Haze affects the survival and development of butterflies, report biologists.

The burning of regional peat forests to clear land for agriculture causes a large-scale air pollution issue called the Southeast Asia (SEA) transboundary haze.

Apart from causing economic losses for countries in this region, the haze is also hazardous to human health. The smoke causing the haze contains harmful gases (e.g. carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and sulphur dioxide) and tiny particles. Although there are studies on the impact of haze on human well-being, the effect on other species and our ecosystems is less clear.

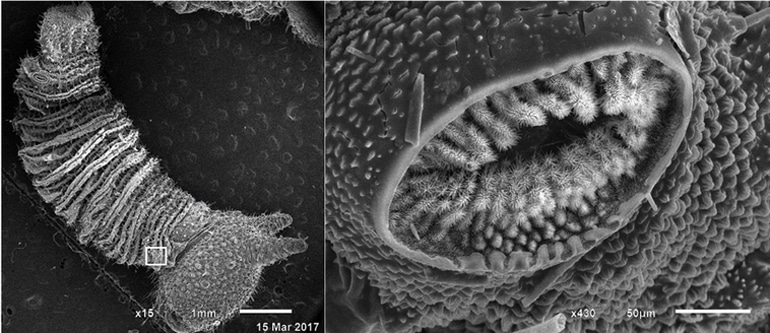

Insects are very sensitive to changes in air quality because the air reaches cells inside their body in a very direct way. Insects breathe via spiracles, which are valve-like openings on the side of their bodies. These openings connect to internal tracheal tubes that branch repeatedly into finer tracheoles and eventually reach every cell inside the insect’s body, where diffusion of gases occurs. This is not the case in our own bodies, where the air first diffuses into the blood system in our lungs before reaching cells.

Professor Antónia Monteiro from the department of biological sciences at NUS led the team that discovered that smoke-induced toxicity to the environment and toxic chemicals in haze resulted in a higher larval mortality and slower development in the caterpillars of the squinting bush brown butterfly (Bicyclus anynana).

While this species lives naturally in Africa, relatives of this butterfly, from the genus Mycalesis, are common in Singapore and in many forests of SEA. The experiments took place in a controlled laboratory setting using artificially generated smoke from burning incense coils.

The researchers found at least two effects on the caterpillars. First, a large proportion of individual caterpillars did not survive before they could reach their adult stage due to the toxic chemicals in the smoke. Second, the smoke reduced the available food sources to the surviving caterpillars, either by damaging the plant they ate, or by preventing the caterpillars from locating it.

Those individuals that developed in the smoke treatment took longer to reach the adult stage and turned into smaller adults than the caterpillars which developed in a cleaner air environment (simulating the air quality in SEA without haze), and thus were likely to suffer from reduced potential for reproduction.

Emilie Dion, a postdoctoral fellow on the team, says, “This study is only the first step in understanding the impact of smoke on a population of insects. In the natural environment, the haze may affect multiple members of a complex food web, which includes their predators and this may lead to a less predictable outcome.”

“Our findings provide an insight into the adverse effects of haze smoke on butterflies, which are sensitive to environmental disturbances,” adds Monteiro. “As they are easy to identify and monitor, butterflies could be useful as bioindicators of the health of an ecosystem for better haze management in the SEA region and other important biodiversity hotspots on our planet.”

The research appears in Scientific Reports.

Source: National University of Singapore