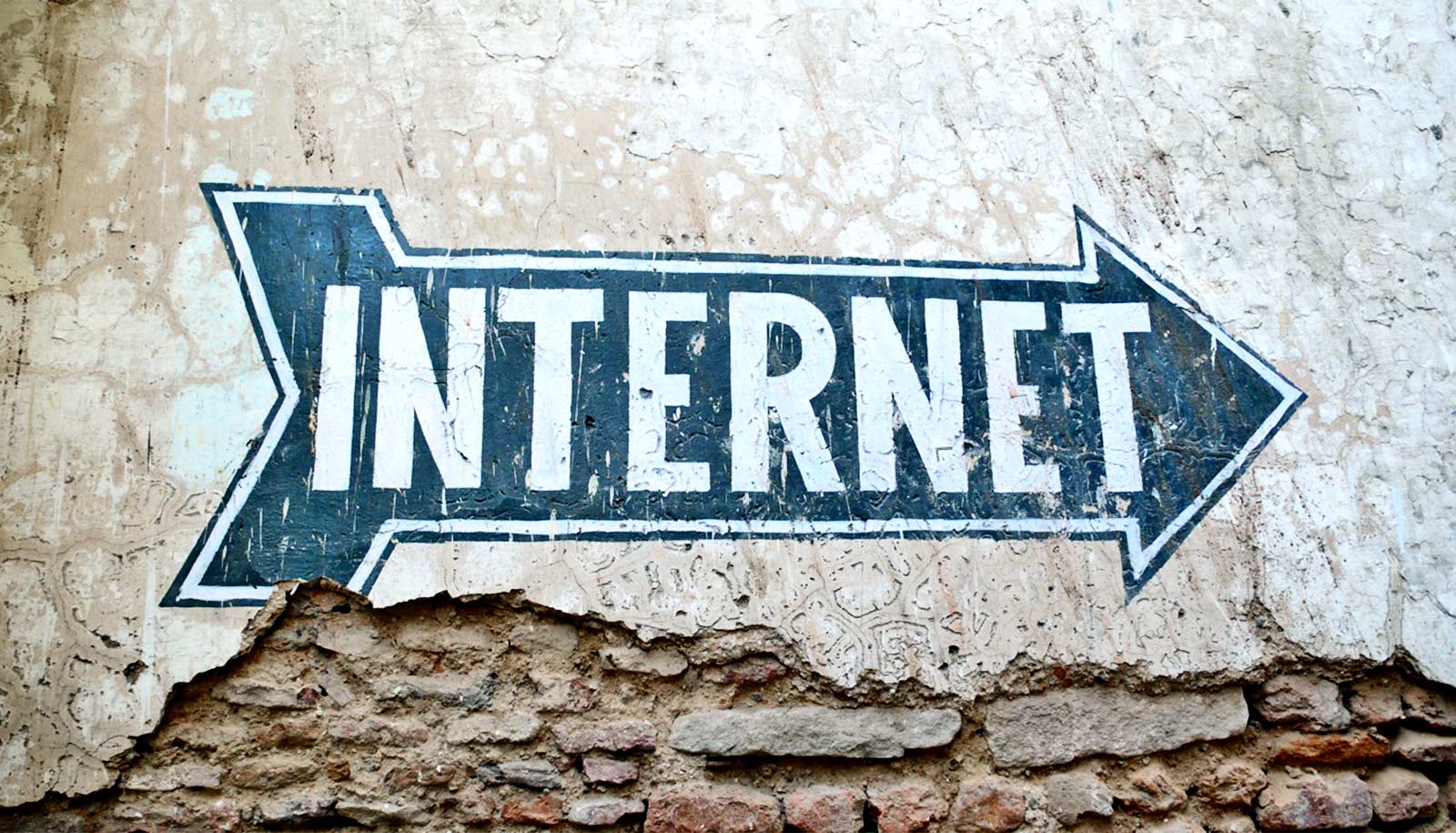

A new website can help you understand the security risks internet-connected devices might bring into your home.

