Administrative “sludge” in health insurance costs employers and the economy billions of dollars in squandered work time, employee stress, absenteeism, and reduced productivity, according to a new study.

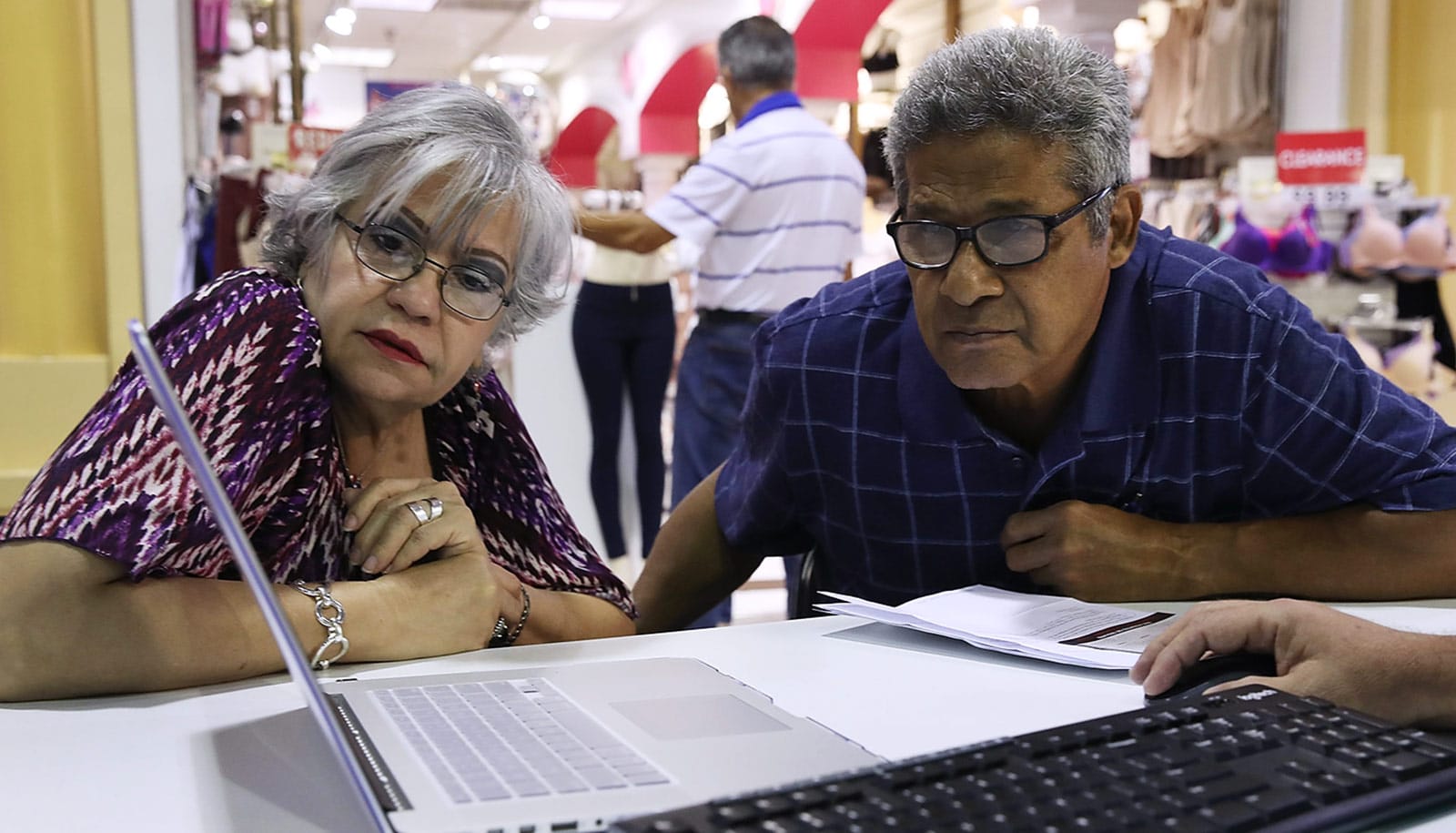

It seems everybody has a horror story about health insurance: Kafkaesque debates with robotic agents about what is and isn’t covered. Huge bills from a doctor you didn’t know was “out of network.” Reimbursements that take months to process.

It’s no secret that health care in the United States is tangled in wasteful red tape. A study in 2019 estimated that administrative complexity was the single biggest source of waste in health care—bigger even than fraud or over-pricing—and imposes an annual cost of $265 billion.

