Juneteenth is a celebration of the emancipation of enslaved people in the United States, but the day didn’t mark the end of Black people’s struggle for freedom, a historian argues.

This is a guest post by Susanna Lee, an associate professor of history at North Carolina State University whose work focuses largely on the Civil War and Reconstruction:

The arrival of Union troops in Galveston, Texas, in June 1865 put into effect, in the furthest reaches of the Confederacy, President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, issued two and a half years earlier.

On June 19, Major General Gordon Granger issued an order declaring a potentially revolutionary change, one that threatened the long tradition of white supremacy in the South. General Orders No. 3 declared: “all slaves are free.” June 19 is today celebrated as Juneteenth, or Emancipation Day.

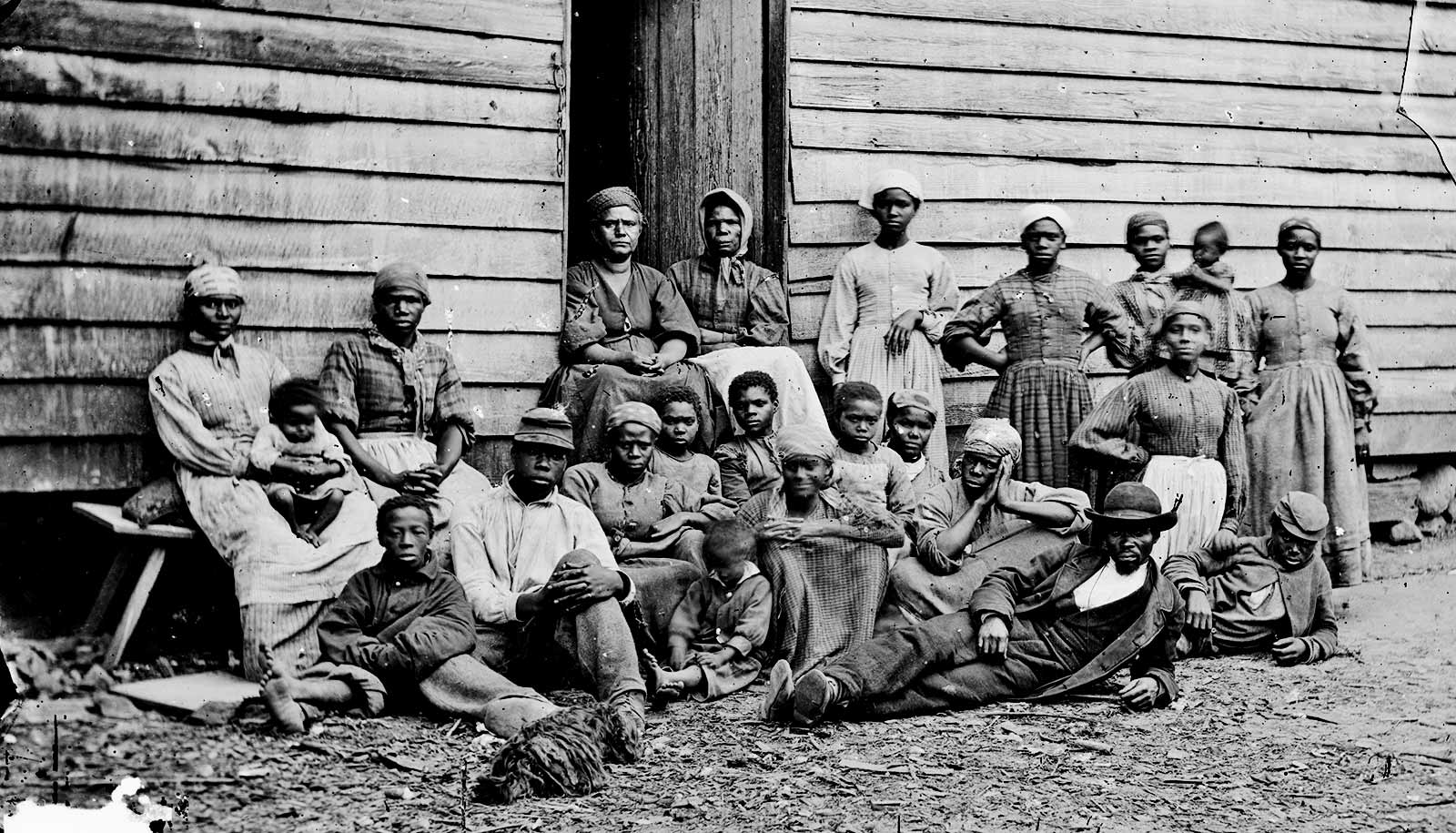

Freedom had been a long time coming for enslaved people in the Confederacy. As Union troops threatened to invade various parts of the Confederacy, enslavers contemplated ways to secure their investment in enslaved human property—including moving them further south, away from Union armies.

At the start of the war, Union officials had disclaimed any intention to interfere with the institution of slavery in the southern states. Emancipation came to the Confederacy through the efforts of enslaved people. Historians estimate that more than half a million enslaved people escaped during the war, fled to Union lines, offered their services to the Union cause, and transformed the Union army into a force of liberation.

Enslaved people greeted their emancipation with jubilation. They hoped that the end of slavery would mean the end of the auction block, the end of forced labor, the end of whippings, rapes, and other abuses. The end of an inequitable system of dehumanization and exploitation.

