Human papillomavirus infection rates are increasing in women born after 1980 who did not receive the HPV vaccine, research finds.

And this puts them at higher risk for HPV-related cancers, according to the new study.

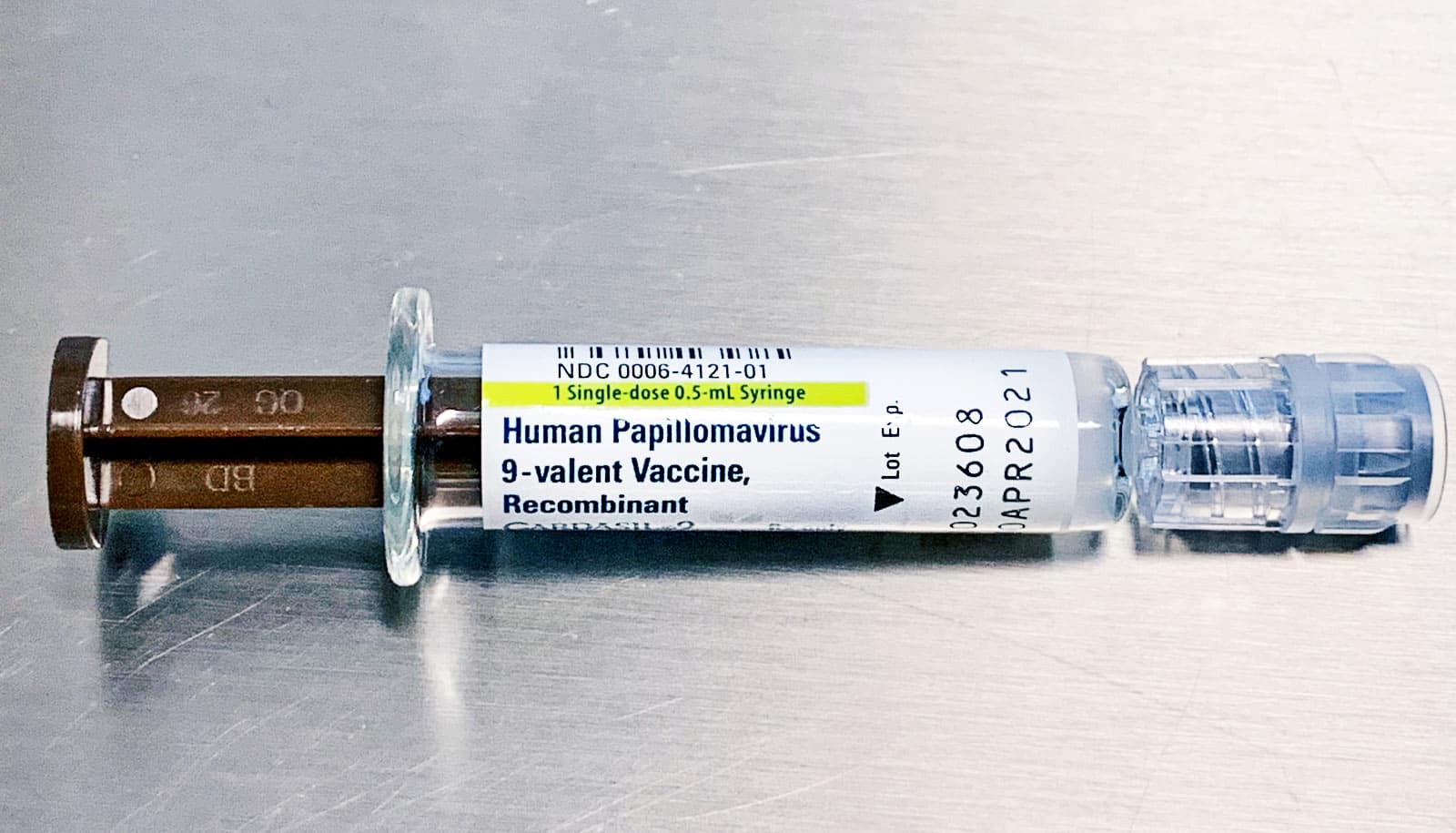

While more than 90 percent of HPV-related cancers are preventable, HPV causes more than 40,000 cases of cancer in the United States each year, including cervical, oropharyngeal, anal, and other genital cancers. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that at least half of all sexually active men and women will acquire HPV in their lifetime.

“If we know which groups of people have the highest rates of HPV, we can do a better job of preventing cancer through vaccination and screening,” says lead author Andrew Brouwer, a researcher at the University of Michigan School of Public Health.

Because testing for genital HPV started in 2003 for women and in 2013 for men, there are no direct measurements of how HPV incidence and prevalence have changed over the past decades—before the vaccine became available for women in 2006 and for men in 2009.

Brouwer says previous analyses focused only on measures of current HPV infection (viral DNA) or past HPV infection (antibodies), producing sometimes competing results, making it difficult for experts to predict current and future trends.

For their analysis, Brouwer and colleagues developed a model that uses both HPV infection and past infection data, as well as mathematical representations of the underlying mechanisms of infection, recovery, and the generation of antibodies, to paint a better picture of HPV prevalence in the present and past.

Their model indicates that while there may be a substantial increase in HPV prevalence in more recent birth cohorts, HPV vaccination may ultimately control adverse HPV-related outcomes, including genital warts and cancer. Questions still remain, such as why there is a peak in HPV infection among 45-to-55-year-olds.

“Did everyone in this cohort have higher HPV throughout their lifetimes? Or is it more a function of biological or behavior changes when people reach this age?” Brouwer says.

Brouwer says his group will now try to understand how HPV is transmitted between genital, oral, and anal sites, and plan to study multisite HPV infections in young people.

The new findings appear in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Source: University of Michigan