Researchers have engineered flying robots that behave like hummingbirds, training them with machine learning algorithms based on various techniques the bird uses naturally every day.

This means that after learning a simulation, the robot “knows” how to move around on its own like a hummingbird would.

The combination of flying like a bird and hovering like an insect could one day offer a better way to maneuver through collapsed buildings and other cluttered spaces to find trapped victims.

Artificial intelligence, combined with flexible flapping wings, also allows the robot to teach itself new tricks. Even though the robot can’t see yet, for example, it can touch surfaces to sense them. Each touch alters an electrical current, which the researchers realized they could track.

“The robot can essentially create a map without seeing its surroundings. This could be helpful in a situation when the robot might be searching for victims in a dark place—and it means one less sensor to add when we do give the robot the ability to see,” says Xinyan Deng, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Purdue University.

Different physics

Engineers can’t make drones infinitely smaller, due to the way conventional aerodynamics work. They wouldn’t be able to generate enough lift to support their weight. But hummingbirds don’t use conventional aerodynamics—and their wings are resilient.

“The physics is simply different; the aerodynamics is inherently unsteady, with high angles of attack and high lift. This makes it possible for smaller, flying animals to exist, and also possible for us to scale down flapping wing robots,” Deng says.

Researchers have been trying for years to decode hummingbird flight so that robots can fly where larger aircraft can’t.

In 2011, DARPA, an agency within the US Department of Defense, commissioned the company AeroVironment to build a robotic hummingbird that was heavier than a real one but not as fast, with helicopter-like flight controls and limited maneuverability. It required a human to be behind a remote control at all times.

12-gram robot

Deng’s group and her collaborators studied hummingbirds for multiple summers in Montana. They documented key hummingbird maneuvers, such as making a rapid 180-degree turn, and translated them to computer algorithms that the robot could learn from when hooked up to a simulation.

Further study on the physics of insects and hummingbirds allowed researchers to build robots smaller than hummingbirds—and even as small as insects—without compromising the way they fly. The smaller the size, the greater the wing flapping frequency, and the more efficiently they fly, Deng says.

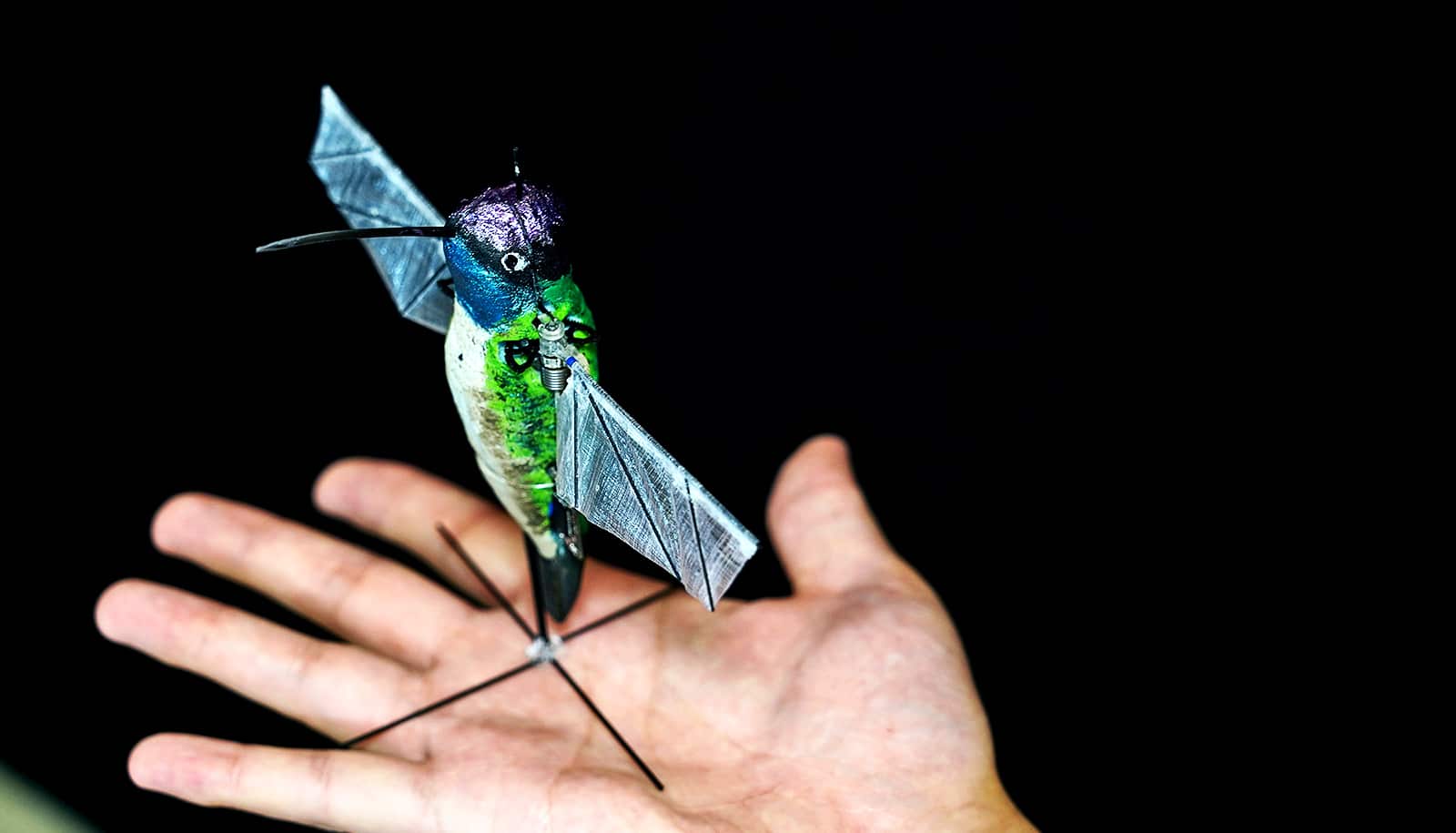

The robots have 3D-printed bodies, wings made of carbon fiber, and laser-cut membranes. The researchers built one hummingbird robot weighing 12 grams—the weight of the average adult magnificent hummingbird—and another insect-sized robot weighing 1 gram. The hummingbird robot can lift more than its own weight, up to 27 grams.

Designing their robots with higher lift gives the researchers more wiggle room to eventually add a battery and sensing technology, such as a camera or GPS. Currently, the robot needs a tether to an energy source while it flies, but that won’t be for much longer, the researchers say.

The robots could fly silently just as a real hummingbird does, making them more ideal for covert operations. And they stay steady through turbulence, which the researchers demonstrated by testing the dynamically scaled wings in an oil tank.

The robot requires only two motors and can control each wing independently of the other, which is how flying animals perform highly agile maneuvers in nature.

“An actual hummingbird has multiple groups of muscles to do power and steering strokes, but a robot should be as light as possible, so that you have maximum performance on minimal weight,” Deng says.

Robotic hummingbirds wouldn’t only help with search-and-rescue missions, but also allow biologists to more reliably study hummingbirds in their natural environment through the senses of a realistic robot.

“We learned from biology to build the robot, and now biological discoveries can happen with extra help from robots,” Deng says.

Simulations of the technology are available open-source. Researchers, including collaborators from the University of Montana, will present the work this month at the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation in Montreal.

Source: Purdue University