Robotic fish can be a valuable tool in the fight against one of the world’s most problematic invasive species, the mosquitofish, researchers report.

Invasive species control is notoriously challenging, especially in lakes and rivers where native fish and other wildlife have limited options for escape.

Soaring mosquitofish populations in freshwater lakes and rivers worldwide have decimated native fish and amphibian populations, and attempts to control the species through toxicants or trapping often fail or cause harm to local wildlife.

Stress as a weapon against invasive species

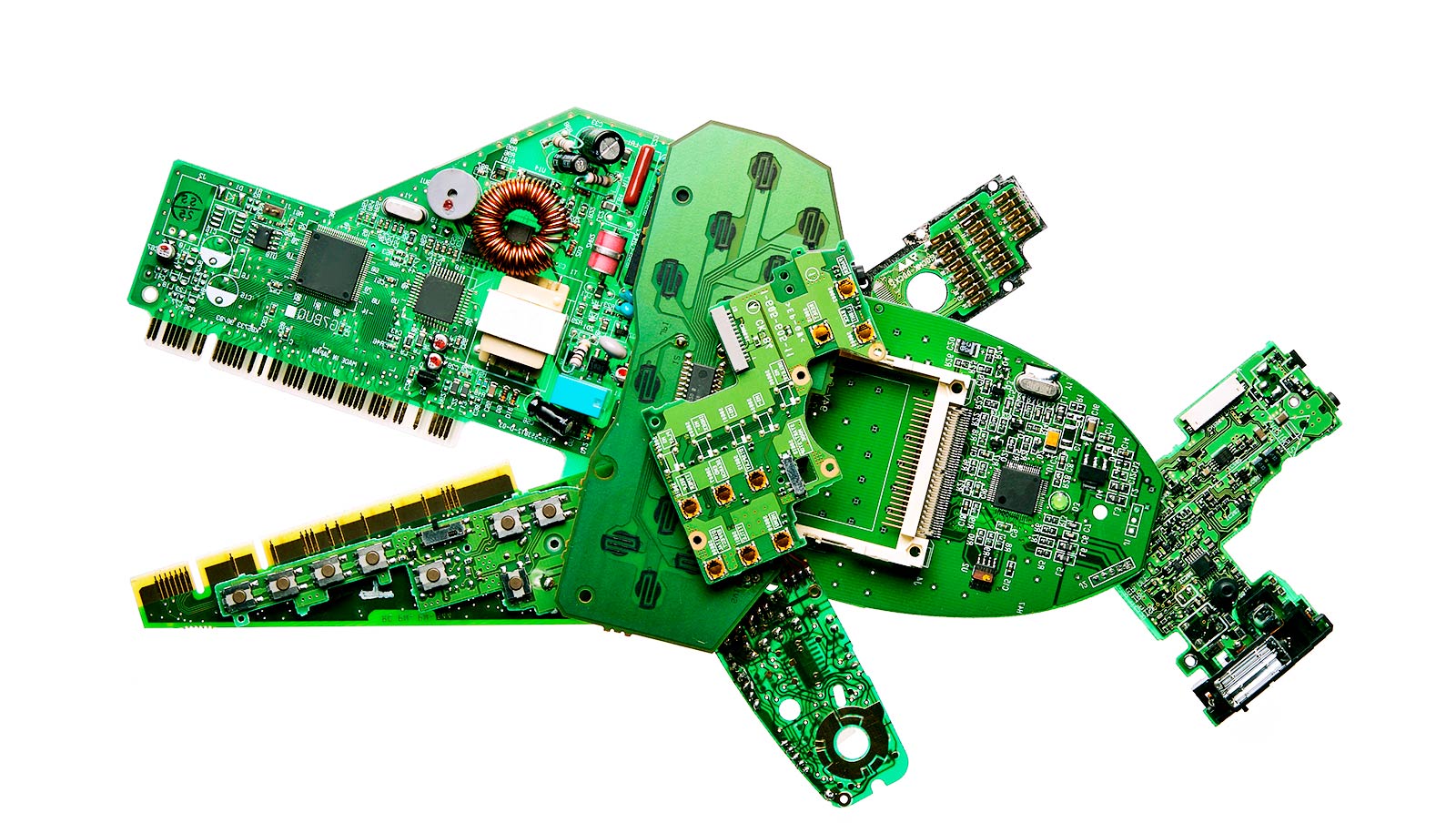

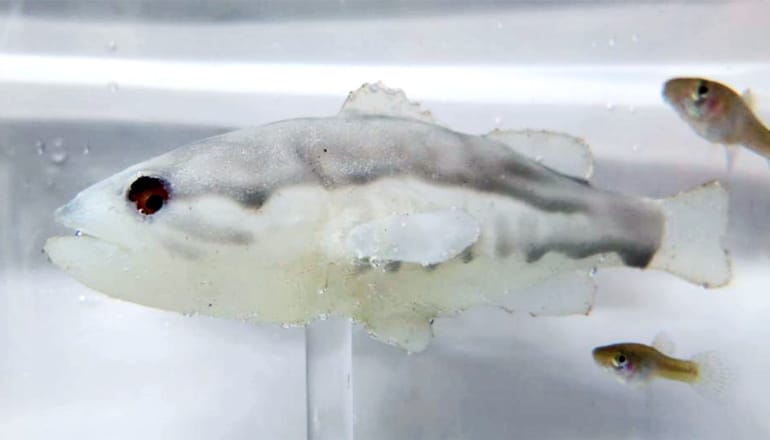

Researchers have published the first experiments to gauge the ability of a biologically inspired robotic fish to induce fear-related changes in mosquitofish. Their findings indicate that even brief exposure to a robotic replica of the mosquitofish’s primary predator—the largemouth bass—can provoke meaningful stress responses in mosquitofish, triggering avoidance behaviors and physiological changes associated with the loss of energy reserves, potentially translating into lower rates of reproduction.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study using robots to evoke fear responses in this invasive species,” says Maurizio Porfiri, professor at the Tandon School of Engineering at New York University. “The results show that a robotic fish that closely replicates the swimming patterns and visual appearance of the largemouth bass has a powerful, lasting impact on mosquitofish in the lab setting.”

The team exposed groups of mosquitofish to a robotic largemouth bass for one 15-minute session per week for six consecutive weeks. The robot’s behavior varied between trials, spanning several degrees of biomimicry. Notably, in some trials, the researchers programmed the robot to incorporate real-time feedback based on interactions with live mosquitofish and to exhibit “attacks” typical of predatory behavior—a rapid increase in swimming speed.

