New research uses Google search data to better understand who is thinking about human rights, and where those people live.

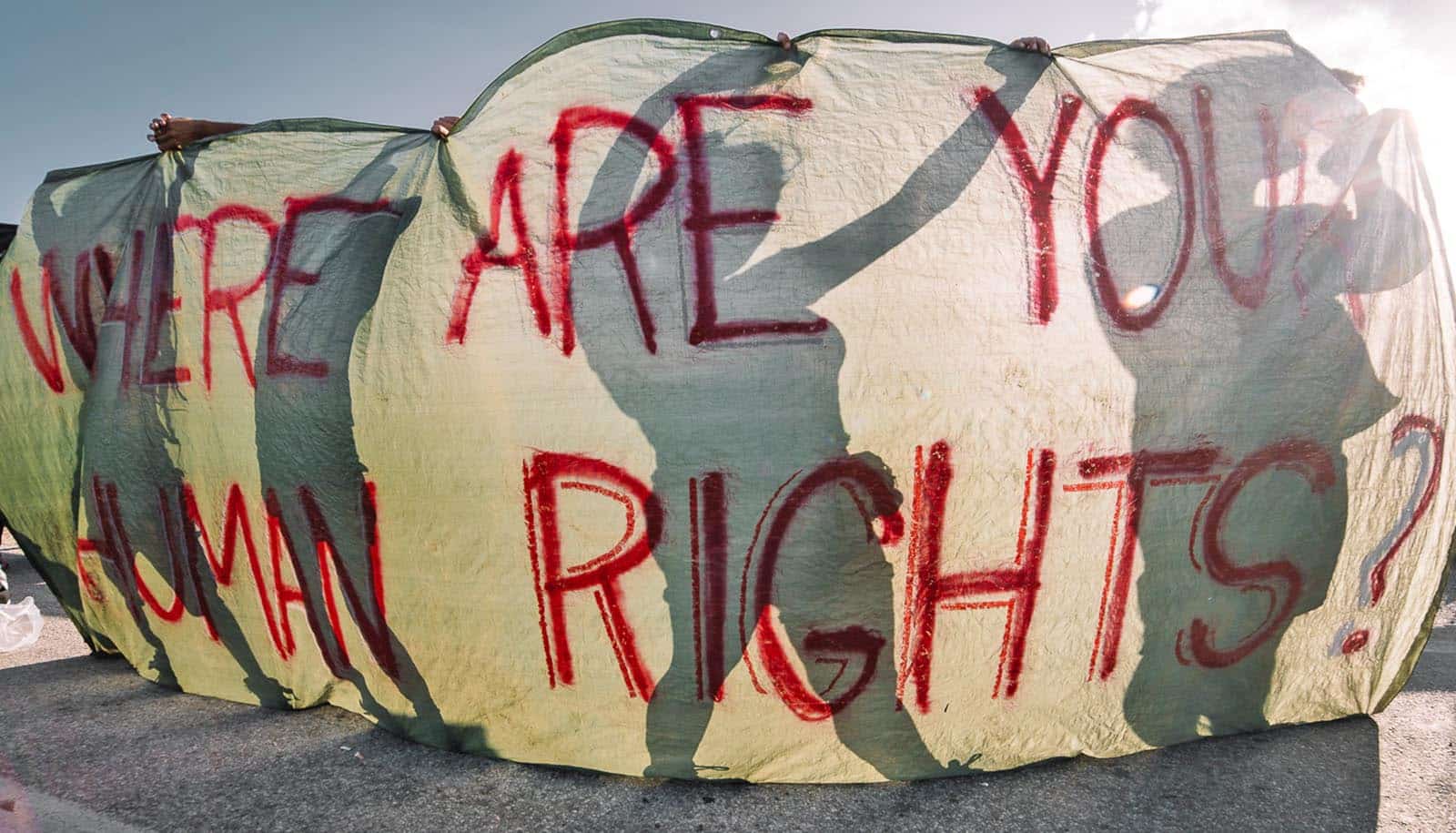

Recently, scholars have expressed doubt that the language of human rights still animates the global fight for better living conditions.

