A new 3D digital model allows puts the Hunt-Lenox Globe, one of the oldest globes in existence, on view online.

The New York Public Library holds more than 46 million items in its research collections. The Hunt-Lenox Globe is one of the greatest treasures of that vast archive. It’s a tiny, bronze-alloy orb, no bigger than a grapefruit.

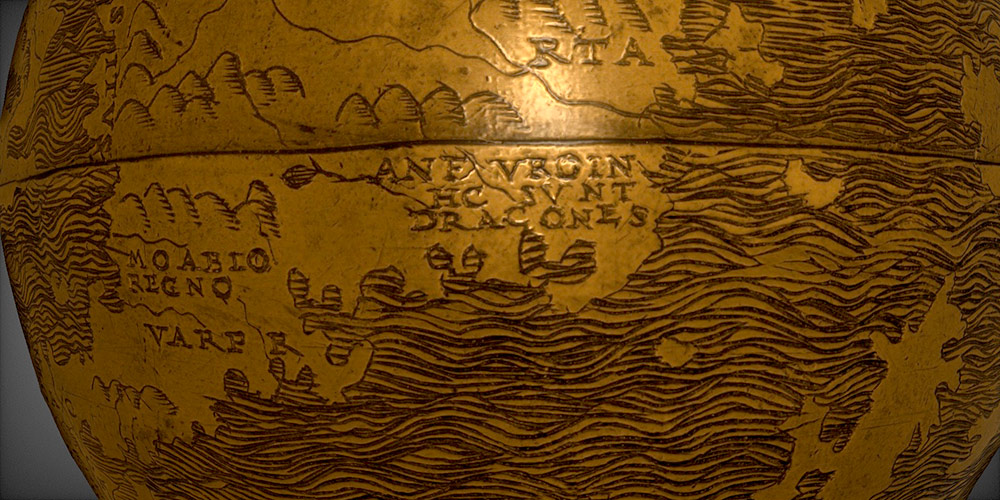

Dating from about 1510, it’s also one of the earliest globes to depict the New World. The model shows the globe in stunning detail, and spinning it lets users see how early cartographers conceived of the world.

Play with the 3D model yourself here.

Revealing the hidden details of the Hunt-Lenox Globe

The Hunt-Lenox Globe’s small size, dark color, and armature—the stand it sits on—conspire to conceal the details of its surface. The land masses etched upon it include two areas representing the New World: one in the location of South America and the other, a mysterious, large island in the southern Indian Ocean.

There are hard-to-spot artistic elements, too: sea monsters, ships, shipwrecks, and, just below the equator, the warning “Hic Sunt Dracones,” or “Here Be Dragons.” Viewers couldn’t see such details even when the New York Public Library placed the globe on exhibit. Given the globe’s value, access for scholars has also been limited.

“It was a perfect storm of circumstances that rendered the object totally inaccessible, even when it was right in front of you,” says Chet Van Duzer, a cartographic historian.

An independent scholar, he’s a member of the board of the Lazarus Project at the University of Rochester, a research group that uses multispectral imaging to recover damaged cultural heritage objects. In collaboration with the New York Public Library, the Lazarus Project, led by director Gregory Heyworth, an associate professor of English and textual science, set out to make the globe accessible to everyone.

