Hispanic patients who are hospitalized with respiratory failure are five times more likely than non-Hispanic patients to receive deep sedation while on a ventilator, according to a new study.

The study is the first to identify what may be driving worse outcomes for Hispanic patients who are critically ill with respiratory failure.

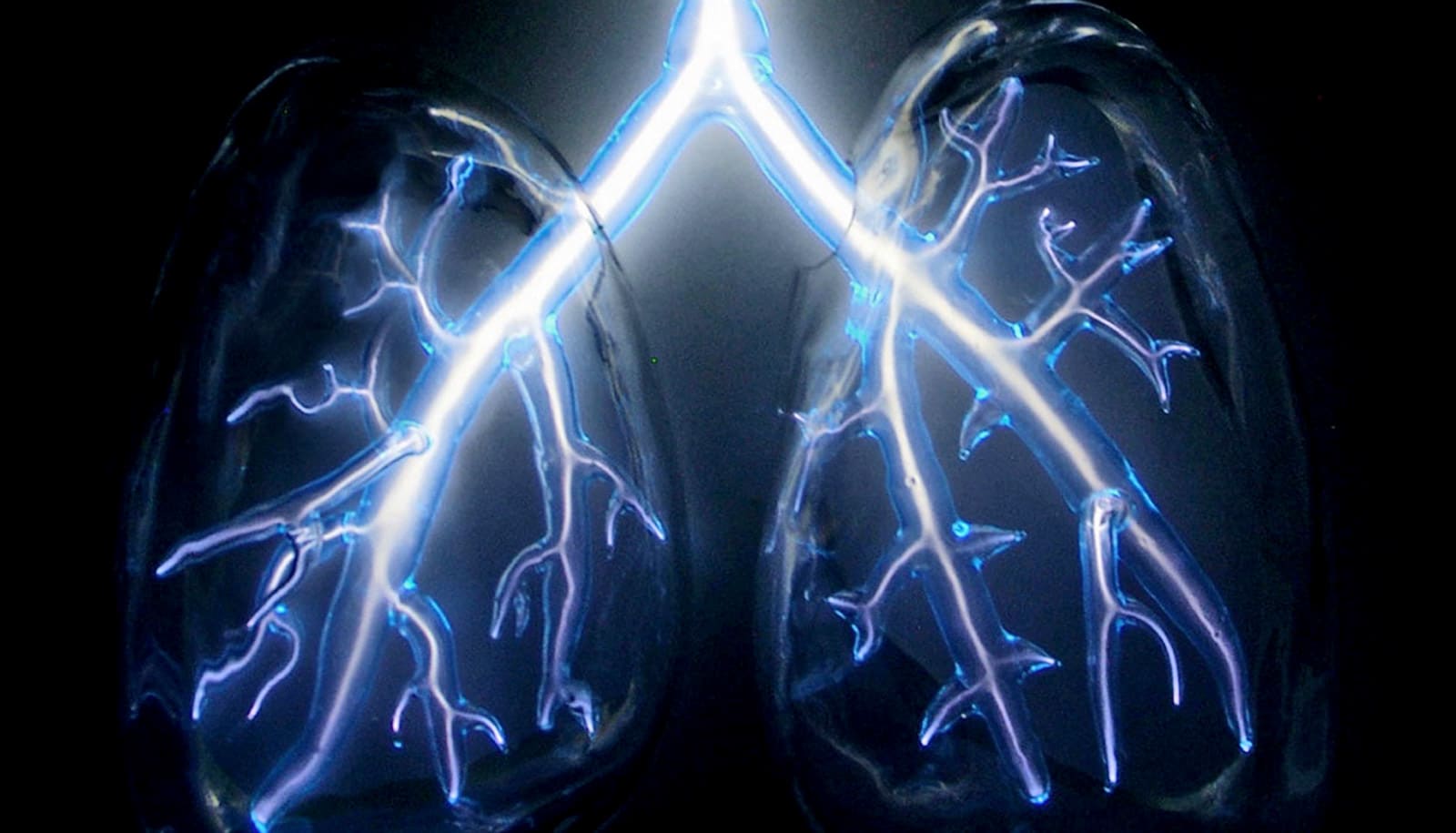

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening lung condition in which fluid builds up inside the lungs, leading to difficulty breathing and low blood oxygen levels. This form of respiratory failure can result from infections such as COVID-19 or sepsis, or can be caused by injuries, nearly drowning, or inhaling harmful substances.