Critics say the “human rights-based approach,” defined by the United Nations as a “conceptual framework for the process of human development that is normatively based on international human rights standards,” is no longer useful for people struggling to bring about change.

But that’s not the story Google tells, according to political scientists Chris Fariss of the University of Michigan and Geoff Dancy of the University of Toronto.

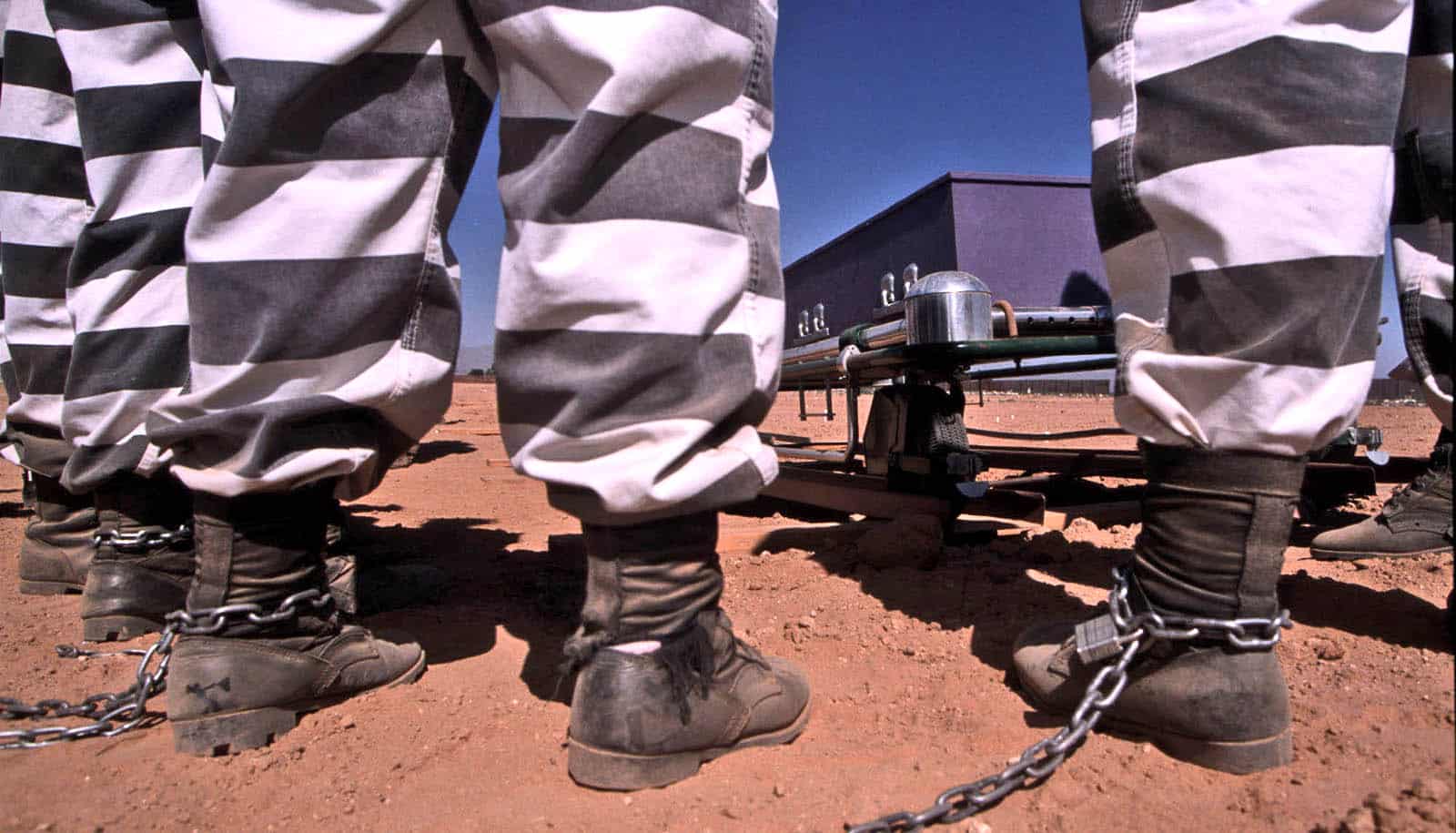

Using Google search data from around the world, the researchers show that human rights are the most popular in the Global South, and that people in countries such as Guatemala and Uganda search the internet for information on human rights far more frequently than people in countries such as the United States or the United Kingdom. Their results appear in the American Political Science Review.

