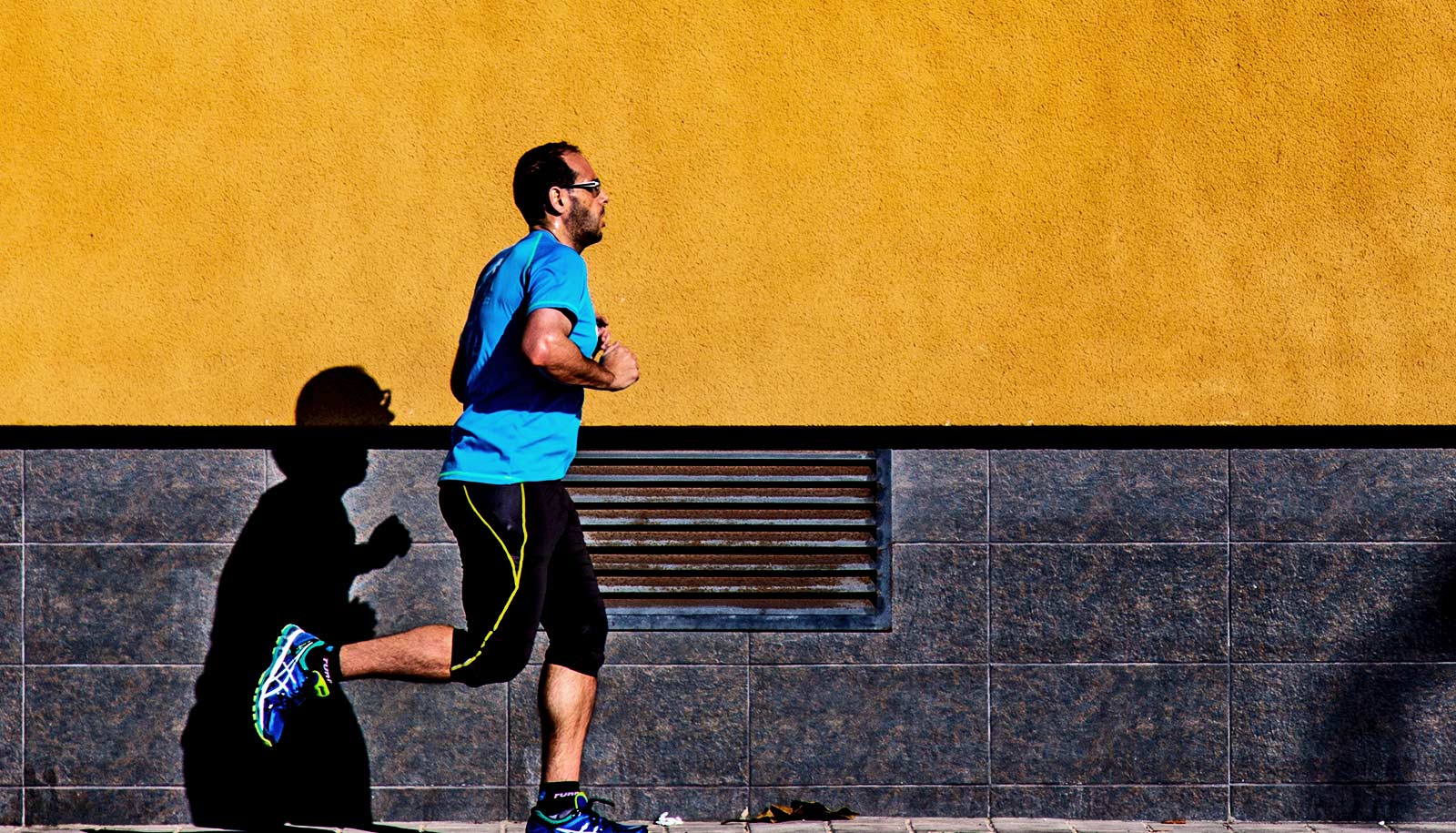

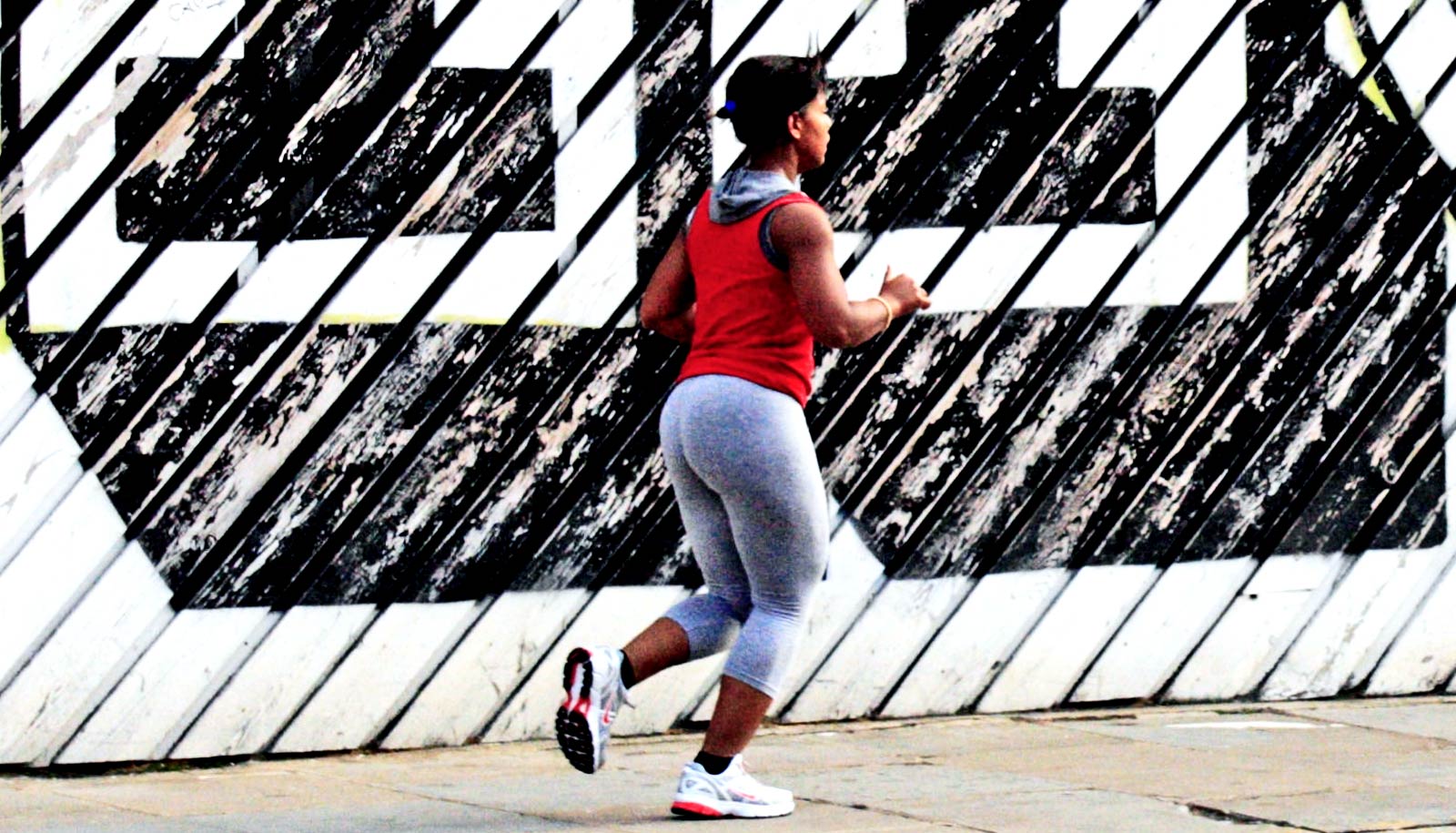

Working out with more intensity than, say, walking 10,000 steps over the course of a day—drastically improves a person’s fitness, compared to milder forms of exercise, researchers report.

Exercise is healthy. That is common knowledge. But just how rigorous should that exercise be in order to really impact a person’s fitness level? And, if you sit all day at a desk, but still manage to get out and exercise, does that negate your six, seven, or eight hours of sedentary behavior?

These were the sort of questions Matthew Nayor and his team at Boston University School of Medicine set out to answer in the largest study to date aimed at understanding the relationship between regular physical activity and a person’s physical fitness.

The study of approximately 2,000 participants from the Framingham Heart Study appears in the European Heart Journal.

“By establishing the relationship between different forms of habitual physical activity and detailed fitness measures,” Nayor says, “we hope that our study will provide important information that can ultimately be used to improve physical fitness and overall health across the life course.”

Nayor, a Boston University School of Medicine assistant professor of medicine, is also a cardiologist specializing in heart failure at Boston Medical Center, the university’s primary teaching hospital and the city of Boston’s safety net hospital.

Here, Nayor explains the results of the study and what people should know about exercise in relation to fitness:

People might see a study that finds that moderate to vigorous activity is the best way to improve fitness, and think, isn’t that obvious? But your research is more specific than that, so can you tell us what was surprising or perhaps revealing about your work?