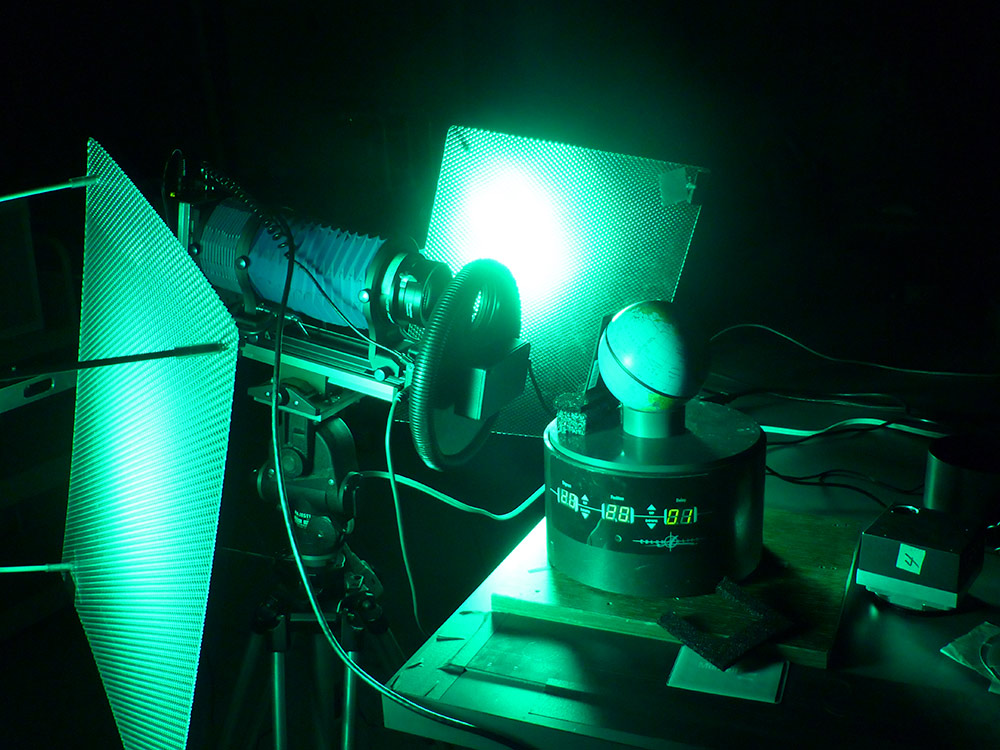

First, the researchers photographed the globe using both conventional photography and multispectral imaging, a process that employs different wavelengths of light to generate highly detailed images.

The team typically uses the process to recover hidden or damaged text or images. Such recovery wasn’t the issue for the Hunt-Lenox, but an eye to the future was: multispectral imaging meticulously records information about an object’s condition, data that allow conservators to monitor the condition of an object over time and adjust its archival storage accordingly.

From the start, the team aimed to produce a 3D model, ultimately collaborating with a software developer in Rochester’s Digital Scholarship Lab. Joshua Romphf builds tools to help with faculty research and the dissemination of findings. To make the Hunt-Lenox Globe model, Romphf expanded on work he and colleagues originally developed to support the Ward Project, a digital repository of zoological and geological materials collected at Rochester in the 19th century, when the three largest museums in the US were at Harvard, the Smithsonian, and the University of Rochester.

Creating the globe model involved two main processes. First was “structure from motion,” a technique that uses overlapping photographic images to create a point cloud—a collection of points in three-dimensional space that represent positions on the surface of the object.

The second process involved reconstructing the surface of the globe, giving it the appearance of texture by laying digital photographs around the model.

“It’s like wrapping a label on a soup can,” says Romphf. “That’s how you get the really detailed features on the globe.”

Getting more eyes on amazing artifacts

The Hunt-Lenox Globe model is an opening salvo for the Lazarus Project’s Resurrect3D, an open-source online educational platform for visualizing, annotating, and displaying difficult-to-study objects. The beta version focuses on damaged cultural heritage objects—manuscripts, globes, maps, and paintings—that have been imaged multispectrally.

The researchers are developing capacities for viewers to experience objects in virtual-, augmented-, and mixed-reality environments as well as a three-dimensional, immersive presentation feature.

“Currently, more than 90% of the objects in museums around the world will never be seen by the public, either for lack of display space or because of damage objects have suffered,” says Heyworth.

He envisions Resurrect3D as a remedy to that invisibility, not only making objects available but also offering a “sensory plenitude that profoundly enhances our ability to understand and learn.”

The team is already at work on its next Resurrect3D project. The Hunt-Lenox has a sibling globe, the Jagiellonian Globe, held by the Jagiellonian University Museum in Poland. The Lazarus Project has imaged this globe, too, and now Romphf is producing a 3D model.

The New York Public Library plans to make the model of the Hunt-Lenox globe accessible on its website.

“It’s an amazing artistic object,” says Van Duzer of the globe, and its depiction of a second America “shows just how difficult it was to map new discoveries and to understand what their relationship was with what people thought they knew about the world.”

And while the Resurrect3D platform is only in the early stages of development, Heyworth is already enthusiastic about its potential to “change how archives work and change the teaching of cultural history.”

Support for the work came from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Source: University of Rochester