A new white paint can keep surfaces up to 18 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than their ambient surroundings, researchers report.

The paint would absorb nearly no solar energy and send heat away from the building, replacing the need for air conditioning, according to the researchers. Without the building heating up, air conditioning wouldn’t have to kick on.

“It’s very counterintuitive for a surface in direct sunlight to be cooler than the temperature your local weather station reports for that area, but we’ve shown this to be possible,” says Xiulin Ruan, a professor of mechanical engineering at Purdue University.

The paint would not only send heat away from a surface, but also away from Earth into deep space where heat travels indefinitely at the speed of light. This way, heat doesn’t get trapped within the atmosphere and contribute to global warming.

“We’re not moving heat from the surface to the atmosphere. We’re just dumping it all out into the universe, which is an infinite heat sink,” says Xiangyu Li, a postdoctoral researcher at Massachusetts Institute of Technology who worked on this project as a PhD student in Ruan’s lab.

Earth’s surface would actually get cooler with this technology if the paint were applied to a variety of surfaces including roads, rooftops, and cars all over the world, the researchers say.

The paint reflects 95.5% sunlight

As reported in Cell Reports Physical Science, when compared with commercial white paint, the new paint can maintain a lower temperature under direct sunlight and reflect more ultraviolet rays.

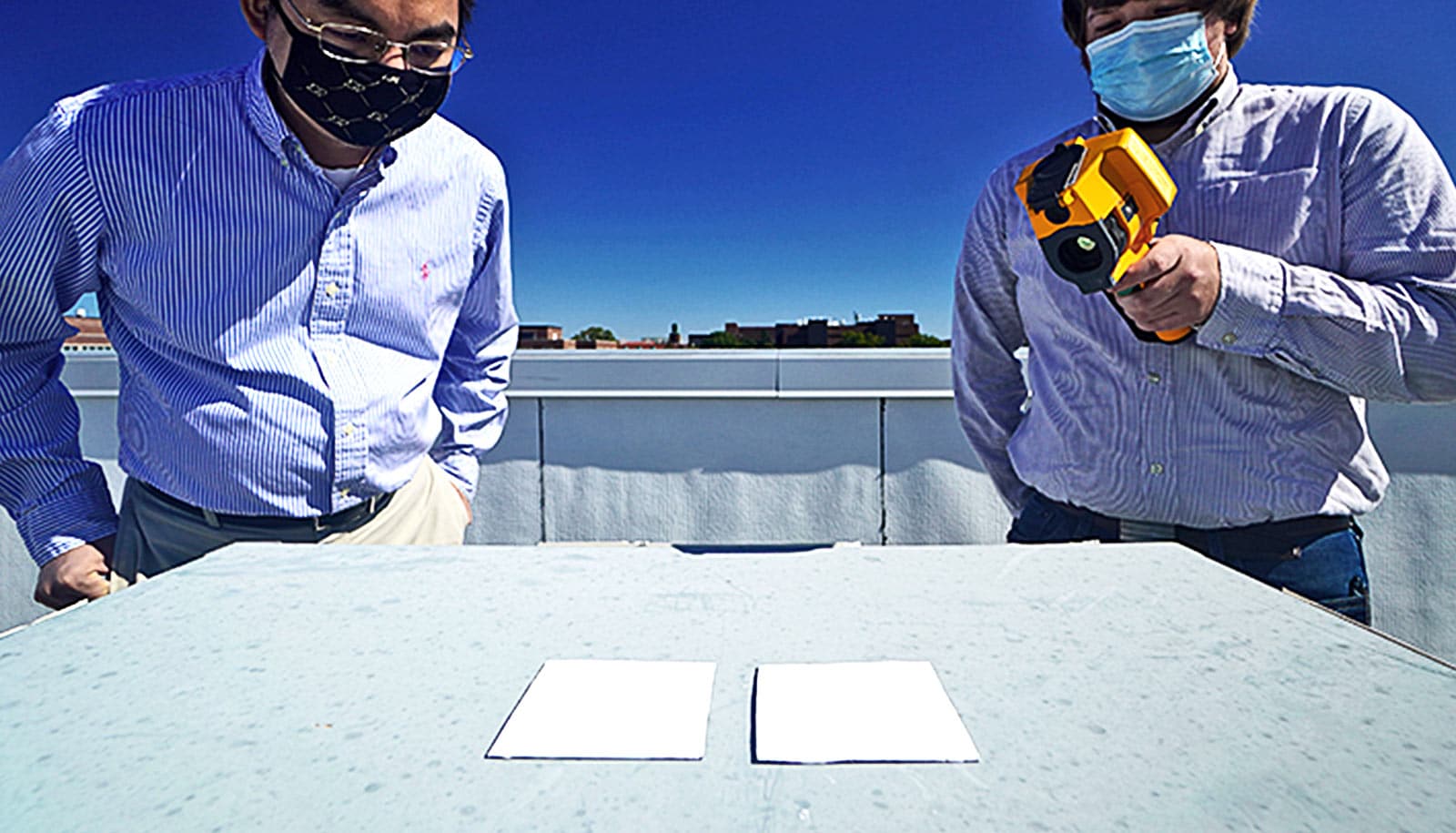

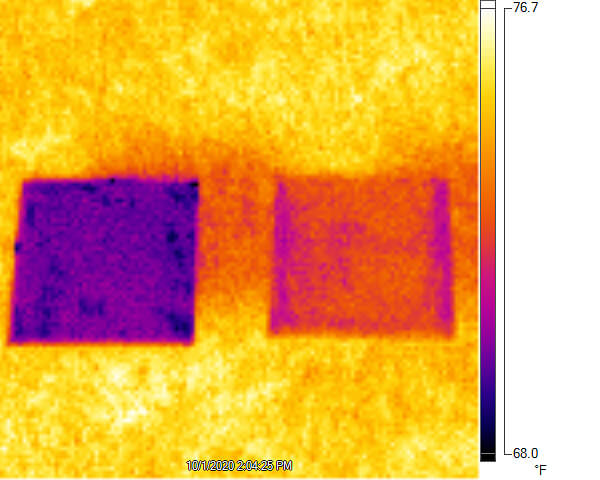

Their proof is infrared camera images they took of the two paints in rooftop experiments.

“An infrared camera gives you a temperature reading just like a thermometer would to judge if someone has a fever. These readings confirmed that our paint has a lower temperature than both its surroundings and the commercial counterpart,” Ruan says.

Commercial “heat rejecting paints” currently on the market reflect only 80%-90% of sunlight and cannot achieve temperatures below their surroundings. The new white paint reflects 95.5% sunlight and efficiently radiates infrared heat.

Developing the paint formulation wasn’t easy. The six-year study builds on attempts going back to the 1970s to develop radiative cooling paint as a feasible alternative to traditional air conditioners.

