The range of colors in the plumage of hummingbirds exceeds the color diversity of all other bird species in total, a new study shows.

Richard Prum has spent years studying the molecules and nanostructures that give many bird species their rich colorful plumage, but nothing prepared him for what he found in hummingbirds.

“We knew that hummingbirds were colorful, but we never imagined that they would rival all the rest of the birds combined,” says Prum, a professor of ornithology of ecology and evolutionary biology at Yale University.

For the study, Gabriela Venable, a former undergraduate student in Prum’s lab, and now a graduate student at Duke University, collected data on the wavelengths of light reflected by feathers of 1,600 samples of plumages from 114 species of hummingbirds.

The researchers then compared this information with an existing dataset of colors found in the plumage of 111 other bird species, from penguins to parrots.

Using their knowledge of avian visual physiology, the researchers were able to describe the diversity of avian plumage colors as seen by the birds themselves, including hues that are not visible to humans.

Birds have four types of color cones that are sensitive to red, green, blue, and ultraviolet/violet colors. So birds can see all the colors visible to humans. But they can also see a host of other colors that humans cannot see, including ultraviolet, and mixtures of ultraviolet with other hues, like ultraviolet-yellow and ultraviolet-green.

These colors are as different from yellow or green as purple is from blue or red. One of the ways that hummingbirds add to avian color diversity is by producing more of these combination colors than other birds.

According to the new findings in Communication Biology, the diversity of bird-visible colors in hummingbird plumages exceeds the known diversity of colors found in the plumages of all other bird species combined, increasing the total of known bird-visible plumage colors by 56%.

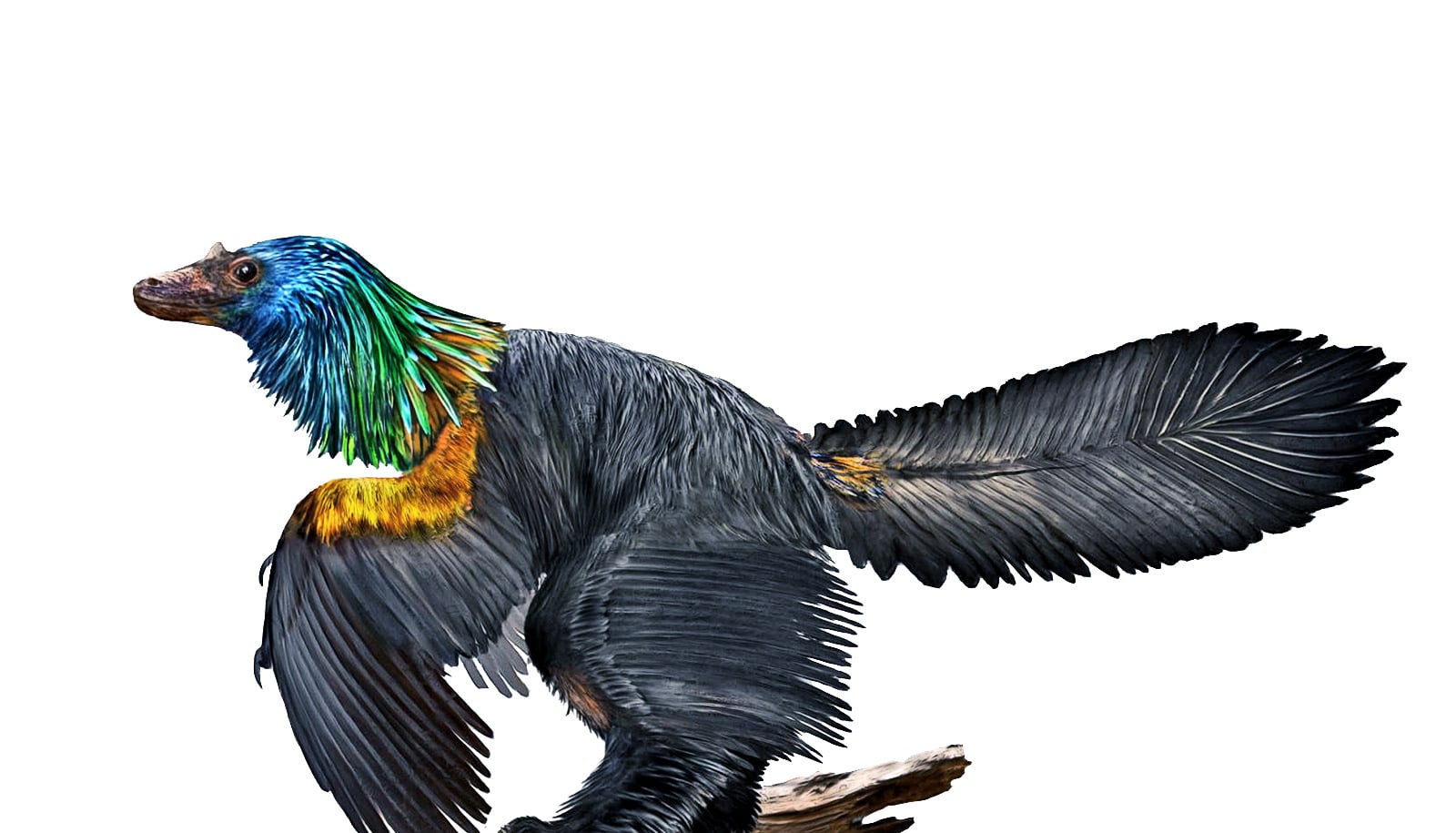

The colors revealed in the hummingbirds’ plumage include saturated blues, blue-greens, and deep purples that are most variable on the animals’ crowns and throats, which they show prominently during mating displays and social interactions.

The sheer breadth of hummingbirds’ colorful plumage is the result of nanostructures in their feather barbules, the smallest filaments that project from their feather barbs.

“Watching a single hummingbird is pretty extraordinary,” Prum says. “But the combination of versatile optical structures and complex sexual displays make hummingbirds the most colorful bird family of all.”

Source: Yale University