Historian Stefanos Geroulanos says we need to “take responsibility for what humanity is becoming,” rather than looking to prehistory for easy answers.

Is war our genetic destiny as humans? And how does learning about violence among our ancestors influence our expectations about today?

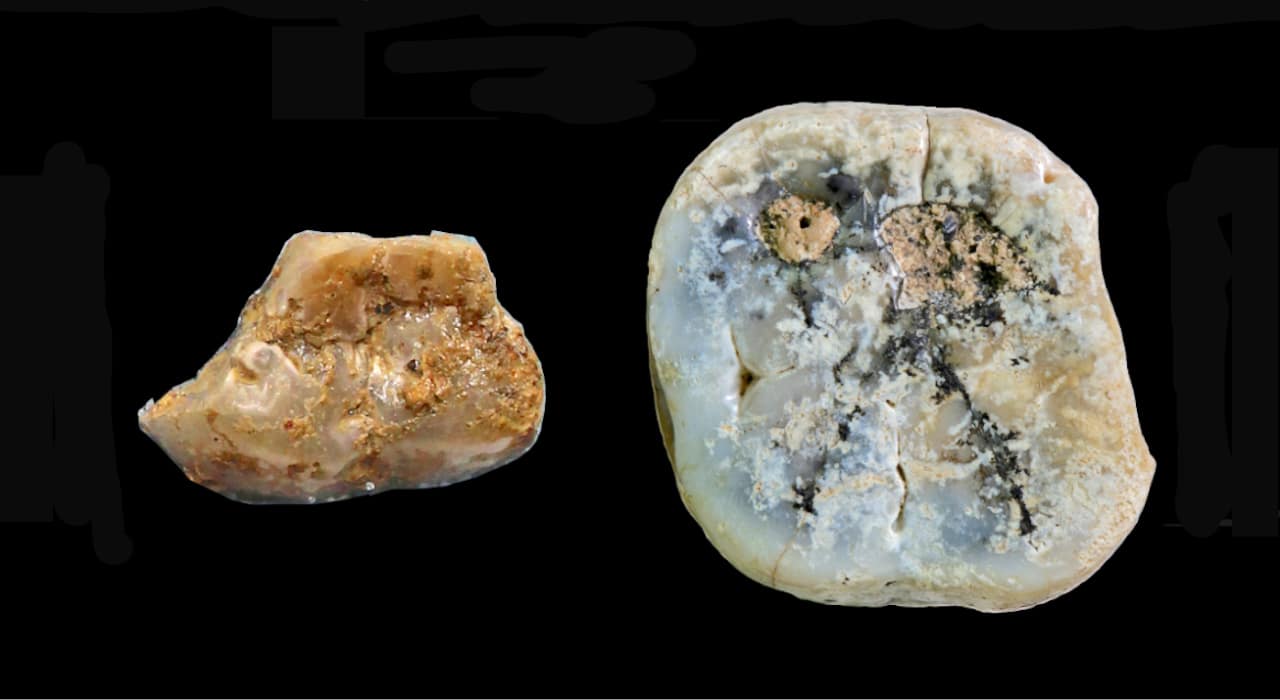

Over the past decade, archaeological discoveries of Homo sapiens and older human relatives from hundreds of thousands of years ago have led to new understandings of early human cultures and those that preceded it.

And for some, the findings—coming at a time when armed conflict is pervasive and inescapable—have raised sobering questions about the nature of humanity itself.

“War may be a long-standing mainstay of human life, an inheritance from our deepest past,” Ross Andersen of the Atlantic wrote in November, 2023. “But each generation gets to decide whether to keep passing it down.”

But New York University historian Geroulanos, author of The Invention of Prehistory: Empire, Violence, and Our Obsession with Human Origins (WW Norton, 2024), offers a strong challenge to that perspective.

“War today has nothing to do with human origins and has nothing to do with war a century ago,” he says. “What we would refer to as war today involves drones, involves extraordinary capacity to level city blocks, involves attacks on the computer networks of enemies, and it involves the threat of nuclear destruction.”