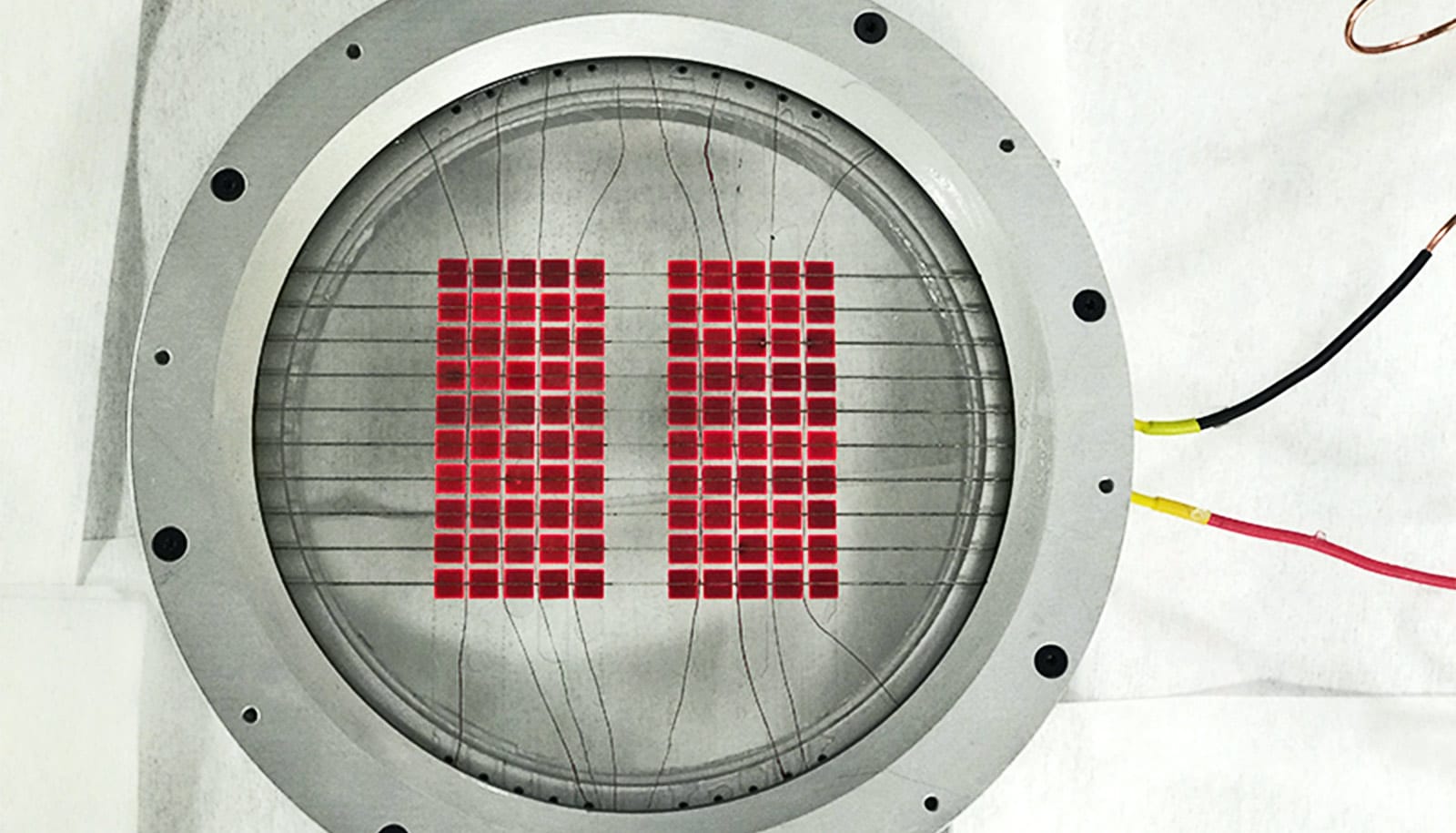

The researchers considered over 100 different material combinations, narrowed them down to 10, and tested about 50 different formulations for each material. They landed on a formulation made of calcium carbonate, an Earth-abundant compound commonly found in rocks and seashells.

This compound, used as the paint’s filler, allowed the formulation to behave essentially the same as commercial white paint but with greatly enhanced cooling properties. These calcium carbonate fillers absorb almost no ultraviolet rays due to a so-called large “band gap,” a result of their atomic structure. They also have a high concentration of particles that are different sizes, allowing the paint to scatter a wider range of wavelengths.

‘Free air conditioning’

According to the researchers’ cost estimates, this paint would be both cheaper to produce than its commercial alternative and could save about a dollar per day that would have been spent on air conditioning for a one-story house of approximately 1,076 square feet.

“Your air conditioning kicks on mainly due to sunlight heating up the roof and walls and making the inside of your house feel warmer. This paint is basically creating free air conditioning by reflecting that sunlight and offsetting those heat gains from inside your house,” says coauthor Joseph Peoples, a PhD student in mechanical engineering.

Cutting down on air conditioning also means using less energy from coal, which could lead to reduced carbon dioxide emissions, Peoples says. The researchers have further studies underway to evaluate these benefits.

The researchers are working on developing other paint colors that could have cooling benefits. The team filed an international patent application on this paint formulation through the Purdue Research Foundation Office of Technology Commercialization.

The Cooling Technologies Research Center at Purdue University and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research through the Defense University Research Instrumentation Program funded the work.

Source: Purdue University