Consumer-grade internet of things (IoT) devices aren’t exactly known for having tight security practices. To save purchasers from finding that out the hard way, researchers have done security assessments of representative devices, awarding scores ranging from 28 (an F) up to 100.

Their site, yourthings.info, shows rankings for 45 devices, though researchers have evaluated a total of 74. That’s hardly a complete roundup of the tens of thousands of devices available, but the big idea behind the project is to help consumers understand important issues before connecting a new IoT helper to their home networks.

“A lot of people who purchase these devices don’t fully understand the risks associated with installing them in their homes,” says Omar Alrawi, a graduate research assistant at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “We want to provide insight by providing security ratings for the devices we have tested.”

Vulnerabilities in internet-connected devices

Voice-activated personal digital assistants are among the most common home IoT devices, but if not properly installed, they can provide unwanted access to the home networks to which they are connected, warns Manos Antonakakis, a cybersecurity researcher and associate professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

“If you have an IoT app that is vulnerable, whoever has access to that app not only has access to your personal information, but could also jump into your home and eavesdrop on your conversations,” he says. “Anything that is connected in the home in proximity to the personal assistant could also interact with it. If there is vulnerable software running on the device, it could be exploited within the home network.”

One problem is that most home networks were set up for simple tasks like sharing printers, so they lack the kind of security controls found on enterprise systems at businesses, notes Chaz Lever, a research engineer in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

“The home network is beginning to look a lot like enterprise networks with a range of services that have to be protected,” Lever says. “But the average consumer is not going to be equipped to do that. They don’t have an IT staff that is doing audits and securing the devices. If these devices are not secure out of the box and there aren’t easy ways to secure them, they can open the home up to a new vector of attacks.”

Risk assessment

To give consumers helpful advice, the researchers developed a framework for analyzing the devices’ security components. In what is believed to be the first effort to objectively assess the risks of IoT equipment, they examined the devices themselves, how the devices communicate with cloud servers, the applications running on the devices, and the cloud-based endpoints.

“The more services running on the device, the higher the probability that some of them will be vulnerable to attack,” Antonakakis says. “Providing many services may be attractive from a marketing perspective, but if you have multiple services, the risk increases.”

In their study of IoT devices, the researchers found wide variations in security depending on the manufacturer. In some cases, equipment made by small and lesser-known companies performed better than devices made by larger companies.

“There are some devices that do security really well, and other manufacturers should learn from those exemplary devices,” Alrawi says. “We saw the full spectrum of good and bad, and sometimes we were surprised at the results of our evaluation.”

Because manufacturers design these products so that consumers can install them, these IoT devices must be easy to use. But ease of use can be the enemy of security. An example is a service known as UPnP, which makes devices known to the network during installation so communications can be established.

But a device announcing itself on the network can attract attackers, Lever notes. “It’s helpful for the devices to communicate what they do, but that opens up vulnerabilities. The choice of protocols affects not only the device, but also the security of the network on which it is running.”

Patching your refrigerator

Internet-connected light bulbs are unlikely to have a long service life, but that’s not the case with expensive appliances like internet-connected refrigerators. Antonakakis worries that these devices could become security risks without regular updates.

“Ideally, the consumer shouldn’t have to be aware that their refrigerator needs updates that have to be downloaded to the device,” he says. “We want that to happen automatically and securely. Why should anyone have to know how to patch their refrigerator?”

While the notion of hacking a slow cooker might seem amusing, the devices have heating elements that could cause a fire if a malicious actor turned up the temperature. Attacks can also affect more than a homeowner. In 2016, the Mirai botnet took advantage of unsecured internet-connected cameras—many of them baby monitors—to create a massive distributed denial of service attack that left much of the internet unavailable.

Beyond educating consumers, the researchers hope to encourage better security by device manufacturers by tracking security trends over time.

“We hope to inspire both technical and policy next steps,” says Antonakakis. “There is a need for establishing policy and standards. We want to raise the security level of all these devices. There is a lot more that could be done.”

Fabrian Monrose from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was also a member of the research team.

The US Department of Commerce, the National Science Foundation, and the Air Force Research Laboratory/Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency supported the research. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors.

Source: Georgia Tech