The gut microbiome could be the culprit behind arthritis and joint pain that plagues people who are obese, according to a new study.

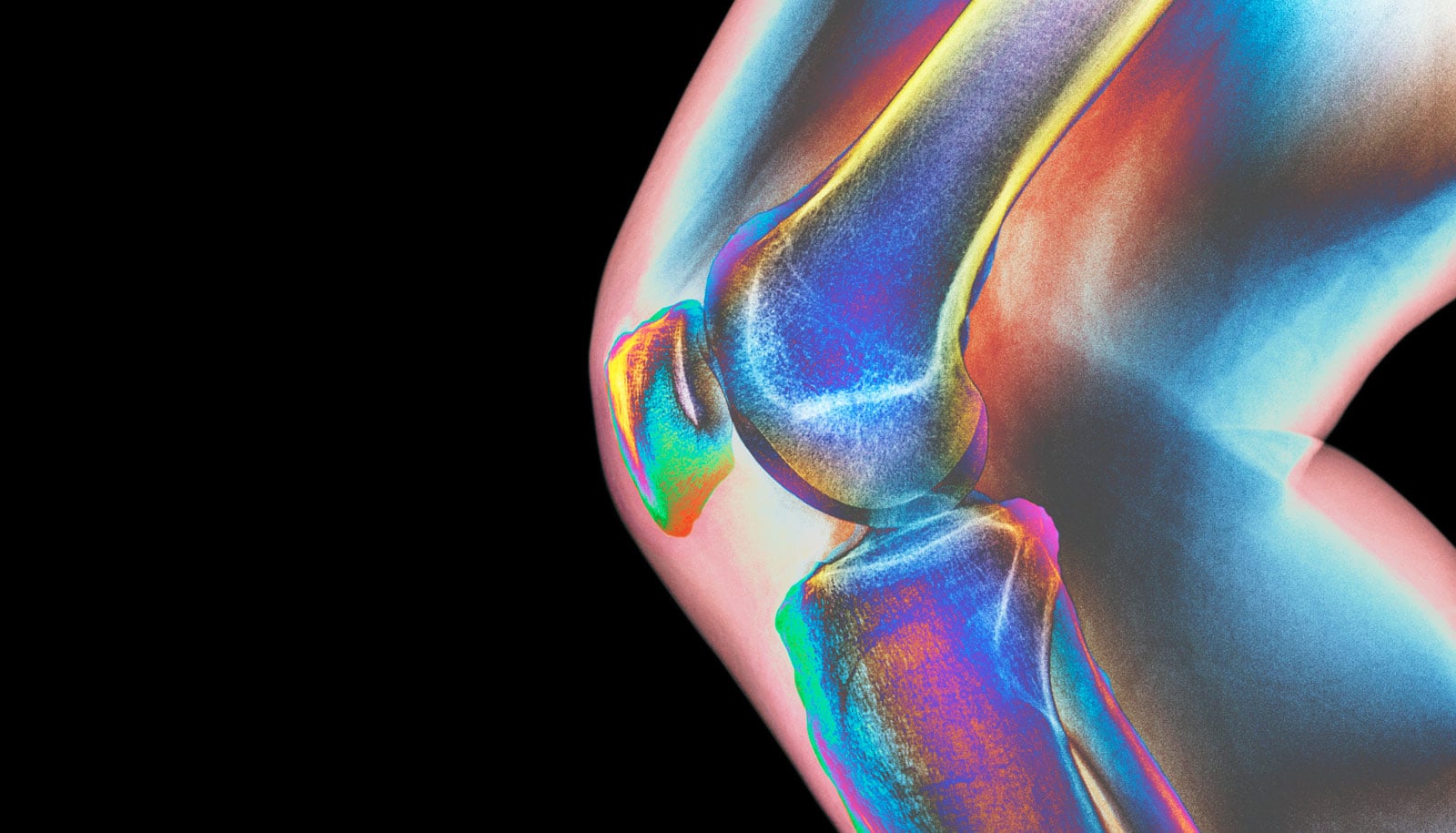

Osteoarthritis, a common side effect of obesity, is the greatest cause of disability in the US, affecting 31 million people. Sometimes called “wear and tear” arthritis, osteoarthritis in people who are obese was long assumed to simply be a consequence of undue stress on joints. But researchers now provide the first evidence that bacteria in the gut—governed by diet—could be the key driving force behind osteoarthritis.