Researchers tracked interactions between the live fish and the replica in real time and analyzed them to reveal correlations between the degree of biomimicry in the robot and the level of stress response the live fish exhibited. Fear-related behaviors in mosquitofish include freezing (not swimming), hesitancy in exploring open spaces that are unfamiliar, and potentially dangerous, and erratic swimming patterns.

Freaked out fish

The researchers also measured physiologic parameters of stress response, anesthetizing the fish weekly to measure their weight and length. Decreases in weight indicate a stronger anti-predator response and result in lower energy reserves. Fish with lower reserves are less likely to survive long and devote energy toward future reproduction—factors with strong implications for population management in the wild.

Fish exposed to robotic predators that most closely mimicked the aggressive, attack-oriented swimming patterns of real-life predators displayed the highest levels of behavioral and physiological stress responses.

“Further studies are needed to determine if these effects translate to wild populations, but this is a concrete demonstration of the potential of robotics to solve the mosquitofish problem,” says lead author Giovanni Polverino, a fellow in the biological sciences department at the University of Western Australia. “We have a lot more work going on between our schools to establish new, effective tools to combat the spread of invasive species.”

Porfiri’s Dynamical Systems Laboratory is known for previous work using biomimetic robots alongside live fish to tease out the mechanisms of many collective animal behaviors, including leadership, mating preferences, and even the impact of alcohol on social behaviors. In addition to developing robots that offer fully controllable stimuli for studying animal behavior, the biomimetic robots minimize use of experimental animals.

The paper appears in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Additional researchers came from NYU and the University of Western Australia. The National Science Foundation and the Forrest Research Foundation supported the research.

Source: New York University