“We think that these findings seriously challenge recent critical work on human rights that says that the discourse no longer resonates among the downtrodden or underprivileged populations in the world,” says Dancy, associate professor of political science. “In fact, it does. People in the Global South still very much want human rights and are very interested in them.”

The researchers say criticism of the human rights framework rests on very little evidence. A few surveys ask questions about human rights, such as the Latin American Public Opinion Project and the World Values Survey. But the information these surveys gather doesn’t capture what people in other countries think about human rights, the researchers say.

“There are a bunch of different arguments about interest in human rights, but all the different arguments make assumptions about the interest and agency of the individual without really evaluating those assumptions empirically,” says Fariss, assistant professor in the University of Michigan department of political science and faculty associate in the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research.

“There’s a little bit of survey data, but it’s not day-to-day, it’s not week-to-week. We can’t really get a good overall global pattern of where this interest is. That’s why we wanted to empirically evaluate this question, and Google Trends has turned into a treasure trove of useful information about what people are searching for.”

The researchers looked at Google Trends, a service that shows aggregated data on search engine queries. They found that, across the globe, the search for the term “human rights” has stayed relatively steady between 2015 and 2019. And because access to the internet is increasing, presumably the search for human rights is stable and likely even increasing, Fariss says.

“There’s more people on the internet, there’s more searching, there’s more engagement with digital devices,” he says. “The total volume of searching is going up and so for the relative rates to stay constant, the relative volume of human rights searching has to be increasing, too.”

Almost universally, the researchers write, human rights interest is most pronounced in countries in the Global South. In English, the three populations who most frequently search “human rights” are in Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Uganda. In Spanish, the top searchers are Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Mexico.

“One claim is that human rights is not as popular as other political concepts,” Fariss says. “But it’s searched as much or more than civil war, terrorism, national security, and ‘right to food.’ It’s searched much more than Amnesty International. And people who are searching for Amnesty International tend to be in the Global North.”

The researchers weren’t able to access data to show the raw total of net Google searchers or the actual number of human rights searches, but they do know the relative rate of these searches. For example, the average Ugandan searches for “human rights” 7.3 times for every time an American does the same. Individuals in Guatemala search 10 times more often than individuals do in Spain.

To validate that these searches for “human rights” occur in places that repress human rights, the researchers compared the search to other equally important concepts, such as malaria. They show that searches for “malaria” were much higher in countries that were experiencing malaria outbreaks.

“We were able to show that by volume, human rights is searched as much or more than a bunch of similarly important concepts like malaria,” Fariss says.

Malaria, he says, is searched at about the same relative rate as human rights.

“People go to Google to try to access information when they need something,” Dancy says. “Just like you might have symptoms of a disease and search for those symptoms on Google and read about it on WebMD, if you’re suffering at the hands of your government, you search for things that are supposed to address that problem on Google.”

While other surveys did not provide expansive data about how people thought about human rights, they did offer proof that people were thinking about human rights at all, the researchers say. They used that survey information to show that people were indeed interested in using the internet to access information about human rights.

In addition, Fariss and Dancy say Google Trends allowed them to get at pretty fine-grained data that might not be captured by larger surveys conducted every few years.

“But those waves are separated by a few years each. We’re able to look at interest and patterns of expressed interest to a scale that just isn’t possible with traditional survey instruments,” Fariss says. “We don’t want to say that this is going to replace surveys, but we think it augments surveys in a really important methodological way.”

Their results also show something pretty significant about the importance of human rights, particularly for those who may need them most.

“Human rights aren’t going anywhere, or at least the language of human rights isn’t going anywhere,” Dancy says. “It’s still the prevailing vocabulary for challenging government violence.”

The researchers’ data is open to any interested scientists or members of the public and is available at Github.

Source: University of Michigan