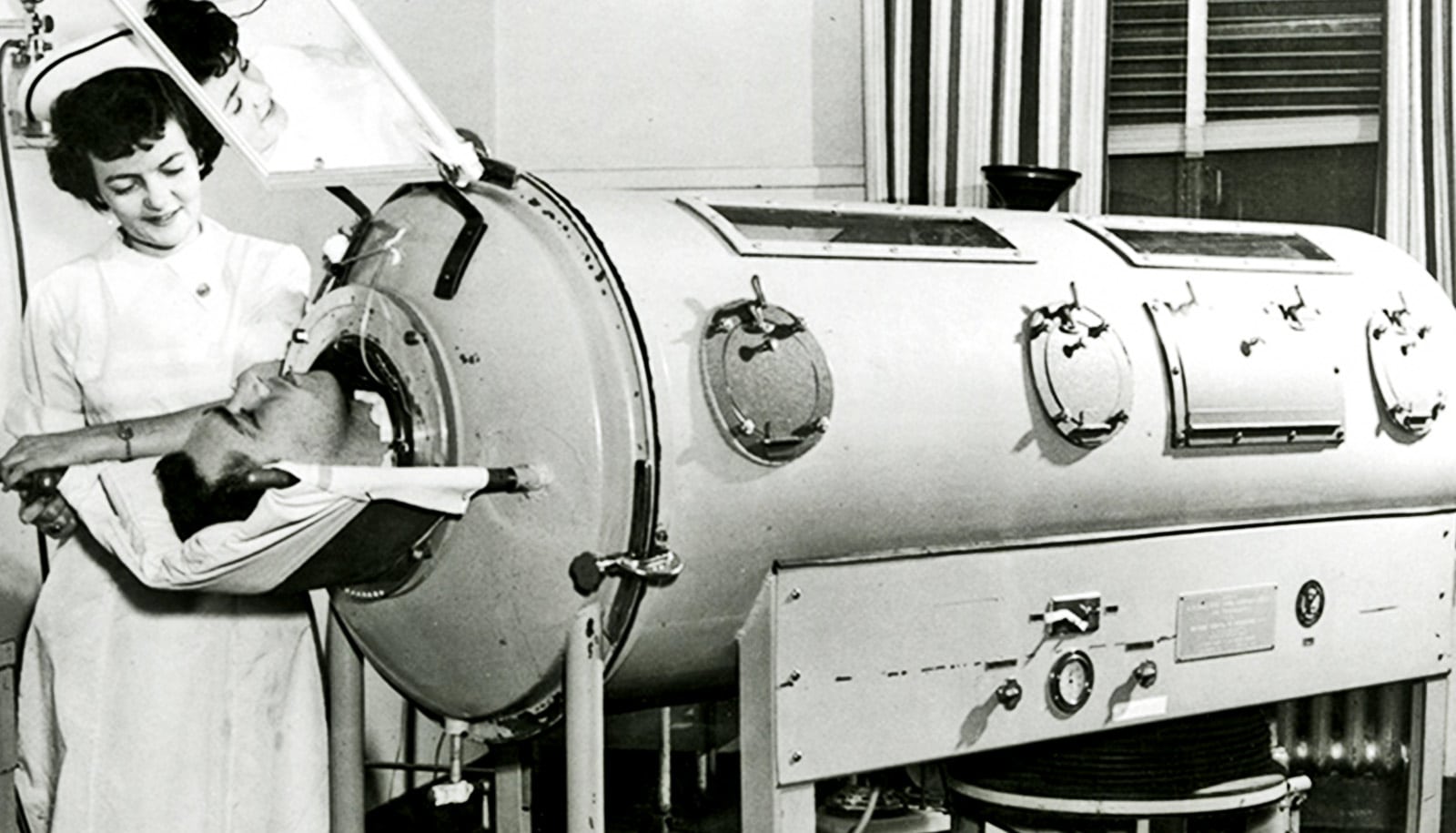

Patients with serious cases of ARDS are admitted to the intensive care unit, where they are often sedated and put on a mechanical ventilator to help them breathe. While sedation can keep ventilated patients comfortable and calm, higher levels of anesthesia—especially soon after a patient is connected to a ventilator—are linked to worse outcomes, including delirium and death.

As a result, clinical practice guidelines recommend that patients are lightly sedated.

While ARDS is deadly for many patients, researchers have found troubling disparities in outcomes for respiratory failure.

“We’ve known for more than a decade that Hispanic individuals are more likely to die when they experience respiratory failure compared to non-Hispanic individuals. Until now, we haven’t known why that might be,” says Mari Armstrong-Hough, assistant professor in the departments of social and behavioral sciences and epidemiology at the New York University School of Global Public Health and the study’s co-principal investigator.

“Is it because of the quality of the hospitals that serve many Hispanic patients, or individual factors related to their health or the care they receive?”

Armstrong-Hough and her colleagues at NYU and the University of Michigan analyzed data from a clinical trial in 48 US hospitals that included 505 patients with moderate to severe ARDS who were randomized to receive the standard care for ARDS. The patients were ventilated and light sedation was recommended.

When the researchers analyzed the levels of sedation that patients actually received, they found that more than 90% of patients were deeply sedated at some point over the first five days on a ventilator, and patients spent nearly 75% of these days deeply sedated.

Notably, levels of sedation were particularly high for Hispanic patients. After accounting for a range of demographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics, Hispanic patients were five times more likely to be deeply sedated while on a ventilator compared to non-Hispanic white patients.

“Our study shows that Hispanic patients spend more time deeply sedated than non-Hispanic patients. Deep sedation is a known risk factor for death as well as a host of other major long-term problems,” says Armstrong-Hough.

“This is an especially important finding because oversedation is modifiable—in other words, we can do something about it.”

While the authors cite a need for more research to explain why Hispanic patients are more likely to be deeply sedated, they note several factors that could contribute to this disparity, including language barriers and cultural differences between patients and clinicians, implicit bias in clinical decision making, and quality differences among hospitals serving Hispanic patients.

“There is a need to broadly assess how care is delivered to Hispanic patients, examine why differences in care exist, and develop interventions that provide resources to ICUs to eliminate disparities that may result in worse outcomes,” says Thomas Valley, associate professor in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan and the study’s co-principal investigator.

“Given the widespread use of deep sedation we found in the study, this is an opportunity to improve sedation for everyone, but there is clearly a greater need to improve sedation for Hispanic patients because of what we know about disparities in their outcomes.”

The study is published in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society. Additional coauthors are from NYU, the University of Michigan, Johns Hopkins University, and Oregon Health & Science University.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the American Thoracic Society/CHEST Foundation supported the work.

Source: NYU