While there is a wealth of evidence supporting the health benefits of both physical activity and higher levels of fitness, the actual links between the two are less well understood, especially in the general population (as opposed to athletes or individuals with specific medical problems). Our study was designed to address this gap, but we were also interested in answering several specific questions.

First, we wondered how different intensities of physical activity might lead to improvements in the body’s responses during the beginning, middle, and peak of exercise. We expected to find that higher amounts of moderate-vigorous physical activity, like exercise, would lead to better peak exercise performance, but we were surprised to see that higher intensity activity was also more efficient than walking in improving the body’s ability to start and sustain lower levels of exertion.

We were also uncertain whether the number of steps per day or less time spent sedentary would truly impact peak fitness levels. We found that they were associated with higher fitness levels in our study group. These findings were consistent across categories of age, sex, and health status, confirming the relevance of maintaining physical activity [throughout the day] for everyone.

Second, we asked, how do different combinations of the three activity measures contribute to peak fitness? Intriguingly, we observed that individuals with higher-than-average steps per day, or moderate-vigorous physical activity, had higher-than-average fitness levels, regardless of how much time they spent sedentary. So, it seems that much of the negative effect that being sedentary has on fitness may be offset by also having higher levels of activity and exercise.

Our third question was, are more recent physical activity habits more important than previous exercise habits in determining current levels of fitness? Interestingly, we found that participants with high activity values at one assessment and low values at another assessment, performed eight years apart, had equivalent levels of fitness, whether or not the high value coincided with the fitness testing. This suggests that there may be a “memory effect” of previous physical activity on current levels of fitness.

A lot of people wear Fitbits or their Apple Watch to track their daily step counts these days, and they might think, hey, I did 10,000 steps today! But it sounds like your research suggests that while walking is valuable, it’s not the same as exercise?

Well, I think we need to be a little careful with this interpretation. It is important to note that higher steps were associated with higher fitness levels in our study, which is reassuring, especially for older individuals or those with medical conditions that may prohibit higher levels of exertion. There is also ample evidence from other studies that higher step counts are associated with a host of favorable health outcomes. So, I would not want to dissuade people from following their step counts.

However, if your goal is to improve your fitness level, or to slow down the inescapable decline in fitness that occurs with aging, performing at least a moderate level of exertion [through intentional exercise] is over three times more efficient than just walking at a relatively low cadence.

Where is that line? When does exercise go from moderate to rigorous, for people who might be wondering if they are doing enough?

We used definitions from prior studies that categorized a cadence of 60-99 steps/minute as low-level exertion, while 100-129 steps/minute is generally considered to be indicative of moderate physical activity and greater than 130 steps/minute is considered vigorous.

These step counts may need to be a bit higher in younger individuals. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend 150-300 minutes/week of moderate intensity or 75-150 minutes/week of vigorous intensity exercise. However, this upper limit is really a guidance meant to encourage people to exercise. In our study, we did not observe any evidence of a threshold beyond which higher levels of activity were no longer associated with greater fitness.

Can you explain in some detail how the results of your study were achieved, studying participants in the Framingham Heart Study?

Thank you for this question and for the opportunity to thank the Framingham Heart Study participants. It is only through their voluntary participation over three generations now that studies such as ours are possible.

For our study, we analyzed data from participants of the Third Generation cohort (literally the grandchildren of the original participants, in many cases) and the multiracial sample. At the most recent study visit in 2016–2019, we performed cardiopulmonary exercise tests (CPETs) on stationary cycles for comprehensive fitness evaluations. CPETs are the “gold standard” assessment of fitness and involve exercise testing with a face mask or mouthpiece to measure the oxygen that is breathed in and the carbon dioxide that’s breathed out during exercise.

You may have seen professional endurance athletes (such as cyclists) performing similar tests during training sessions. Participants also took home accelerometers, which were worn on belts around their waist for eight days after their study visit. Accelerometers were worn at the recent study visit and at the prior visit eight years earlier, and information was compared.

Do you have your own exercise routine, where you are consciously thinking of moderate versus rigorous, and trying to find that balance?

Well, I’m certainly not a competitive athlete, but I try to stay active. One aspect of our results that I keep coming back to is the finding that higher levels of sedentary time can be offset by dedicated exercise. I find this reassuring—especially during the pandemic when many of us are spending even more time seated in front of a computer—that my daily run or Peloton class is serving to at least preserve my fitness level.

Support for the work comes from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; the American Heart Association; a Career Investment Award from the BU School of Medicine’s Department of Medicine; the Evans Medical Foundation; and the Jay and Louis Coffman Endowment from BU School of Medicine’s Department of Medicine.

Source: Doug Most for Boston University