Researchers have discovered a new marine reptile.

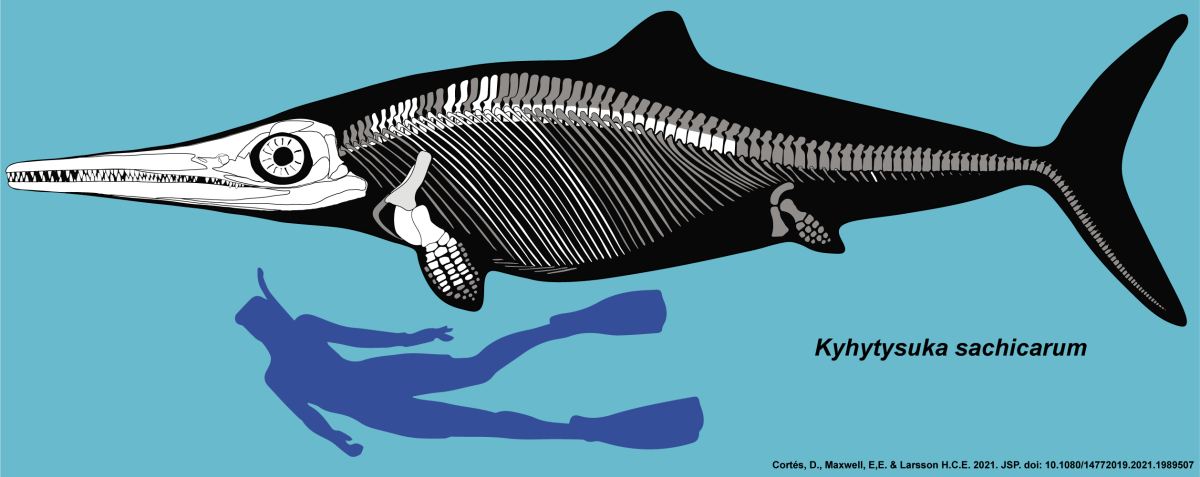

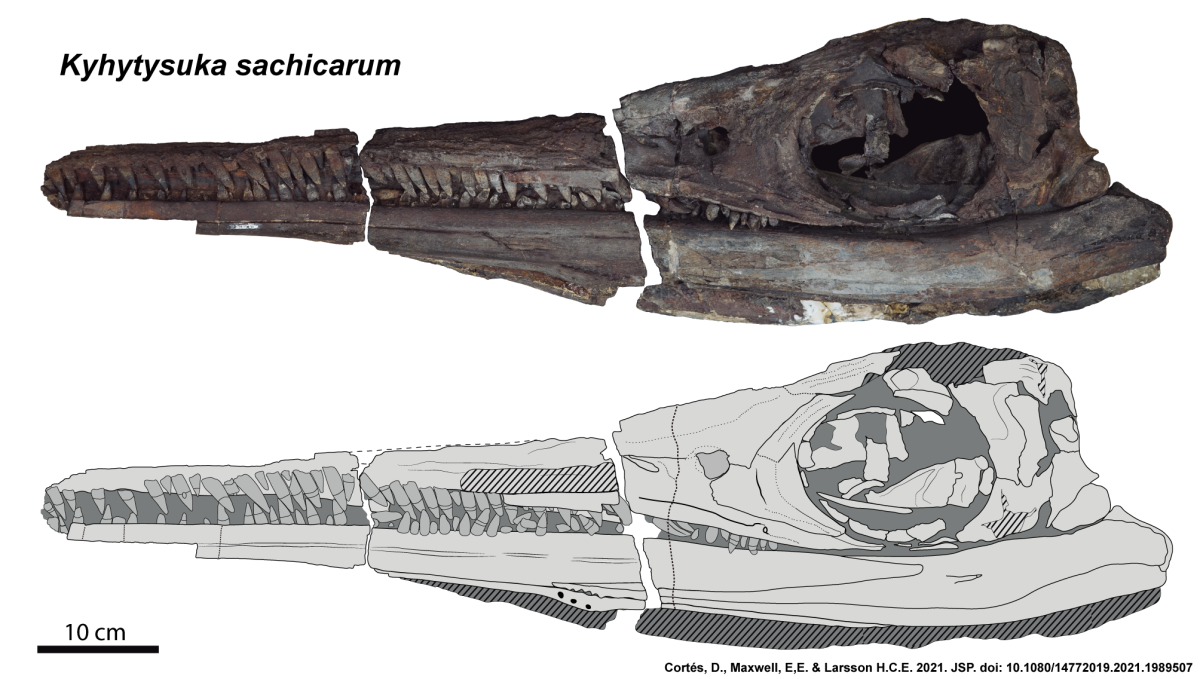

The specimen, a stunningly preserved meter-long skull, is one of the last surviving ichthyosaurs—ancient animals that look eerily like living swordfish.

“This animal evolved a unique dentition that allowed it to eat large prey,” says Hans Larsson, director of the Redpath Museum at McGill University. “Whereas other ichthyosaurs had small, equally sized teeth for feeding on small prey, this new species modified its tooth sizes and spacing to build an arsenal of teeth for dispatching large prey, like big fishes and other marine reptiles.”

“We decided to name it Kyhytysuka which translates to ‘the one that cuts with something sharp’ in an Indigenous language from the region in central Colombia where the fossil was found, to honor the ancient Muisca culture that existed there for millennia,” says Dirley Cortés, a graduate student under the supervision of Larsson and Carlos Jaramillo of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

This new species helps clarify the big picture of ichthyosaur evolution, the researchers say.

“We compared this animal to other Jurassic and Cretaceous ichthyosaurs and were able to define a new type of ichthyosaurs,” says Erin Maxwell of the State Natural History Museum of Stuttgart and a former graduate student of Larsson’s lab.

“This shakes up the evolutionary tree of ichthyosaurs and lets us test new ideas of how they evolved.”

This species comes from an important transitional time during the Early Cretaceous period, the researchers say. At this time, the Earth was coming out of a relatively cool period, had rising sea levels, and the supercontinent Pangea was splitting into northern and southern landmasses. There was also a global extinction event at the end of the Jurassic that changed marine and terrestrial ecosystems.

“Many classic Jurassic marine ecosystems of deep-water feeding ichthyosaurs, short-necked plesiosaurs, and marine-adapted crocodiles were succeeded by new lineages of long-necked plesiosaurs, sea turtles, large marine lizards called mosasaurs, and now this monster ichthyosaur” Cortés says.

“We are discovering many new species in the rocks this new ichthyosaur comes from. We are testing the idea that this region and time in Colombia was an ancient biodiversity hotspot and are using the fossils to better understand the evolution of marine ecosystems during this transitional time,” she adds.

As next steps, the researchers are continuing to explore the wealth of new fossils housed in the Centro de Investigaciones Paleontológicas of Villa de Leyva in Colombia.

“This is where I grew up,” says Cortés, “and it is so rewarding to get to do research here, too.”

The study appears in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

Source: McGill University