Researchers have created a minimally invasive platform that can deliver a nanomaterial that turns the body’s inflammatory response into a signal to heal rather than a means of scarring following a heart attack.

For people who survive a heart attack, the days immediately following the event are critical for their longevity and long-term healing of the heart’s tissue.

Tissue engineering strategies to replace or supplement the extracellular matrix that degrades following a heart attack are not new, but minimally invasive catheter delivery doesn’t work for most promising hydrogels because they clog the tube. The researchers demonstrated a novel way to deliver a bioactivated, biodegradable, regenerative substance through a noninvasive catheter without clogging.

The research, which they conducted in vivo in a rat model, appears in the journal Nature Communications.

“This research centered on building a dynamic platform, and the beauty is that this delivery system now can be modified to use different chemistries or therapeutics,” says Nathan C. Gianneschi, a professor in the chemistry department and in the materials science and engineering and biomedical engineering departments in the McCormick School of Engineering at Northwestern University.

Heart healing

When a person has a heart attack, the extracellular matrix is stripped away and scar tissue forms in its place, decreasing the heart’s functionality. Because of this, most heart attack survivors have some degree of heart disease, the leading cause of death in America.

“We sought to create a peptide-based approach because the compounds form nanofibers that look and mechanically act very similar to native extracellular matrix. The compounds also are biodegradable and biocompatible,” says first author Andrea Carlini, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of John Rogers, in the materials science and engineering department.

“Most preclinical strategies have relied on direct injections into the heart, but because this is not a feasible option for humans, we sought to develop a platform that could be delivered via intracoronary or transendocardial catheter,” says Carlini, who was a graduate student in Gianneschi’s lab when the researchers conducted the study.

Peptides are short chains of amino acids instrumental for healing. The team’s approach relies on a catheter to deliver self-assembling peptides—and eventually a therapeutic—to the heart following myocardial infarction, or heart attack.

“What we’ve created is a targeting-and-response type of material,” says Gianneschi, associate director of Northwestern’s International Institute of Nanotechnology and a member of the Simpson Querrey Institute.

“We inject a self-assembling peptide solution that seeks out a target—the heart’s damaged extracellular matrix—and the solution is then activated by the inflammatory environment itself and gels,” he says.

“The key is to have the material create a self-assembling framework, which mimics the natural scaffold that holds cells and tissues together.”

Proving the concept

The team conducted their preclinical research in rats and segmented the work into two proof-of-concept tests.