“We may find archeological answers to some of these questions, but they’ll be completely immaterial to what war is today,” adds Geroulanos. “So if we had begun with the idea that we will solve the problem of war by way of these questions, we are misunderstanding the problem to begin with.”

Geroulanos’s research is not on illuminating human nature prior to written records but, rather on analyzing how others have sought to understand humanity through excavations of “prehistory.”

“I do not write to cast aspersions on particular researchers, their good will, or their ability,” he writes in the new book. “Nor is scientific inquiry my target here. I am much more interested in how these concepts shaped modern humanity.”

Here, Geroulanos, director of NYU’s Remarque Institute, explains historical inquiries into humanity’s past, the contradictions these pursuits reveal, and how they influence 21st century life:

You suggest that “every story about humanity is a tale of grandeur and dehumanization.” What do you mean by this?

Religious accounts of human origins—the Bible, most significantly—were much more about the glory of God than about an explanation of human character and behavior. The science of human origins hasn’t been simply about displacing religious accounts to offer scientific ones. It is really about explaining how, given the immense complexity of nature, from the Big Bang through evolution all the way to today, humans came to be conscious of themselves and, in a way, to see themselves as the most complex beings that we are aware of—the top of the great chain of being.

Of course, if that’s a story of achievement, which is how it’s usually told, it is also a story that’s had its victims. The study of human origins isn’t really about some old skulls or about some cave art. It is about the grandeur of those who made it, as opposed to the grandeur of those who didn’t. It’s about those who were found, those who went extinct, and those who have been deemed not civilized enough to survive. And the stories of the 19th and 20th centuries are very much about that distinction.

You write that the “humanity we wish for,” in part, depends on “our eagerness to deceive each other and ourselves.” Are you suggesting that what researchers hope may be true about humanity shapes the kinds of discoveries they make?

One thing that I learned while writing this book is that people who study human origins are not bad scientists, but they all have an ideal of humanity. They have a humanity that they wish for. And in a way, the politics of that humanity plays into their work.

This is a problem because a certain figure of an ideal humanity seeps into ideas that have virtually nothing to do with it. And so it becomes easy for someone to think that the humanity that they’re trying to understand is all good—that their ideals are pure and clean. And as we know, there’s great danger in this belief in ideals. That’s not simply a way of deceiving others. It’s also about deceiving ourselves.

Deception signals something intentional. But it seems part of what you describe suggests being naive.

I think that there is a way in which a certain kind of deception is part and parcel of this understanding of humanity—that every ideal involves a simplification. And in that gesture of simplification, there absolutely is a gesture of deception. It’s an argument that those who belong within that humanity—however open and large it’s supposed to be—couldn’t possibly be doing something wrong.

The great version of this, which I track in the book, has to do with a passage from Darwin in The Descent of Man. That passage says that as humans advance in civilization, they extend their sympathies to the rest of humanity. But by the same formulation that Darwin uses, which different generations have used since him, those who do not extend their sympathies to humanity the way that he understands it are not part of civilization.

This same passage has been used to attack those seen as warmongering Indigenous people or as barbarians or as savages. It’s been used to suggest that some people deserve protection and others don’t.

Now, I don’t necessarily think that Darwin and others were actively working to deceive their contemporaries. But I certainly think that they created a way to deceive themselves.

You note that the Nazi Party saw the Aryan race as both “true creators of culture” and as “barbarians.” How did those seemingly contradictory views contribute to its horrific agenda?

There were many different trends within the Nazi Party, from the modernizers to those who were obsessed with a certain vision of the German “Volk” as very traditional. Multiple ideas about human prehistory were being invoked at the same time.

So the Germans could imagine themselves as the inheritors of the ancient Germanic so-called barbarians who destroyed Rome. And they could imagine themselves as some sort of primordial creators of culture at the same time. Because they opposed what they understood as a Jewish cosmopolitan, nonracial thinking, they didn’t have to reconcile the different expressions that they used. They did, in fact, use many opposite arguments at the same time.

