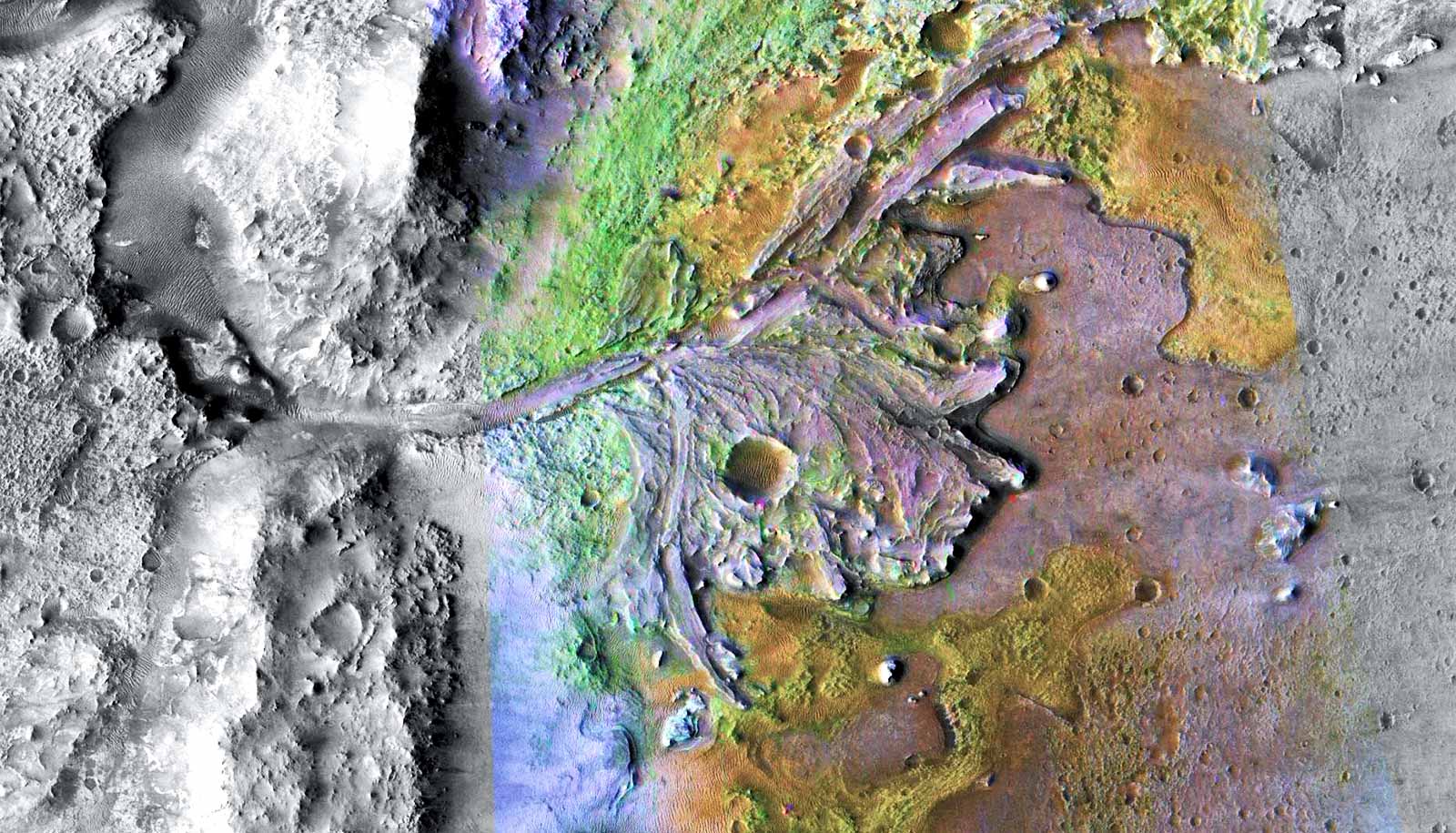

A new analysis of satellite imagery supports the hypothesis that the Jezero crater on Mars could be a good place to look for markers of life.

NASA’s Perseverance rover, expected to launch in July 2020, will land at the Jezero crater.

Undulating streaks of land visible from space reveal rivers once coursed across the Martian surface—but for how long did the water flow? Enough time to record evidence of ancient life, the new study shows.

When researchers modeled the length of time it took to form the layers of sediment in a delta an ancient river deposited as it poured into the crater, they concluded that if life once existed near the Martian surface, traces of it could have been captured within the delta layers.

“There probably was water for a significant duration on Mars and that environment was most certainly habitable, even if it may have been arid,” says lead author Mathieu Lapôtre, an assistant professor of geological sciences at Stanford University’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth).

“We showed that sediments were deposited rapidly and that if there were organics, they would have been buried rapidly, which means that they would likely have been preserved and protected.”

Formation of Jezero crater

NASA selected Jezero crater for its next rover mission partly because the site contains a river delta. Researchers know that river deltas on Earth effectively preserve organic molecules associated with life.

But without an understanding of the rates and durations of delta-building events, the analogy remained speculative.

The new research in AGU Advances offers guidance for sample recovery in order to better understand the ancient Martian climate and duration of the delta formation for NASA’s Perseverance Rover to Mars, which will launch as part of the first Mars sample return mission.

The study incorporates a recent discovery the researchers made about Earth: Single-threaded sinuous rivers that don’t have plants growing over their banks move sideways about 10 times faster than those with vegetation.

Based on the strength of Mars’ gravity, and assuming the red planet did not have plants, the scientists estimate that the delta in Jezero crater took at least 20 to 40 years to form, but that formation was likely discontinuous and spread out across about 400,000 years.

“This is useful because one of the big unknowns on Mars is time,” Lapôtre says. “By finding a way to calculate rate for the process, we can start gaining that dimension of time.”

Because single-threaded, meandering rivers are most often found with vegetation on Earth, their occurrence without plants remained largely undetected until recently. It was thought that before the appearance of plants, only braided rivers, made up of multiple interlaced channels, existed.

Evolution of life on Earth

Now that researchers know to look for them, they have found meandering rivers on Earth today where there are no plants, such as in the McLeod Springs Wash in the Toiyabe basin of Nevada.

“This specifically hadn’t been done before because single-threaded rivers without plants were not really on anyone’s radar,” Lapôtre says. “It also has cool implications for how rivers might have worked on Earth before there were plants.”

The researchers also estimated that wet spells conducive to significant delta buildup were about 20 times less frequent on ancient Mars than they are on Earth today.

“People have been thinking more and more about the fact that flows on Mars probably were not continuous and that there have been times when you had flows and other times when you had dry spells,” Lapôtre says. “This is a novel way of putting quantitative constraints on how frequently flows probably happened on Mars.”

Findings from Jezero crater could aid our understanding of how life evolved on Earth. If life once existed there, it likely didn’t evolve beyond the single-cell stage, scientists say. That’s because Jezero crater formed over 3.5 billion years ago, long before organisms on Earth became multicellular.

If life once existed at the surface, some unknown event that sterilized the planet stalled its evolution. That means the Martian crater could serve as a kind of time capsule preserving signs of life as it might once have existed on Earth.

“Being able to use another planet as a lab experiment for how life could have started somewhere else or where there’s a better record of how life started in the first place—that could actually teach us a lot about what life is,” Lapôtre says. “These will be the first samples that we’ve seen as a rock on Mars and then brought back to Earth, so it’s pretty exciting.”

Source: Stanford University