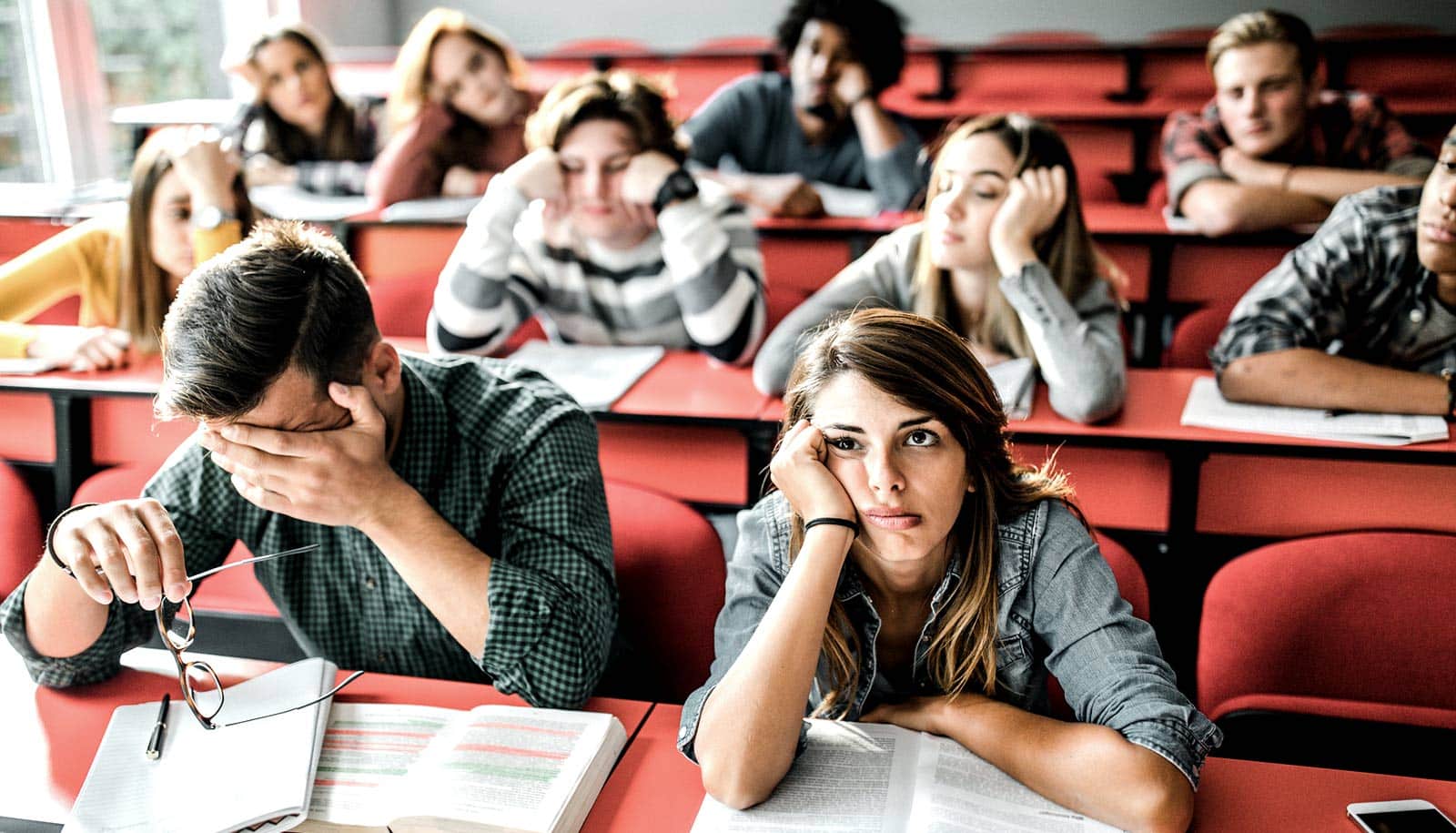

Ask a high school student how he or she typically feels at school, and you’ll likely hear one of three answers: tired, bored, or stressed.

For a new study, researchers surveyed 21,678 US high school students and found that nearly 75% of the students’ self-reported feelings related to school were negative.

The study included a second, “experience sampling” study in which 472 high school students in Connecticut reported their feelings at distinct moments throughout the school day. These momentary assessments told the same story: High school students report negative feelings 60% of the time.

“It was higher than we expected,” says coauthor Zorana Ivcevic, a research scientist at the Yale University Center for Emotional Intelligence and the Yale Child Study Center. “We know from talking to students that they are feeling tired, stressed, and bored, but were surprised by how overwhelming it was.”

Researchers recruited the students for the survey through email lists of partner schools and through social media channels from nonprofits like the Greater Good Science Center and Born this Way Foundation.

The students represent urban, suburban, and rural school districts across all 50 states and both public and private schools. All demographic groups reported mostly negative feelings about school, but girls were slightly more negative than boys, the researchers found.

“Overall,” says coauthor Marc Brackett, founding director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence and a professor in the Child Study Center, “students see school as a place where they experience negative emotions.”

Bored and tired go hand-in-hand

The first online survey asked students to “think about the range of positive and negative feelings you have in school” and provide answers in three open text boxes. The survey also asked them to rate on a scale of 0 (never) to 100 (always) how often they felt several different emotions: happy, proud, cheerful, joyful, lively, sad, mad, miserable, afraid, scared, stressed, and bored.

In the open-ended responses, students most commonly reported feeling tired (58%). The next most-reported emotions—all just under 50%—were stressed, bored, calm, and happy. The ratings scale supported the findings, with students reporting feeling stressed (79.83%) and bored (69.51%) the most.

When researchers examined those feelings with more granularity, they revealed something interesting. The most-cited positive descriptions—calm and happy—are vague, Ivcevic says.

“They are on the positive side of zero,” Ivcevic says, “but they are not energized or enthusiastic.” Feeling “interested” or “curious,” she notes, would reveal a high level of engagement predictive of deeper and more enduring learning.

Many of the negative feelings may interrelate, with tiredness, for example, contributing to boredom or stress, she says. “Boredom is in many ways similar to being tired. It’s a feeling of being drained, low-energy. Physical states, such as being tired, can be at times misattributed as emotional states, such as boredom.”

Is later high school the answer?

The researchers note that the way students feel at school has important implications in their performance and their overall health and well-being.

“Students spend a lot of their waking time at school,” Ivcevic says. “Kids are at school to learn, and emotions have a substantial impact on their attention. If you’re bored, do you hear what’s being said around you?”

Public attention has turned recently to early start times for high schools in the US and how that contributes to sleep deprivation among students, which associates with a number of other health risks—including weight gain, depression, and drug use—and poor academic performance.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that high schools start at 8:30 AM or later, but the vast majority start earlier.

“It is possible that being tired is making school more taxing,” Ivcevic says, “so that it is more difficult for students to show curiosity and interest. It is like having an extra weight to carry.”

Unfortunately, decisions about school start times are often not made with students’ health and well-being in mind, she says.

“There has been a movement in recent years to move school start times later. The reasons for not moving it have nothing to do with students’ wellbeing or their ability to learn.” Instead, she says, concerns about athletic programs, extracurricular activities, and transportation often drive the decisions.

The paper appears in the Journal of Learning and Instruction.

Source: Brita Belli for Yale University