To use just the two examples that you brought in, they could claim, “We appear to be barbarians from the perspective of the fallen civilization in which we live. And that’s because we are true creators of culture.” That was indeed Hitler’s attitude. In many respects, that wasn’t what enabled their racism and antisemitism—but it played a role in their racism and antisemitism and in their gradual sense that they and only they could maintain the conscience of the race and the power of the race itself. So in that regard, the problem with what they saw as a “Jewish civilization” and what they wanted to destroy and eliminate as a “Jewish civilization” had everything to do with restoring a kind of Aryan paradise.

You observe that much anti-immigrant rhetoric—conveyed through the “Great Replacement” theory advanced by white supremacists today—is linked to notions of “prehistory.” How so?

There are multiple episodes that matter a great deal in this consideration. One has to do with the story of “Out of Africa”—the idea of our African origins as human beings as a geographical story. But we generally ignore the way in which it’s been used politically since it was proposed in the 1950s. Politically, it was used to mark a distinction between Black Africans and the apartheid regime in South Africa. Specifically, it was used by the apartheid regime and by its supporters to speak of a difference between so-called “killer apes” and modern civilization. That same language has been used in Europe as well.

Today, the far right’s anti-immigrant rhetoric uses intimations—dog whistles, as we call them—that speak to people’s anxieties. They speak to their sense of how they belong. They speak to a certain emotional connection. And in producing this language of “savages,” of “killer apes,” of “invading foreigners,” and so on, there’s very little distance from one expression to the other. On the one hand, we can sit on the side and say, “The far right just is obsessed with any language that it can find.” But we can also turn around and see how the far right uses a series of anxieties and emotions in order to play on this language and to produce the sense of an enemy.

In considering armed conflict, you distill two opposing scholarly points of view: “War is the opposite of civilization” and “War is civilization.” How would settling that debate about humanity’s ancient past help us today?

First of all, we should ask: “Is it possible to answer between these?” I think the answer is, “There is no answer that’ll prove satisfactory.” It’s just impossible to solve because these positions rely on how we understand ourselves today rather than on what happened in human prehistory.

Now, how would it be beneficial, nevertheless, to get an answer? I think the advocates of both positions would ultimately like an end to war, and they would like a conception of humanity in which it becomes possible to have a more equitable society—a society less invested in violence. So even though I don’t think an answer is achievable, it’s as though almost any answer appears beneficial.

But I think there is a broader issue which has to do with us understanding that as human beings today we aren’t some sort of pure creature—we have transformed so dramatically in the last 40 or 50 years, and perhaps even faster in the last 20. And that we need to take responsibility for what that humanity is becoming.

What Homo sapiens were for 50,000 or 100,000 or 200,000 years is very, very different from what Homo sapiens have been for the last 5,000—and it’s certainly very different from what life is like today. We have transformed and warped both humanity on this planet so dramatically that these ideas of a long history are really troubling. Yet we are committed to them, and it’s so hard to look outside of them. But in reality, our bodies, our economic systems, our social relations, our family relations, and our politics have very little to do with this longer history and a great deal to do with the much shorter one.

During the Spanish Civil War, philosopher Walter Benjamin wrote that “there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” Have our understandings of “civilization” and “barbarism” changed since then?

The relevant problem, all the way through the end of the 20th century and into the 21st, has really been that any organized state that goes to war describes its enemies as barbarians. Such was the case with Afghanistan and such was the case with Iraq. It feels as though this hasn’t changed very much. The distinction between the civilized and the supposed barbarians is absolutely still here. And that is an ideology that helps those who present themselves as civilized to escape a certain criticism or a certain kind of examination: What is it that’s acceptable violence and what’s not acceptable violence?

We all would like to think that we know what the limits of acceptable violence are, but in reality, we’re tolerant with certain practices that are utterly barbaric when our states or friends are carrying them out. Benjamin was thinking about bombing, and bombing to this day is an utterly horrific practice whose practitioners proclaim themselves civilized and their enemies as barbarians. Unfortunately, that hasn’t changed.

Source: NYU