Satellite data over the Southern Hemisphere clarifies the makeup of global clouds since the Industrial Revolution—and suggests clouds then were not so different than clouds today, according to a new study.

The research tackles one of the largest uncertainties in today’s climate models—the long-term effect of tiny atmospheric particles on climate change.

The researchers used remote, pristine parts of the Southern Hemisphere as a window into the early-industrial atmosphere.

The team compared satellite measurements of cloud droplet concentration in the atmosphere over the Northern Hemisphere—now heavily polluted with today’s industrial aerosols—and over the relatively pristine Southern Ocean. They used this to measure how particles from pollution may have affected Earth’s temperature since 1850.

The results in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggest that early industrial aerosol concentrations and cloud droplet numbers were much higher than many global climate models estimate.

This could mean that human-generated atmospheric aerosols, or particulate pollution, is not damping the warming from carbon dioxide as much as some climate models estimate. The study suggests that the cooling effect of pollution is likely to be more moderate.

“One of the biggest surprises for us was how high the concentration of cloud droplets is in Southern Ocean clouds,” says co-lead author Isabel McCoy, a doctoral student in atmospheric sciences at the University of Washington.

Cloud droplets

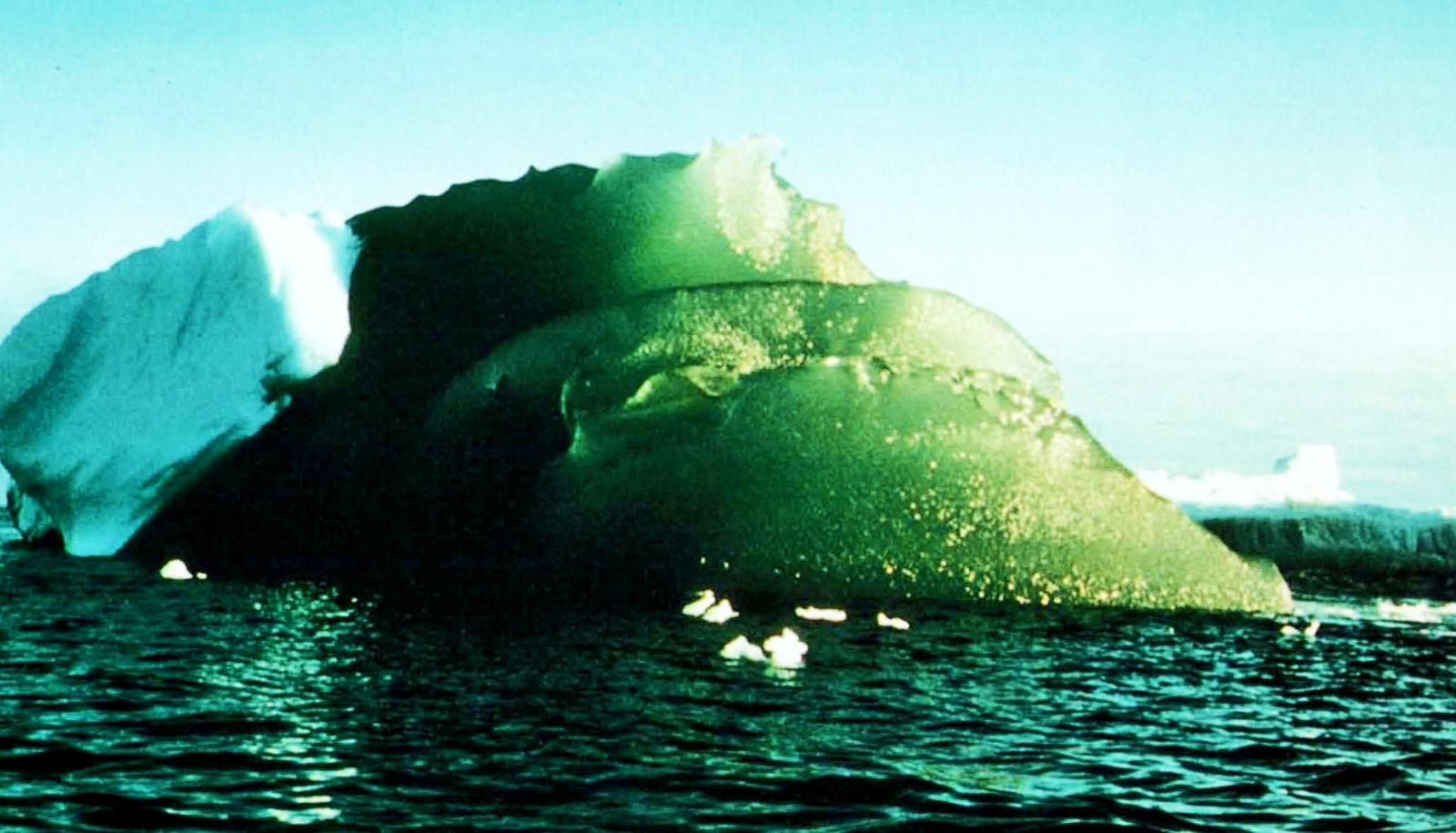

The Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica has few aerosol particles from human activity, but the cloud droplet concentration remains high, especially in summer.

“The way that the cloud droplet concentration increases in summertime tells us that ocean biology is playing an important role in setting cloud brightness in unpolluted oceans, now and in the past,” McCoy says.

“We see high cloud-droplet concentrations in satellite and aircraft observations, but not in climate models,” she says. “This suggests that there are gaps in the model representation of aerosol-cloud interactions and aerosol-production mechanisms in pristine environments.”

Climate models represent the global warming effect of greenhouse gases as well as the cooling effects of atmospheric aerosols. Human-made sources such as emissions from cars and industry, as well as natural sources, such as phytoplankton and sea spray, produce the tiny particles that make up these aerosols.

The particles can influence sunlight and heat flow within the atmosphere as well as interact with clouds. One way the particles affect clouds is by increasing the cloud droplet concentration, causing the clouds to reflect more sunlight back to space.

Little is known, however, about how aerosol concentrations have changed over the industrial era. This restricts the climate models’ ability to accurately estimate the long-term effects of aerosols on global temperatures.

“Limitations in our ability to measure aerosols in the early-industrial atmosphere have made it hard to reduce uncertainties in how much warming there will be in the 21st century,” says co-lead author Daniel McCoy, who completed the work at the University of Leeds and is now an assistant professor at the University of Wyoming.

Unpolluted atmosphere

Daniel McCoy, a former University of Washington doctoral student and Isabel’s brother, authored a previous study showing that biological activity in the Southern Ocean influences clouds more than expected.

“Ice cores provide carbon dioxide concentrations from millennia in the past, but aerosols don’t hang around in the same way,” he says. “One way that we can try to look back in time is to examine a part of the atmosphere that we haven’t polluted yet.

“Isabel proposed this work based on what she saw flying out of Tasmania as part of the University of Washington team participating in the Southern Ocean Clouds, Radiation, Aerosol Transport Experimental Study (SOCRATES). These observations were supported by other recent field data and this grew our confidence in what we had been seeing from space.”

Measurements over the Southern Ocean and other remote locations can ultimately help improve global climate models.

“As we continue to observe pristine environments through satellite, aircraft, and ground platforms, we can improve the representation of the complex mechanisms controlling cloud brightness in climate models and increase the accuracy of our climate projections,” Isabel McCoy says.

Additional coauthors are from the University of Washington, the University of Leeds, the University of Oxford, Stockholm University, Carnegie-Mellon University, and NASA. The National Science Foundation, NASA, the UK Natural Environment Research Council, and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program funded the work.

Source: University of Washington