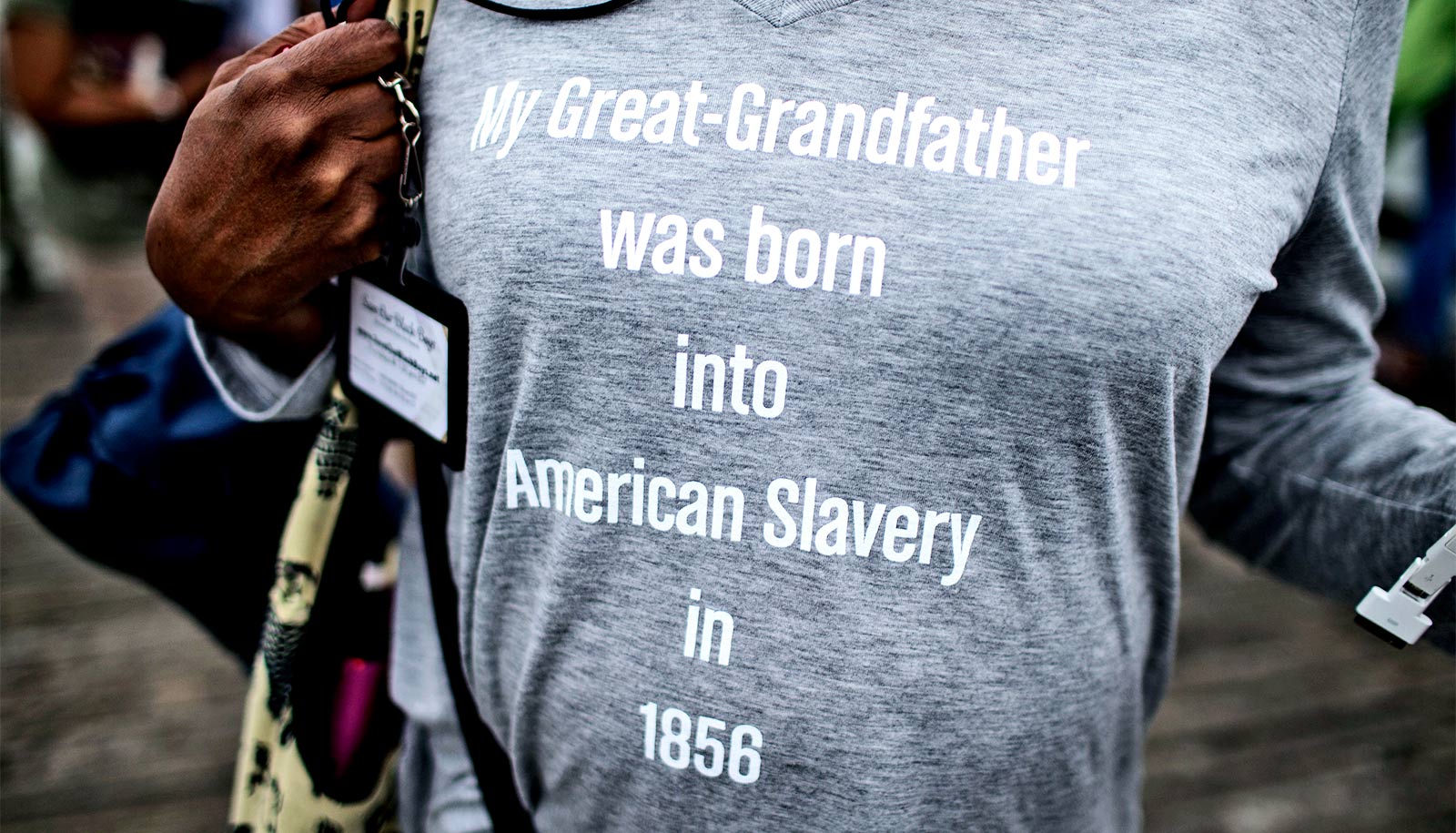

But Black people knew that freedom was not a day, or a moment. Black people on Juneteenth knew that masters and mistresses would not give them their freedom. They knew that they needed to make their own freedom. And they knew that this freedom, ever precarious, would need to be guarded with constant vigilance.

Henrietta Wood understood this, long before the man who considered himself her owner forcibly marched Wood and approximately 500 other enslaved men, women, and children from Mississippi to Texas—hundreds of miles into Confederate territory—in July 1863.

Wood had been born into bondage in Kentucky, but managed to secure her freedom in Ohio in 1848, only to be kidnapped and returned to slavery in Kentucky five years later, and then sold to Mississippi two years later. When emancipation came to Texas, Wood had already experienced freedom, a scrap quickly snatched away.

Juneteenth celebrates freedom, but it also signals the challenges faced by freedom seekers. Emancipation Day came to Texas months after the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House, and months after the fall of the Confederate capital. And it had to come to Texas in the form of Union soldiers because slave owners refused to recognize Black people as free people, “endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights.”

Wood, declared free by Granger’s orders, had few options to secure her freedom. There were few federal officials in the former Confederacy to enforce emancipation, and the federal officials in her vicinity were more sympathetic to former slaveholders than former slaves. Wood eventually signed a contract, drawn up by her former master, which she likely could not read, to labor three additional years in exchange for a quarterly wage (never paid) and transportation back to Mississippi.

Freed people would continue their struggle for freedom after the Civil War, as former slaveholders reconsolidated white supremacy in new forms of exploitation, inequality, and terror: sharecropping and convict leasing, and later lynching and segregation.

For her part, Wood filed suit against Zebulon Ward, the white man who stole her freedom, who made his fortune through Black enslaved labor before the war, and who continued to profit through Black convict labor after the war. In 1878, eight years after filing suit, and 25 years after being stolen into slavery, Wood finally won her case and received $2,500 in restitution, the largest known sum granted as reparations for slavery.

Source: NC State