The new study shows that the true extent of that waste is even more shocking.

Specifically, researchers estimate, the economy loses $21.6 billion a year simply from the time employees spend on the phone with health insurance representatives. On top of that, the study estimates that companies lose $26 billion a year from extra absence on the part of employees who have to deal with health benefits administrators, and $95 billion from the reduced productivity that arises because people who spend time on the phone with health insurers are less satisfied with their jobs.

If employers held benefits administrators accountable for reducing administrative hassles in the system, it could diminish all of those dead-weight losses to the economy.

‘Simple arithmetic’

Jeffrey Pfeffer of the Stanford Graduate School of Business, lead author of the paper in Academy of Management Discoveries, teamed up with researchers at Gallup, the polling company, to assess how much time employees spend on the phone with benefit administrators and how those encounters affect their work.

“Until now, most of the research on health care sludge has focused on the paperwork costs incurred by health care providers such as doctors and hospitals,” Pfeffer says. “Our new twist, which I can’t believe no one looked at before, is how much employee time is wasted and the measurable effect of that time on employee stress, burnout, increased absence, and diminished job satisfaction.”

“If you don’t hold health insurers accountable, you shouldn’t expect them to do a particularly good job—and they don’t.”

To begin, the team polled people on how much time they had spent on the phone in the prior week with health insurance administrators. The researchers used data collected from surveys of the Gallup Panel, a 100,000-member group formed in 2004 and designed to represent the entire US adult population. The surveys used in this study had a sample size of about 6,200 people.

There are weeks, of course, when people don’t talk to their health insurers at all. But on average, the respondents reported spending almost three minutes of working time and 5.5 minutes in total during the prior week on such calls.

Extrapolating that to some 130 million full-time workers in the US, at an average cost per worker of $37 per hour, those phone calls added up to a nationwide cost of $414 million per week in lost work time. Part-time employees contributed another $50 million in lost work per week. All told, the annual cost of lost work amounted to $21 billion—frittered away while talking on the phone with health insurance representatives.

“It’s simple arithmetic,” Pfeffer says.

Health insurance frustration

As a next step, the team looked at whether those encounters made people more dissatisfied and less engaged in their work.

Sure enough, the people who had talked with a benefits administrator were significantly less satisfied with their jobs and more likely to be absent from work.

Even when the researchers controlled for people’s self-reported health, those who had talked with a benefits person the previous week were 10% less likely to be satisfied with their workplace and 14% less likely to feel engaged.

They were also more likely to make their companies pay for their discontent: Employees who had talked with a benefits administrator were 35% more likely to be absent a day or more from work, amounting to a nationwide annual cost of $26 billion.

Drawing on extensive research about the link between workers’ job satisfaction and productivity, Pfeffer and colleagues estimate that the reduced job satisfaction coming from spending time on the phone with health insurers costs the country an additional $95 billion annually in reduced productivity.

Pfeffer acknowledges that he plunged into the issue because of his own frustration with Blue Shield of California, an experience he writes about in his forthcoming book, I’ve Got the Blues: What a Year with California Blue Shield Taught Me About What’s Wrong with America’s Employer-Sponsored Health Care—and How to Fix It.

Who should we blame?

Pfeffer says the fault lies less with insurance companies than with the companies that hire them and then fail to hold them accountable.

“CEOs are the ones who should care about this, but they’re only interested in how to reduce direct medical costs,” he says, “not realizing that the indirect costs of turnover, absenteeism, and diminished productivity are many times the direct costs of ill-health.

“We don’t hold these outside administrators accountable. We don’t measure how long it takes them to process claims, or how much aggravation they’re causing employees, or whether they are in fact helping with recruitment and retention through their actions. If you don’t hold health insurers accountable, you shouldn’t expect them to do a particularly good job—and they don’t.”

The upshot, Pfeffer continues, is that companies end up paying huge sums of money for employee health care benefits that don’t provide increased employee morale because of the burdens imposed by insurers.

“Companies say they offer health insurance to attract and retain talent, but they’re offering a benefit which is administered so that it often doesn’t feel like a benefit,” says Pfeffer. “If employers would select better-performing health insurers and get rid of those that are administratively inefficient, they would get more value for the money they are spending.”

Additional coauthors are from Gallup’s National Health and Well-Being Index.

Source: Stanford University