As reported in JCI Insight, scientists found that obese mice had more harmful bacteria in their guts compared to lean mice, which caused inflammation throughout their bodies, leading to very rapid joint deterioration. While a common prebiotic supplement did not help the mice shed weight, it completely reversed the other symptoms, making the guts and joints of obese mice indistinguishable from those of lean mice.

The research team, which Michael Zuscik, associate professor of orthopedics in the Center for Musculoskeletal Research, Robert Mooney, professor of pathology and laboratory medicine, and Steven Gill, associate professor of microbiology and immunology, led, fed mice a high fat diet akin to a Western “cheeseburger and milkshake” diet.

“Cartilage is both a cushion and lubricant, supporting friction-free joint movements. When you lose that, it’s bone on bone, rock on rock.”

Just 12 weeks of the high fat diet made mice obese and diabetic, nearly doubling their body fat percentage compared to mice fed a low-fat, healthy diet. Pro-inflammatory bacteria dominated their colons, which almost completely lacked certain beneficial, probiotic bacteria, like the common yogurt additive Bifidobacteria.

The changes in the gut microbiomes of the mice coincided with signs of body-wide inflammation, including in their knees where the researchers induced osteoarthritis with a meniscal tear, a common athletic injury known to cause osteoarthritis. Compared to lean mice, osteoarthritis progressed much more quickly in the obese mice, with nearly all of their cartilage disappearing within 12 weeks of the tear.

“Cartilage is both a cushion and lubricant, supporting friction-free joint movements,” says Zuscik. “When you lose that, it’s bone on bone, rock on rock. It’s the end of the line and you have to replace the whole joint. Preventing that from happening is what we, as osteoarthritis researchers, strive to do—to keep that cartilage.”

Supplementing high-fat diets

Surprisingly, the effects of obesity on gut bacteria, inflammation, and osteoarthritis were completely prevented when researchers added a common prebiotic, called oligofructose, to the high fat diet of obese mice. The knee cartilage of obese mice that ate the oligofructose supplement was indistinguishable from that of the lean mice.

Oligofructose made obese mice less diabetic, but not thinner.

Although rodents and humans can’t digest prebiotics like oligofructose, they are welcome treats for certain types of beneficial gut bacteria, like Bifidobacteria. Colonies of those bacteria chowed down and grew, taking over the guts of obese mice and crowding out bad actors like pro-inflammatory bacteria. This, in turn, decreased systemic inflammation and slowed cartilage breakdown in the mice’s osteoarthritic knees.

Oligofructose even made the obese mice less diabetic, but there was one thing the dietary supplement didn’t change: body weight.

Obese mice that received oligofructose remained obese, bearing the same load on their joints, yet their joints were healthier. Just reducing inflammation was enough to protect joint cartilage from degeneration, supporting the idea that inflammation—not biomechanical forces—drive osteoarthritis and joint degeneration.

“That reinforces the idea that osteoarthritis is another secondary complication of obesity—just like diabetes, heart disease, and stroke, which all have inflammation as part of their cause,” says Mooney. “Perhaps, they all share a similar root, and the microbiome might be that common root.”

Don’t buy a prebiotic just yet

Though there are parallels between mouse and human microbiomes, the bacteria that protected mice from obesity-related osteoarthritis may differ from the bacteria that could help humans. Zuscik, Mooney, and Gill aim to collaborate with researchers in the Military and Veteran Microbiome: Consortium for Research and Education at the US Department of Veteran’s Affairs to move this research into humans.

The team hopes to compare veterans who have obesity-related osteoarthritis to those who don’t to further identify the connections between gut microbes and joint health. They also hope to test whether prebiotic or probiotic supplements that shape the gut microbiome can have similar effects in vets suffering from osteoarthritis as they did in mice.

“There are no treatments that can slow progression of osteoarthritis—and definitely nothing reverses it,” says first author Eric Schott, postdoctoral fellow in the CMSR and soon-to-be clinical research scientist at Solarea Bio, Inc. “But this study sets the stage to develop therapies that target the microbiome and actually treat the disease.”

Source: University of Rochester