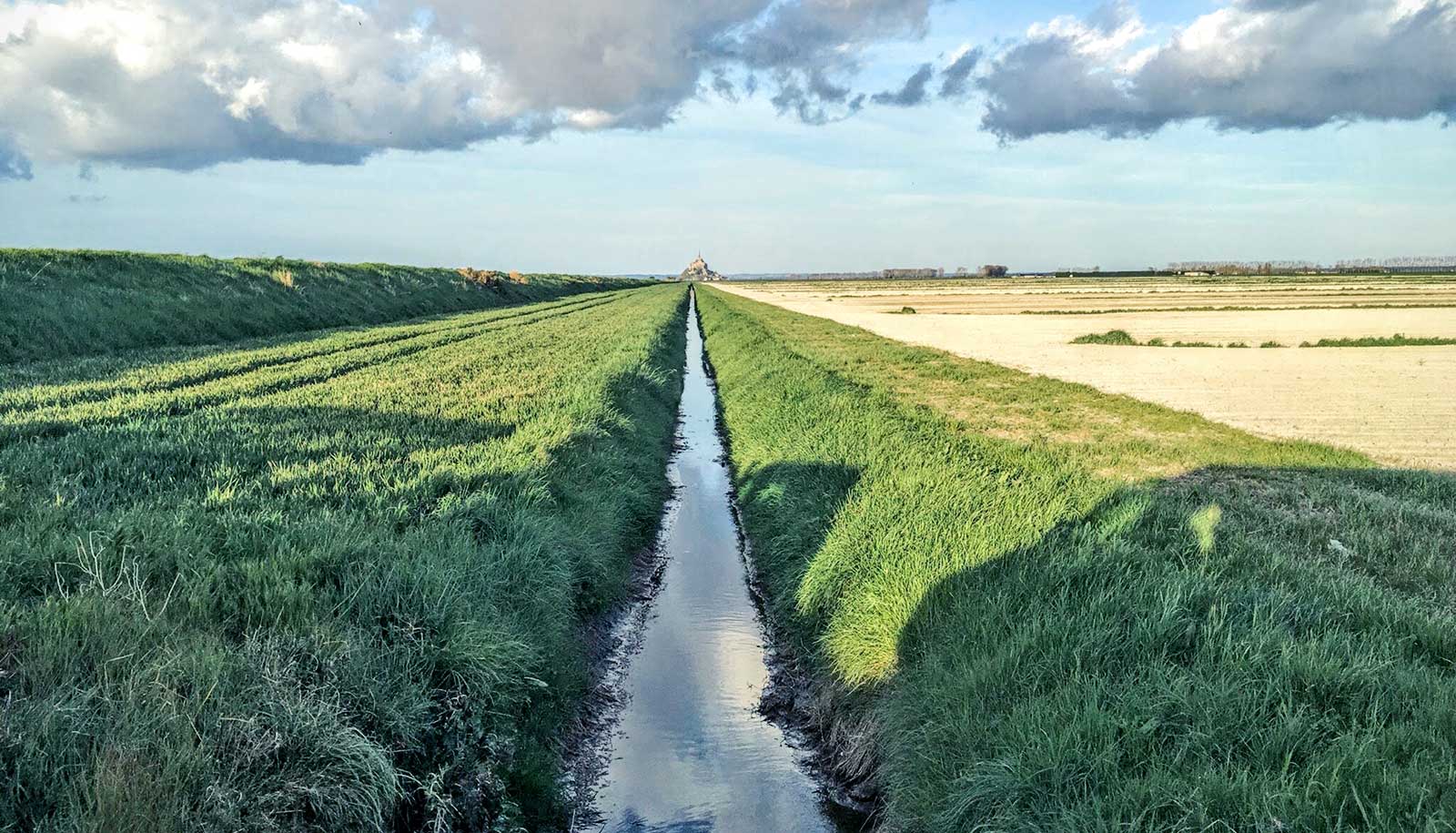

A new study shows how irrigation affects regional climates and environments around the world, illuminating how and where the practice is both untenable and beneficial.

The analysis also points to ways to improve assessments in order to achieve sustainable water use and food production in the future.

“Even though irrigation covers a small fraction of the Earth, it has a significant impact on regional climate and environments—and is either already unsustainable, or verging on towards scarcity, in some parts of the world,” says Sonali Shukla McDermid, an associate professor in the environmental studies department at New York University and lead author of the paper in Nature Reviews Earth and Environment.

“But because irrigation supplies 40% of the world’s food, we need to understand the complexities of its effects so we can reap its benefits while reducing negative consequences.”

Irrigation, which is primarily used for agricultural purposes, accounts for roughly 70% of global freshwater extractions from lakes, rivers, and other sources, amounting to 90% of the world’s water usage.

Previous estimates suggest that more than 3.6 million square kilometers—or just under 1.4 million square miles—of the Earth’s land are currently irrigated. Several regions, including the US High Plains states, such as Kansas and Nebraska, California’s Central Valley, the Indo-Gangetic Basin spanning several South Asian countries, and northeastern China, are the world’s most extensively irrigated and also display among the strongest irrigation impacts on the climate and environment.

While work exists to document some impacts of irrigation on specific localities or regions, it’s been less clear if there are consistent and strong climate and environmental impacts across global irrigated areas—both now and in the future.

To address this, 38 researchers from the US, Australia, Austria, Belgium, France, India, Italy, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan analyzed more than 200 previous studies—an examination that captured both present-day effects and projected future impacts.

Their review pointed to both positive and negative effects of irrigation, including:

- Irrigation can cool daytime temperatures substantially and can also change how agroecosystems store and cycle carbon and nitrogen. While this cooling can help combat heat extremes, irrigation water can also humidify the atmosphere and can result in the release of greenhouse gasses, such as powerful methane from rice.

- The practice annually withdraws an estimated 2,700 cubic kilometers from freshwater sources, or nearly 648 cubic miles, which is more water than is held by Lake Erie and Lake Ontario combined. In many areas, this usage has reduced water supplies, particularly groundwater, and has also contributed to the runoff of agricultural inputs, such as fertilizers, into water supplies.

- Irrigation can also affect precipitation in some areas, depending on the locale, season, and prevailing winds.

The researchers also propose ways to improve irrigation modeling—changes that would result in methods to better assess ways to achieve sustainable water and food production into the future.

These largely center on adopting more rigorous testing of models as well as more and better ways of identifying and reducing uncertainties associated with both the physical and chemical climate processes and—importantly—human decision-making. The latter could be done with more coordination and communication between scientists and water stakeholders and decision-makers when developing irrigation models.

“Such assessments would allow scientists to more comprehensively investigate interactions between several, simultaneously changing conditions, such as regional climate change, biogeochemical cycling, water resource demand, food production, and farmer household livelihoods—both now and in the future,” says McDermid.

The National Science Foundation, the National Research Foundation of Korea, and the Japan Science and Technology Agency funded the work.

Source: NYU