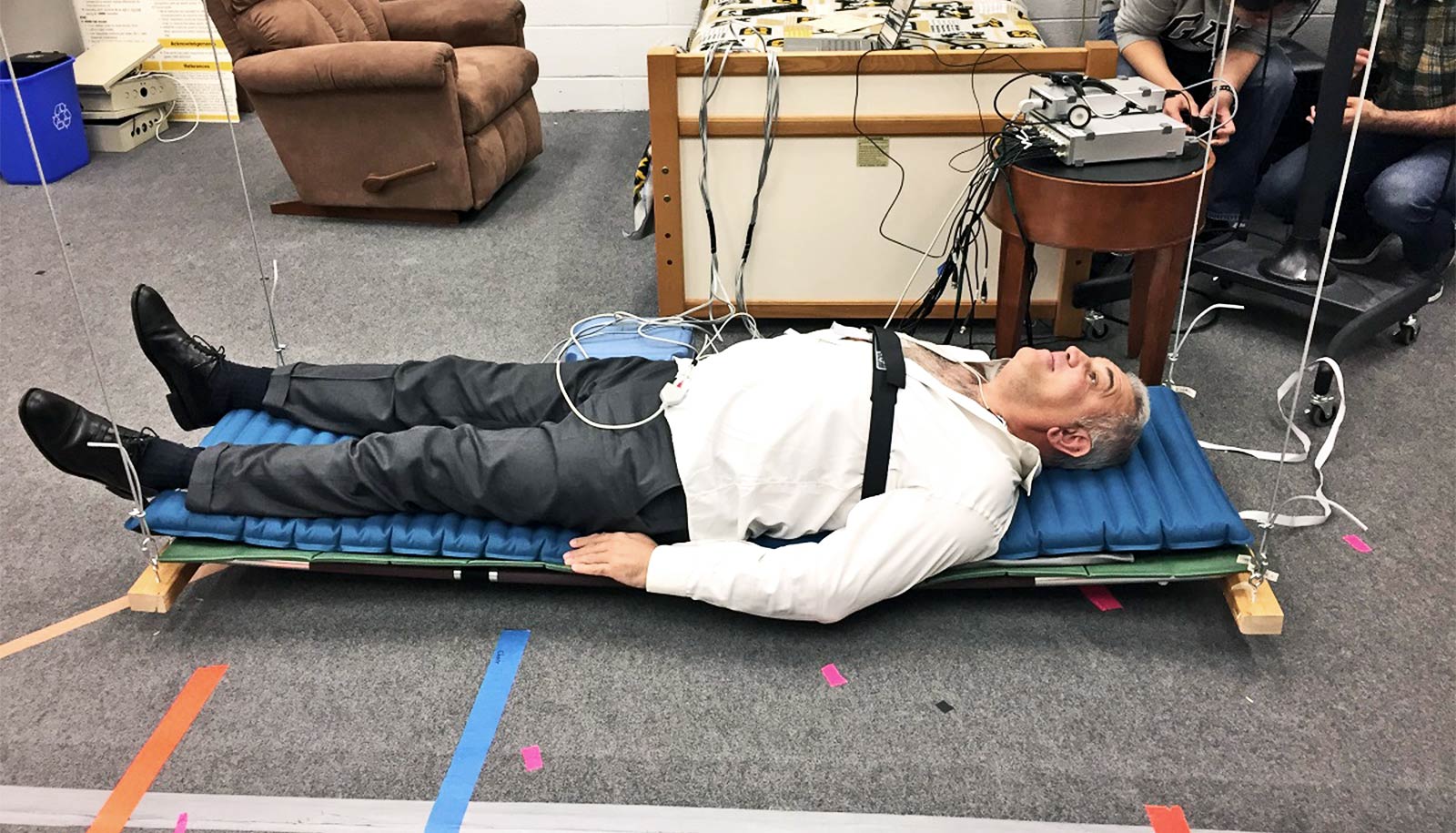

The first test established that they could feed the material through a catheter without clogging and without interacting with human blood. The second determined whether the self-assembling peptides could find their way to the damaged tissue, bypassing healthy heart tissue. Researchers created and attached a fluorescent tag to the self-assembling peptides and then imaged the heart to see where the peptides eventually settled.

“In previous work with responsive nanoparticles, we produced speckled fluorescence in the heart attack region, but in this case, we were able to see large continuous hydrogel assemblies throughout the tissue,” Carlini says.

Researchers now know that when they remove the florescent tag and replace it with a therapeutic, the self-assembling peptides will locate to the affected area of the heart. One hurdle is that catheter delivery in a rodent model is far more complicated—because of the animal’s much smaller body—than the same procedure in a human.

If the research team can prove their approach to be efficacious, then there is “a fairly clear path” in terms of progressing toward a clinical trial, Gianneschi says. The process, however, would take several years.

“We started working on this chemistry in 2012, and it took immense effort to produce a modular and synthetically simple platform that would reliably gel in response to the inflammatory environment,” Carlini says.

“A major breakthrough occurred when we developed sterically constrained cyclic peptides, which flow freely during delivery and then rapidly assemble into hydrogels when they come in contact with disease-associated enzymes.”

By programming in a spring-like switch, Carlini was able to unfurl these naturally circular compounds to create a flat substance with much more surface area and greater stickiness. The process creates conditions for the peptides to better self-assemble, or stack, atop one another and form the scaffold that so closely resembles the native extracellular matrix.

Having demonstrated the platform’s ability to activate in the presence of specific disease-associated enzymes, Gianneschi’s lab also has validated analogous approaches in peripheral artery disease and in metastatic cancer, each of which produce similar chemical and biological inflammatory responses.

The National Institutes of Health Director’s Transformative Research Award; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and an Air Force Office of Scientific Research MURI funded the study. Karen Christman from the University of California, San Diego’s contributed to the work.

Source: Northwestern University