Biodiversity gives kelp forests more stability than scientists previously believed, according to a new study.

An ecosystem arises from the effects of many different levels of organization. There are the species, their populations, the communities they live in, and the network of these communities over the entire region. But scientists are still exploring how the dynamics at different levels combine to determine the properties of the ecosystem as a whole.

“We wanted to understand which factors were most important in stabilizing the regional biomass of the macroalgae that thrive beneath the canopy of giant kelp,” says lead author Thomas Lamy, a postdoctoral scholar at the Marine Science Institute at the University of California, Santa Barbara. A stable community might see changes in its composition over time, but the overall mass of the plants and animals will remain relatively constant.

“Natural ecosystems are like Russian dolls…”

Scientists associate stability with two general characteristics: the diversity of different species and the number of patches in the region. If a region has many species, at least some will do well under a given set of conditions. Having a large number of independent communities can also promote stability. In this case, the health of each patch rises and falls independently, so they tend to average out, increasing the overall stability of the ecosystem.

Comparing an ecosystem to an investment portfolio, the stability biodiversity provides would be like having a very diverse portfolio of companies. The spatial stability would be like investing over a large geographic region. Both aspects stabilize the system in different ways and to different extents.

Lamy and his colleagues were surprised to find a great deal of synchrony between the health of different patches of reef.

“I didn’t expect the spatial effects to be almost completely swamped out by the species effects,” says coauthor Bob Miller, a research biologist with the Marine Science Institute. “Essentially, you’re getting more stability from having more species than you are from having more patches of reef where those species live.”

One possible explanation for this uniformity is that water tends to even out temperature differences, making variation negligible across a large area, in contrast with more variable conditions across terrestrial landscapes.

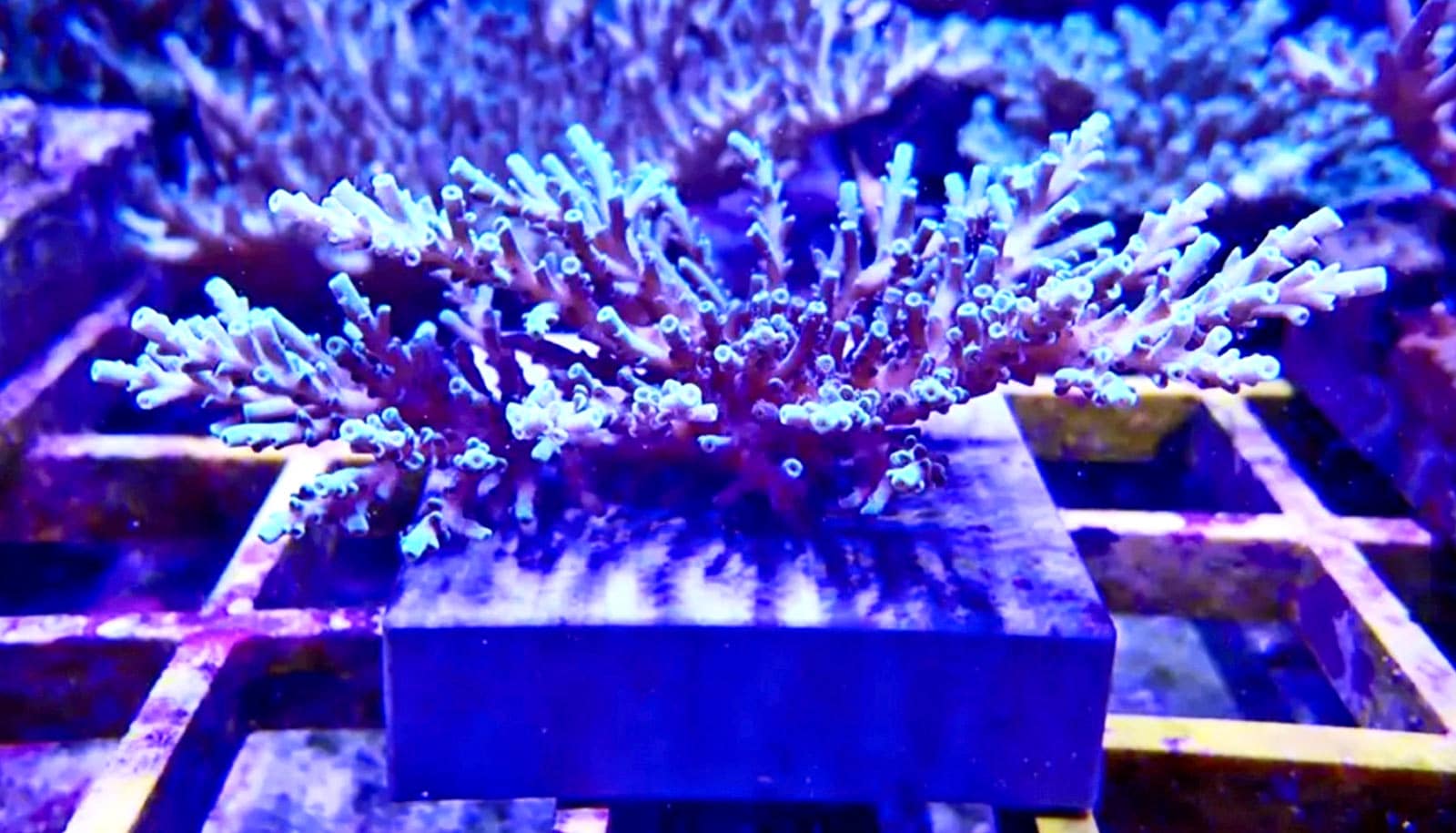

“Kelp forests along the California coast are made up of not only giant kelp, but of many other seaweed species that live beneath giant kelp,” says David Garrison, a program director in the National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences, which funds the site where the research took place.

“Kelp forests remain relatively stable because of the diversity and growth of these understory species. Understory biomass may be very important for the fish and invertebrates that live in kelp beds.”

This was one of the first studies to analyze the combined effects of different population levels on stability. “None of this was really done before,” Lamy says. “People would usually study two levels but never integrate all these levels together.”

But this perspective is crucial to develop an understanding of the ecosystem as a whole. “Natural ecosystems are like Russian dolls,” says Lamy. Stability at the regional scale is like the largest one: It’s what you see at first. But inside you can find the influence of individual species, multi-species communities, and meta-communities spanning the entire region.

The scope of the study was the result of two multi-year projects: the Santa Barbara Coastal Long Term Ecological Research project and the Santa Barbara Channel Marine Biodiversity Observation Network . The Santa Barbara Coastal LTER is part of a nationwide network of similar, long term projects on a variety of ecosystems the National Science Foundation supports. The Santa Barbara Channel MBON is aimed at integrating current biodiversity data and exploring new, more effective ways to monitor biodiversity. It was a prototype project that NASA, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, and NOAA funded and meant to expand into a larger network.

The results appear in the journal Ecology.

Source: UC Santa Barbara