp abundance from San Diego to Point Conception, researchers used data from a 32-year time series assembled from Landsat satellite images. This was calibrated to kelp abundance and spore production gathered from diving expeditions.

Also included was more than a decade of Southern California oceanographic modeling performed by coauthors David Siegel and Rachel Simons of UCSB’s Earth Research Institute.

The analysis overall showed that the chance of a population being rescued depends on the size of the neighboring forest, the number of spores it produces, and the strength of ocean currents that carry the spores.

“Of these factors, year-to-year changes in spore production turned out to be the most important to successfully rescuing neighboring kelp populations,” Castorani says. “This is valuable to ocean conservation because it can inform which kelp forests should be prioritized for protection or where coastal restoration efforts could be most effective.”

Researchers from the University of California, Santa Cruz, and the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, are coauthors of the work, which was funded by the National Science Foundation.

Source: UC Santa Barbara